Using FiPy¶

This document explains how to use FiPy in a practical sense. To see the problems that FiPy is capable of solving, you can run any of the scripts in the examples.

Note

We strongly recommend you proceed through the examples, but at the very least work through

examples.diffusion.mesh1D to understand the notation and

basic concepts of FiPy.

We exclusively use either the UNIX command line or IPython to interact with FiPy. The commands in the examples are written with the assumption that they will be executed from the command line. For instance, from within the main FiPy directory, you can type:

$ python examples/diffusion/mesh1D.py

A viewer should appear and you should be prompted through a series of examples.

In order to customize the examples, or to develop your own scripts, some knowledge of Python syntax is required. We recommend you familiarize yourself with the excellent Python tutorial [10] or with Dive Into Python [11]. Deeper insight into Python can be obtained from the [12].

As you gain experience, you may want to browse through the Command-line Flags and Environment Variables that affect FiPy.

Logging¶

Diagnostic information about a FiPy run can be obtained using the

logging module. For example, at the beginning of your script, you

can add:

>>> import logging

>>> log = logging.getLogger("fipy")

>>> console = logging.StreamHandler()

>>> console.setLevel(logging.INFO)

>>> log.addHandler(console)

in order to see informational messages in the terminal. To have more verbose debugging information save to a file:

>>> logfile = logging.FileHandler(filename="fipy.log")

>>> logfile.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

>>> log.addHandler(logfile)

>>> log.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

To restrict logging to, e.g., information about the PETSc solvers:

>>> petsc = logging.Filter('fipy.solvers.petsc')

>>> logfile.addFilter(petsc)

More complex configurations can be specified by setting the

FIPY_LOG_CONFIG environment variable. In this case, it is not

necessary to add any logging instructions to your own script. Example

configuration files can be found in

FiPySource/fipy/tools/logging/.

If Solving in Parallel, the mpilogging package enables reporting which MPI rank each log entry comes from. For example:

>>> from mpilogging import MPIScatteredFileHandler

>>> mpilog = MPIScatteredFileHandler(filepattern="fipy.%(mpirank)d_of_%(mpisize)d.log"

>>> mpilog.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

>>> log.addHandler(mpilog)

will generate a unique log file for each MPI rank.

Testing FiPy¶

For a general installation, FiPy can be tested by running:

$ python -c "import fipy; fipy.test()"

This command runs all the test cases in FiPy’s modules, but doesn’t include any of the tests in FiPy’s examples. To run the test cases in both modules and examples, use:

$ fipy_test

Note

You may need to first run:

$ python -m build

for this to work properly.

in an unpacked FiPy archive. The test suite can be run with a number of different configurations depending on which solver suite is available and other factors. See Command-line Flags and Environment Variables for more details.

FiPy will skip tests that depend on Optional Packages that have not been installed. For example, if Mayavi and Gmsh are not installed, FiPy will warn something like:

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Skipped 131 doctest examples because `gmsh` cannot be found on the $PATH

Skipped 42 doctest examples because the `tvtk` package cannot be imported

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Although the test suite may show warnings, there should be no other errors. Any errors should be investigated or reported on the issue tracker. Users can see if there are any known problems for the latest FiPy distribution by checking FiPy’s Continuous Integration dashboard.

Below are a number of common Command-line Flags for testing various FiPy configurations.

Parallel Tests¶

If FiPy is configured for Solving in Parallel, you can run the tests on multiple processor cores with:

$ mpirun -np {# of processors} fipy_test --trilinos

or:

$ mpirun -np {# of processors} python -c "import fipy; fipy.test('--trilinos')"

Command-line Flags and Environment Variables¶

FiPy chooses a default run time configuration based on the available packages on the system. The Command-line Flags and Environment Variables sections below describe how to override FiPy’s default behavior.

Command-line Flags¶

You can add any of the following case-insensitive flags after the name of a script you call from the command line, e.g.:

$ python myFiPyScript --someflag

- --inline¶

Causes many mathematical operations to be performed in C, rather than Python, for improved performance. Requires the

weavepackage.

The following flags take precedence over the FIPY_SOLVERS

environment variable:

- --skfmm¶

Forces the use of the Scikit-fmm level set solver.

Environment Variables¶

You can set any of the following environment variables in the manner

appropriate for your shell. If you are not running in a shell (e.g.,

you are invoking FiPy scripts from within IPython or IDLE),

you can set these variables via the os.environ dictionary,

but you must do so before importing anything from the fipy

package.

- FIPY_DISPLAY_MATRIX¶

If present, causes the graphical display of the solution matrix of each equation at each call of

solve()orsweep(). Setting the value to “terms” causes the display of the matrix for eachTermthat composes the equation. Requires the Matplotlib package. Setting the value to “print” causes the matrix to be printed to the console.

- FIPY_INLINE¶

If present, causes many mathematical operations to be performed in C, rather than Python. Requires the

weavepackage.

- FIPY_INLINE_COMMENT¶

If present, causes the addition of a comment showing the Python context that produced a particular piece of

weaveC code. Useful for debugging.

- FIPY_LOG_CONFIG¶

Specifies a JSON-formatted logging configuration file, suitable for passing to

logging.config.dictConfig(). Example configuration files can be found inFiPySource/fipy/tools/logging/.

- FIPY_SOLVERS¶

Forces the use of the specified suite of linear Solvers. Valid (case-insensitive) choices are “

petsc”, “pyamgx”, “scipy”, and “trilinos”.

- FIPY_DEFAULT_CRITERION¶

Changes the default solver Convergence criterion to the specified value. Valid choices are “

legacy”, “unscaled”, “RHS”, “matrix”, “initial”, “solution”, “preconditioned”, “natural”, “default”. A value of “default” is admittedly circular, but it works.

- FIPY_VIEWER¶

Forces the use of the specified viewer. Valid values are any

<viewer>from thefipy.viewers.<viewer>Viewermodules. The special value ofdummywill allow the script to run without displaying anything.

- FIPY_INCLUDE_NUMERIX_ALL¶

If present, causes the inclusion of all functions and variables of the

numerixmodule in thefipynamespace.

- PETSC_OPTIONS¶

PETSc configuration options. Set to “-help” and run a script with PETSc solvers in order to see what options are possible. Ignored if solver is not PETSc.

Solver Suites¶

Numerical solution of partial differential equations calls for solving sparse linear algebra. FiPy supports several different Solvers. To the greatest extent possible, they have all been configured to do the “same thing”, but each presents different capabilities in terms of matrix preconditioning and overall performance tuning.

Solving in Parallel¶

FiPy can use PETSc or Trilinos to solve equations in

parallel. Most mesh classes in fipy.meshes can solve in

parallel. This includes all “...Grid...” and “...Gmsh...”

class meshes. Currently, the only remaining serial-only meshes are

Tri2D and

SkewedGrid2D.

Tip

You are strongly advised to force the use of only one OpenMP thread with PETSc and Trilinos:

$ export OMP_NUM_THREADS=1

See OpenMP Threads vs. MPI Ranks for more information.

It should not generally be necessary to change anything in your script. Simply invoke:

$ mpirun -np {# of processors} python myScript.py --petsc

or:

$ FIPY_SOLVERS=trilinos mpirun -np {# of processors} python myScript.py

instead of:

$ python myScript.py

The easiest way to confirm that FiPy is properly configured to solve in parallel is to run one of the examples, e.g.,:

$ mpirun -np 2 examples/diffusion/mesh1D.py

You should see two viewers open with half the simulation running in one of them and half in the other. If this does not look right (e.g., you get two viewers, both showing the entire simulation), or if you just want to be sure, you can run a diagnostic script:

$ mpirun -np 3 python examples/parallel.py

which should print out:

mpi4py PyTrilinos petsc4py FiPy

processor 0 of 3 :: processor 0 of 3 :: processor 0 of 3 :: 5 cells on processor 0 of 3

processor 1 of 3 :: processor 1 of 3 :: processor 1 of 3 :: 7 cells on processor 1 of 3

processor 2 of 3 :: processor 2 of 3 :: processor 2 of 3 :: 6 cells on processor 2 of 3

If there is a problem with your parallel environment, it should be clear that there is either a problem importing one of the required packages or that there is some problem with the MPI environment. For example:

mpi4py PyTrilinos petsc4py FiPy

processor 0 of 3 :: processor 0 of 1 :: processor 0 of 3 :: 10 cells on processor 0 of 1

[my.machine.com:69815] WARNING: There were 4 Windows created but not freed.

processor 1 of 3 :: processor 0 of 1 :: processor 1 of 3 :: 10 cells on processor 0 of 1

[my.machine.com:69814] WARNING: There were 4 Windows created but not freed.

processor 2 of 3 :: processor 0 of 1 :: processor 2 of 3 :: 10 cells on processor 0 of 1

[my.machine.com:69813] WARNING: There were 4 Windows created but not freed.

indicates mpi4py is properly communicating with MPI and is running in parallel, but that Trilinos is not, and is running three separate serial environments. As a result, FiPy is limited to three separate serial operations, too. In this instance, the problem is that although Trilinos was compiled with MPI enabled, it was compiled against a different MPI library than is currently available (and which mpi4py was compiled against). The solution, in this instance, is to solve with PETSc or to rebuild Trilinos against the active MPI libraries.

When solving in parallel, FiPy essentially breaks the problem

up into separate sub-domains and solves them (somewhat) independently.

FiPy generally “does the right thing”, but if you find that

you need to do something with the entire solution, you can use

var.globalValue.

Note

One option for debugging in parallel is:

$ mpirun -np {# of processors} xterm -hold -e "python -m ipdb myScript.py"

OpenMP Threads vs. MPI Ranks¶

By default, PETSc and Trilinos spawn as many OpenMP threads as there are cores available. This may very well be an intentional optimization, where they are designed to have one MPI rank per node of a cluster, so each of the child threads would help with computation but would not compete for I/O resources during ghost cell exchanges and file I/O. However, Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) binds all of the child threads to the same core as their parent! So instead of improving performance, each core suffers a heavy overhead from managing those idling threads.

The solution to this is to force these solvers to use only one OpenMP thread:

$ export OMP_NUM_THREADS=1

Because this environment variable affects all processes launched in the current session, you may prefer to restrict its use to FiPy runs:

$ OMP_NUM_THREADS=1 mpirun -np {# of processors} python myScript.py --trilinos

The difference can be extreme. We have observed the FiPy test

suite to run in just over two minutes when OMP_NUM_THREADS=1,

compared to over an hour and 23 minutes when OpenMP threads are

unrestricted.

This issue is not limited to FiPy or the parallel solver suites it

uses; see

Can There Be Too Much Parallelism?

for a deeper look at the different threading settings available and their

effects.

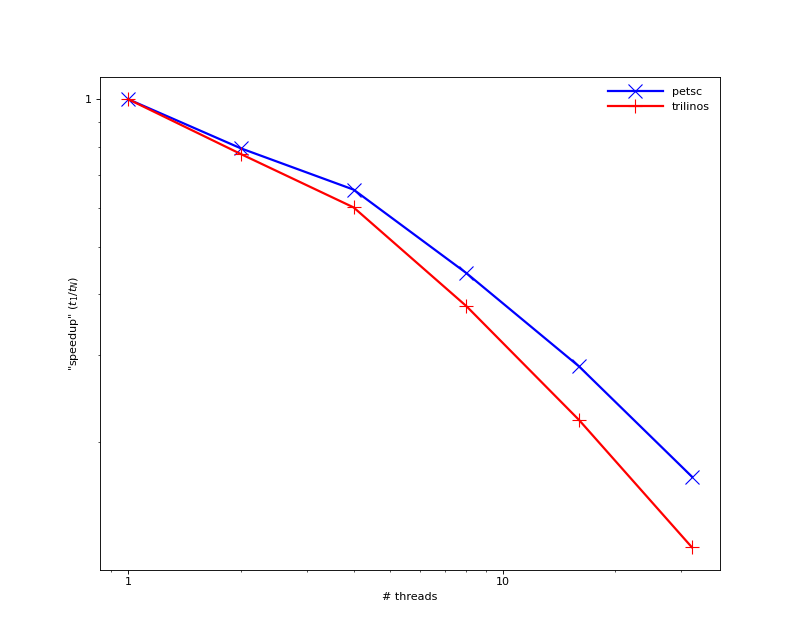

Conceivably, allowing these parallel solvers unfettered access to OpenMP threads with no MPI communication at all could perform as well or better than purely MPI parallelization. The plot below demonstrates this is not the case. We compare solution time vs number of OpenMP threads for fixed number of slots for a Method of Manufactured Solutions Allen-Cahn problem (OpenMP threads \(\times\) MPI ranks = Slurm tasks). OpenMP threading always slows down FiPy performance.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Effect of having more OpenMP threads for each MPI rank [1].¶

See https://www.mail-archive.com/fipy@nist.gov/msg03393.html for further analysis.

It may be possible to configure these packages to use only one OpenMP thread, but this is not the configuration of the version available from conda-forge and building Trilinos, at least, is NotFun™.

Meshing with Gmsh¶

FiPy works with arbitrary polygonal meshes generated by

Gmsh. FiPy provides two wrappers classes

(Gmsh2D and

Gmsh3D) enabling Gmsh to be

used directly from python. The classes can be instantiated with a set

of Gmsh style commands (see

examples.diffusion.circle). The classes can also be

instantiated with the path to either a Gmsh geometry file

(.geo) or a Gmsh mesh file (.msh) (see

examples.diffusion.anisotropy).

As well as meshing arbitrary geometries, Gmsh partitions

meshes for parallel simulations. Mesh partitioning automatically

occurs whenever a parallel communicator is passed to the mesh on

instantiation. This is the default setting for all meshes that work in

parallel including Gmsh2D and

Gmsh3D.

Note

FiPy solution accuracy can be compromised with highly non-orthogonal or non-conjunctional meshes.

Coupled and Vector Equations¶

Equations can now be coupled together so that the contributions from

all the equations appear in a single system matrix. This results in

tighter coupling for equations with spatial and temporal derivatives

in more than one variable. In FiPy equations are coupled

together using the & operator:

>>> eqn0 = ...

>>> eqn1 = ...

>>> coupledEqn = eqn0 & eqn1

The coupledEqn will use a combined system matrix that includes

four quadrants for each of the different variable and equation

combinations. In previous versions of FiPy there has been no

need to specify which variable a given term acts on when generating

equations. The variable is simply specified when calling solve or

sweep and this functionality has been maintained in the case of

single equations. However, for coupled equations the variable that a

given term operates on now needs to be specified when the equation is

generated. The syntax for generating coupled equations has the form:

>>> eqn0 = Term00(coeff=..., var=var0) + Term01(coeff..., var=var1) == source0

>>> eqn1 = Term10(coeff=..., var=var0) + Term11(coeff..., var=var1) == source1

>>> coupledEqn = eqn0 & eqn1

and there is now no need to pass any variables when solving:

>>> coupledEqn.solve(dt=..., solver=...)

In this case the matrix system will have the form

FiPy tries to make sensible decisions regarding each term’s

location in the matrix and the ordering of the variable column

array. For example, if Term01 is a transient term then Term01

would appear in the upper left diagonal and the ordering of the

variable column array would be reversed.

The use of coupled equations is described in detail in

examples.diffusion.coupled. Other examples that demonstrate the

use of coupled equations are examples.phase.binaryCoupled,

examples.phase.polyxtalCoupled and

examples.cahnHilliard.mesh2DCoupled. As well as coupling

equations, true vector equations can now be written in FiPy.

Attention

Coupled equations are not compatible with Higher Order Diffusion terms. This is not a practical limitation, as any higher order terms can be decomposed into multiple 2nd-order equations. For example, the pair of coupled Cahn-Hilliard & Allen-Cahn 4th- and 2nd-order equations

can be decomposed to three 2nd-order equations

Boundary Conditions¶

Default boundary conditions¶

If no constraints are applied, solutions are conservative, i.e., all boundaries are zero flux. For the equation

the condition on the boundary \(S\) is

Applying fixed value (Dirichlet) boundary conditions¶

To apply a fixed value boundary condition use the

constrain() method. For example, to fix var to

have a value of 2 along the upper surface of a domain, use

>>> var.constrain(2., where=mesh.facesTop)

Note

The old equivalent

FixedValue boundary

condition is now deprecated.

Applying fixed gradient boundary conditions (Neumann)¶

To apply a fixed Gradient boundary condition use the

faceGrad.constrain() method. For

example, to fix var to have a gradient of (0,2) along the upper

surface of a 2D domain, use

>>> var.faceGrad.constrain(((0,),(2,)), where=mesh.facesTop)

If the gradient normal to the boundary (e.g., \(\hat{n}\cdot\nabla\phi\)) is to be set to a scalar value of 2, use

>>> var.faceGrad.constrain(2 * mesh.faceNormals, where=mesh.exteriorFaces)

Applying fixed flux boundary conditions¶

Generally these can be implemented with a judicious use of

faceGrad.constrain(). Failing that, an

exterior flux term can be added to the equation. Firstly, set the

terms’ coefficients to be zero on the exterior faces,

>>> diffCoeff.constrain(0., mesh.exteriorFaces)

>>> convCoeff.constrain(0., mesh.exteriorFaces)

then create an equation with an extra term to account for the exterior flux,

>>> eqn = (TransientTerm() + ConvectionTerm(convCoeff)

... == DiffusionCoeff(diffCoeff)

... + (mesh.exteriorFaces * exteriorFlux).divergence)

where exteriorFlux is a rank 1

FaceVariable.

Note

The old equivalent FixedFlux

boundary condition is now deprecated.

Applying outlet or inlet boundary conditions¶

Convection terms default to a no flux boundary condition unless the exterior faces are associated with a constraint, in which case either an inlet or an outlet boundary condition is applied depending on the flow direction.

Applying spatially varying boundary conditions¶

The use of spatial varying boundary conditions is best demonstrated with an example. Given a 2D equation in the domain \(0 < x < 1\) and \(0 < y < 1\) with boundary conditions,

where \(\vec{F}\) represents the flux. The boundary conditions in FiPy can be written with the following code,

>>> X, Y = mesh.faceCenters

>>> mask = ((X < 0.5) | (Y < 0.5))

>>> var.faceGrad.constrain(0, where=mesh.exteriorFaces & mask)

>>> var.constrain(X * Y, where=mesh.exteriorFaces & ~mask)

then

>>> eqn.solve(...)

Further demonstrations of spatially varying boundary condition can be found

in examples.diffusion.mesh20x20

and examples.diffusion.circle

Applying Robin boundary conditions¶

The Robin condition applied on the portion of the boundary \(S_R\)

can often be substituted for the flux in an equation

At faces identified by mask,

>>> a = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=1)

>>> a.setValue(0., where=mask)

>>> b = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=0)

>>> b.setValue(0., where=mask)

>>> g = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=0)

>>> eqn = (TransientTerm() == PowerLawConvectionTerm(coeff=a)

... + DiffusionTerm(coeff=b)

... + (g * mask * mesh.faceNormals).divergence)

When the Robin condition does not exactly map onto the boundary flux, we can attempt to apply it term by term. The Robin condition relates the gradient at a boundary face to the value on that face, however FiPy naturally calculates variable values at cell centers and gradients at intervening faces. Using a first order upwind approximation, the boundary value of the variable at face \(f\) can be written in terms of the value at the neighboring cell \(P\) and the normal gradient at the boundary:

where \(\vec{d}_{Pf}\) is the distance vector to the center of the face \(f\) from the center of the adjoining cell \(P\). The approximation \(\left(\vec{d}_{Pf}\cdot\nabla\phi\right)_f \approx \left(\hat{n}\cdot\nabla\phi\right)_f\left(\vec{d}_{Pf}\cdot\hat{n}\right)_f\) is most valid when the mesh is orthogonal.

Substituting this expression into the Robin condition:

we obtain an expression for the gradient at the boundary face in terms of its neighboring cell. We can, in turn, substitute this back into (1)

to obtain the value on the boundary face in terms of the neighboring cell.

Substituting (2) into the discretization of the

DiffusionTerm:

An equation of the form

>>> eqn = TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm(coeff=Gamma0)

can be constrained to have a Robin condition at faces identified by

mask by making the following modifications

>>> Gamma = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=Gamma0)

>>> Gamma.setValue(0., where=mask)

>>> dPf = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh,

... value=mesh._faceToCellDistanceRatio * mesh.cellDistanceVectors)

>>> n = mesh.faceNormals

>>> a = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=1)

>>> b = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=0)

>>> g = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=..., rank=0)

>>> RobinCoeff = mask * Gamma0 * n / (dPf.dot(a) + b)

>>> eqn = (TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm(coeff=Gamma) + (RobinCoeff * g).divergence

... - ImplicitSourceTerm(coeff=(RobinCoeff * n.dot(a)).divergence)

Similarly, for a ConvectionTerm, we can

substitute (3):

Note

An expression like the heat flux convection boundary condition \(-k\nabla T\cdot\hat{n} = h(T - T_\infty)\) can be put in the form of the Robin condition used above by letting \(\vec{a} \equiv h \hat{n}\), \(b \equiv k\), and \(g \equiv h T_\infty\).

Applying internal “boundary” conditions¶

Applying internal boundary conditions can be achieved through the use of implicit and explicit sources.

Internal fixed value¶

An equation of the form

>>> eqn = TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm()

can be constrained to have a fixed internal value at a position

given by mask with the following alterations

>>> eqn = (TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm()

... - ImplicitSourceTerm(mask * largeValue)

... + mask * largeValue * value)

The parameter largeValue must be chosen to be large enough to

completely dominate the matrix diagonal and the RHS vector in cells

that are masked. The mask variable would typically be a

CellVariable Boolean constructed using the cell center values.

Internal fixed gradient¶

An equation of the form

>>> eqn = TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm(coeff=Gamma0)

can be constrained to have a fixed internal gradient magnitude

at a position given by mask with the following alterations

>>> Gamma = FaceVariable(mesh=mesh, value=Gamma0)

>>> Gamma[mask.value] = 0.

>>> eqn = (TransientTerm() == DiffusionTerm(coeff=Gamma)

... + DiffusionTerm(coeff=largeValue * mask)

... - ImplicitSourceTerm(mask * largeValue * gradient

... * mesh.faceNormals).divergence)

The parameter largeValue must be chosen to be large enough to

completely dominate the matrix diagonal and the RHS vector in cells

that are masked. The mask variable would typically be a

FaceVariable Boolean constructed using the face center values.

Internal Robin condition¶

Nothing different needs to be done when applying Robin boundary conditions at internal faces.

Note

While we believe the derivations for applying Robin boundary conditions are “correct”, they often do not seem to produce the intuitive result. At this point, we think this has to do with the pathology of “internal” boundary conditions, but remain open to other explanations. FiPy was designed with diffuse interface treatments (phase field and level set) in mind and, as such, internal “boundaries” do not come up in our own work and have not received much attention.

Warning

The constraints mechanism is not designed to constrain internal values

for variables that are being solved by equations. In particular, one must

be careful to distinguish between constraining internal cell values

during the solve step and simply applying arbitrary constraints to a

CellVariable. Applying a constraint,

>>> var.constrain(value, where=mask)

simply fixes the returned value of var at mask to be

value. It does not have any effect on the implicit value of var at the

mask location during the linear solve so it is not a substitute

for the source term machinations described above. Future releases of

FiPy may implicitly deal with this discrepancy, but the current

release does not.

A simple example can be used to demonstrate this:

>>> m = Grid1D(nx=2, dx=1.)

>>> var = CellVariable(mesh=m)

We wish to solve \(\nabla^2 \phi = 0\) subject to \(\phi\rvert_\text{right} = 1\) and \(\phi\rvert_{x < 1} = 0.25\). We apply a constraint to the faces for the right side boundary condition (which works).

>>> var.constrain(1., where=m.facesRight)

We create the equation with the source term constraint described above

>>> mask = m.x < 1.

>>> largeValue = 1e+10

>>> value = 0.25

>>> eqn = DiffusionTerm() - ImplicitSourceTerm(largeValue * mask) + largeValue * mask * value

and the expected value is obtained.

>>> eqn.solve(var)

>>> print var

[ 0.25 0.75]

However, if a constraint is used without the source term constraint an unexpected solution is obtained

>>> var.constrain(0.25, where=mask)

>>> eqn = DiffusionTerm()

>>> eqn.solve(var)

>>> print var

[ 0.25 1. ]

although the left cell has the expected value as it is constrained.

FiPy has simply solved \(\nabla^2 \phi = 0\) with \(\phi\rvert_\text{right} = 1\) and (by default) \(\hat{n}\cdot\nabla\phi\rvert_\text{left} = 0\), giving \(\phi = 1\) everywhere, and then subsequently replaced the cells \(x < 1\) with \(\phi = 0.25\).

Adaptive Stepping¶

Step size can be controlled with the steppyngstounes package.

Demonstrations of its use are found in examples.phase.binary and

examples.phase.binaryCoupled.

Note

The old fipy.steppers classes are now deprecated. They were

undocumented and did not work very well.

Manual¶

You can view the manual online at <http://pages.nist.gov/fipy> (a PDF

version is available from the variant popup menu in the bottom right of

those documentation pages).

Alternatively, it may be possible to build a fresh copy by issuing the

following command in the docs/ directory:

$ make html

or:

$ make latexpdf

Note

This mechanism is intended primarily for the developers. At a minimum, you will need Sphinx, plus all of its prerequisites. We are currently building with Sphinx v7.0.

We install via conda:

$ conda install --channel conda-forge sphinx

Bibliographic citations require the sphinxcontrib-bibtex package:

$ python -m pip install sphinxcontrib-bibtex

Some documentation uses numpydoc styling:

$ python -m pip install numpydoc

Some embeded figures require matplotlib, pandas, and imagemagick:

$ conda install --channel conda-forge matplotlib pandas imagemagick

The PDF file requires SIunits.sty available, e.g., from texlive-science.

Spelling is checked automatically in the course of Continuous Integration. If you wish to check manually, you will need pyspelling, hunspell, and the libreoffice dictionaries:

$ conda install --channel conda-forge hunspell

$ python -m pip install pyspelling

$ wget -O en_US.aff https://cgit.freedesktop.org/libreoffice/dictionaries/plain/en/en_US.aff?id=a4473e06b56bfe35187e302754f6baaa8d75e54f

$ wget -O en_US.dic https://cgit.freedesktop.org/libreoffice/dictionaries/plain/en/en_US.dic?id=a4473e06b56bfe35187e302754f6baaa8d75e54f

FiPy

FiPy