Tue, 26 Aug 2025 08:51:12 -0500

ABSTRACT

These guidelines cover the identity proofing, authentication, and federation of users (e.g., employees, contractors, or private individuals) who interact with government information systems over networks. They define technical requirements in each of the areas of identity proofing, enrollment, authenticators, management processes, authentication protocols, federation, and related assertions. They also offer technical recommendations and other informative text as helpful suggestions. The guidelines are not intended to constrain the development or use of standards outside of this purpose. This publication supersedes NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-63-3.

Keywords

assertions; authentication; authentication assurance; authenticator; credential service provider; digital authentication; identity proofing; federation; passwords; PKI.

Preface

This publication and its companion volumes — [SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], and [SP800-63C] — provide technical and process guidelines to organizations for the implementation of digital identity services.

Introduction

This section is informative.

The rapid proliferation of online services over the past few years has heightened the need for reliable, secure, and privacy-protective digital identity solutions. A digital identity is always unique in the context of an online service. However, a person could have multiple digital identities and, while a digital identity could relay a unique and specific meaning within the context of an online service, the real-life identity of the individual behind the digital identity might not be known. When confidence in a person’s real-life identity is not required to provide access to an online service, organizations can use anonymous or pseudonymous accounts. In all other use cases, a digital identity is intended to establish trust between the holder of the digital identity and the person, organization, or system interacting with the online service. However, this process can present challenges. There are multiple opportunities for mistakes, miscommunication, and attacks that fraudulently claim another person’s identity. Additionally, given the broad range of individual needs, constraints, capacities, and preferences, online services must be designed with flexibility and customer experience in mind to support broad and enduring participation and access to online services.

Digital identity risks are dynamic and exist along a continuum. Consequently, a digital identity risk management approach should seek to manage risks using outcome-based approaches that are designed to meet the organization’s unique needs. These guidelines define specific assurance levels that operate as baseline control sets. These assurance levels provide multiple benefits, including a starting point for organizations in their risk management journey and a common structure for supporting interoperability between different entities. It is, however, impractical to create assurance levels that can comprehensively address the entire spectrum of risks, threats, or considerations that an organization will face when deploying an identity solution. For this reason, these guidelines promote a risk-based approach to digital identity solution implementation rather than a compliance-oriented approach, and organizations are encouraged to tailor their control implementations based on the processes defined in these guidelines.

Additionally, risks associated with digital identity stretch beyond the potential impacts to the organization providing online services. These guidelines endeavor to robustly and explicitly account for risks to individuals, communities, and other organizations. Organizations should also consider how digital identity decisions might affect, or need to accommodate, the individuals who interact with the organization’s programs and services. Privacy and customer experience for individuals should be considered along with security. Additionally, organizations should consider their digital identity approach alongside other mechanisms for identity management, such as those used in call centers and in-person interactions. By taking a customer-centric and continuously informed approach to mission delivery, organizations have an opportunity to incrementally build trust with the populations they serve, improve customer experience, identify issues more quickly, and provide individuals with appropriate and effective redress options.

The composition, models, and availability of identity services have significantly changed since the first version of SP 800-63 was released, as have the considerations and challenges of deploying secure, private, and usable services to users. This revision addresses these challenges by presenting guidance and requirements based on the roles and functions that entities perform as part of the overall digital identity model.

Additionally, this publication provides instruction for credential service providers (CSPs), verifiers, and relying parties (RPs), to supplement the NIST Risk Management Framework [NISTRMF] and its component publications. It describes the risk management processes that organizations should follow to implement digital identity services and expands upon the NIST RMF by outlining how customer experience considerations should be incorporated. It also highlights the importance of considering impacts on enterprise operations and assets, individuals, and other organizations. Furthermore, digital identity management processes for identity proofing, authentication, and federation typically involve processing personal information, which can present privacy risks. Therefore, these guidelines include privacy requirements and considerations to help mitigate potential associated risks.

Finally, while these guidelines provide organizations with technical requirements and recommendations for establishing, maintaining, and authenticating the digital identity of subjects who access digital systems over a network, they also recommend integration with systems and processes that are often outside of the control of identity and IT teams. As such, these guidelines provide considerations to improve coordination with organizations and deliver more effective, modern, and customer-driven online services.

Scope and Applicability

These guidelines applies to all online services for which some level of assurance in a digital identity is required, regardless of the constituency (e.g., the public, business partners, and government employees and contractors). For this publication, “person” refers only to natural persons.

These guidelines primarily focus on organizational services that interact with external users, such as individuals accessing public benefits or private-sector partners accessing collaboration spaces. However, they also apply to federal systems accessed by employees and contractors. The Personal Identity Verification (PIV) of Federal Employees and Contractors standard [FIPS201], and its corresponding set of Special Publications and organization-specific instructions, extend these guidelines for the federal enterprise by providing additional technical controls and processes for issuing and managing Personal Identity Verification (PIV) Cards, binding additional authenticators as derived PIV credentials, and using federation architectures and protocols with PIV systems.

Online services not covered by these guidelines include those associated with national security systems as defined in [44 U.S.C. § 3552(b)(6)]. Private-sector organizations and state, local, and tribal governments whose digital processes require varying levels of digital identity assurance may consider the use of these standards where appropriate.

These guidelines address logical access to online systems, services, and applications. They do not specifically address physical access control processes. However, the processes specified in these guidelines can be applied to physical access use cases where appropriate. Additionally, these guidelines do not explicitly address some subjects including, but not limited to, machine-to-machine authentication, interconnected devices (e.g., Internet of Things [IoT] devices), or access to Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) on behalf of subjects.

How to Use This Suite of SPs

These guidelines support the mitigation of the negative impacts of errors that occur during the functions of identity proofing, authentication, and federation. Section 3, Digital Identity Risk Management, describes the risk assessment process and how the results of the risk assessment and additional context inform the selection of controls to secure the identity proofing, authentication, and federation processes. Controls are selected by determining the assurance level required to mitigate each applicable type of digital identity error for a particular service based on risk and mission.

Specifically, organizations are required to select an assurance level1 for each of the following functions:

- Identity Assurance Level (IAL) refers to identity proofing functions.

- Authentication Assurance Level (AAL) refers to authentication functions.

- Federation Assurance Level (FAL) refers to federation functions when the relying party (RP) is connected to a credential service provider (CSP) or an identity provider (IdP) through a federated protocol.

SP 800-63 is organized as the following suite of volumes:

- SP 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines describes the digital identity models, risk assessment methodology, and processes for selecting assurance levels for identity proofing, authentication, and federation. SP 800-63 contains both normative and informative material.

- [SP800-63A]: provides requirements for identity proofing and the remote or in-person enrollment of applicants, who wish to gain access to resources at each of the three IALs. It details the responsibilities of CSPs with respect to establishing and maintaining subscriber accounts and binding CSP-issued or subscriber-provided authenticators to the subscriber account. SP 800-63A contains both normative and informative material.

- [SP800-63B] provides requirements for authentication processes that can be used at each of the three AALs, including choices of authenticators. It also provides recommendations on events that can occur during the lifetime of authenticators (e.g., invalidation in the event of loss or theft). SP 800-63B contains both normative and informative material.

- [SP800-63C] provides requirements on the use of federated identity architectures and assertions to convey the results of authentication processes and relevant identity information to an organization’s application. SP 800-63C contains both normative and informative material.

Enterprise Risk Management Requirements and Considerations

Effective enterprise risk management is multidisciplinary by design and involves the consideration of varied sets of factors and expectations. In a digital identity risk management context, these factors include, but are not limited to, information security, fraud, privacy, and customer experience. It is important for risk management efforts to weigh these factors as they relate to enterprise assets and operations, individuals, and other organizations.

During the process of analyzing factors that are relevant to digital identity, organizations might determine that measures outside of those specified in this publication are appropriate in certain contexts (e.g., where privacy or other legal requirements exist or where the output of a risk assessment leads the organization to determine that additional measures or alternative procedural safeguards are appropriate). Organizations, including federal agencies, can employ compensating or supplemental controls that are not specified in this publication. They can also consider partitioning the functionality of an online service to allow less sensitive functions to be available at a lower level of assurance to improve access without compromising security.

The considerations detailed below support enterprise risk management efforts and encourage informed and customer-centered service delivery. While this list of considerations is not exhaustive, it highlights a set of cross-cutting factors that are likely to impact decision-making associated with digital identity management.

Security, Fraud, and Threat Prevention

It is increasingly important for organizations to assess and manage digital identity security risks, such as unauthorized access due to impersonation. As organizations consult these guidelines, they should consider potential impacts to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information and information systems that they manage, and that their service providers and business partners manage, on behalf of the individuals and communities that they serve.

Federal agencies implementing these guidelines are required to meet statutory responsibilities, including those under the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014 [FISMA] and related NIST standards and guidelines. NIST recommends that non-federal organizations implementing these guidelines follow comparable standards (e.g., ISO/IEC 27001) to ensure the secure operation of their digital systems.

FISMA requires federal agencies to implement appropriate controls to protect federal information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, or modification. The NIST RMF [NISTRMF] provides a process that integrates security, privacy, and cyber supply chain risk management activities into the system development life cycle. It is expected that federal agencies and organizations that provide services under these guidelines have already implemented the controls and processes required under FISMA and associated NIST risk management processes and publications.

The controls and requirements encompassed by the identity, authentication, and federation assurance levels under these guidelines augment but do not replace or alter the information and information system controls determined under FISMA and the RMF.

As threats evolve, it is important for organizations to assess and manage identity-related fraud risks associated with identity proofing and authentication processes. As organizations consult these guidelines, they should consider the evolving threat environment, the availability of innovative anti-fraud measures in the digital identity market, and the potential impacts of identity-related fraud on their systems and users. This is particularly important for public-facing online services where the impact of identity-related fraud on digital government service delivery, public trust, and organization reputation can be substantial.

This version enhances measures to combat identity theft and identity-related fraud by repurposing IAL1 as a new assurance level, updating authentication risk and threat models to account for new attacks, providing new options for phishing-resistant authentication, introducing requirements to prevent automated attacks against enrollment processes, and preparing for new technologies (e.g., mobile driver’s licenses and verifiable credentials) that can leverage strong identity proofing and authentication.

Privacy

When designing, implementing, and managing digital identity systems, it is imperative to consider the potential of that system to create privacy-related problems for individuals when processing (e.g., collection, storage, use, and destruction) personal information and the potential impacts of problematic data actions. If a breach of personal information or a release of sensitive information occurs, organizations need to ensure that the privacy notices describe, in plain language, what information was improperly released and, if known, how the information was exploited.

Organizations need to demonstrate how organizational privacy policies and system privacy requirements have been implemented in their systems. These guidelines recommend that organizations take steps to implement digital identity risk management with privacy in mind, which can be supported by referencing:

- [NISTPF] NIST Privacy Framework, which enables privacy engineering practices that support privacy by design concepts and helps organizations protect individuals’ privacy

- [PrivacyAct] of 1974, which established fair information practices for the collection, maintenance, use, and disclosure of information about individuals that is maintained by federal agencies in systems of records

- [M-03-22] OMB Guidance for Implementing the Privacy Provisions of the E-Government Act of 2002, which requires the performance and public notification of privacy impact assessments (PIAs) that are required for processing or storing personal information

- [SP800-53] Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations, which lists privacy controls that can be implemented to mitigate the risks identified in the privacy risk and impact assessments

- [SP800-122] Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), which assists federal agencies in understanding what personal information is; the relationship between protecting the confidentiality of personal information; privacy and the Fair Information Practices; and safeguards for protecting personal information

Furthermore, each volume of SP 800-63 contains a specific section that provides detailed privacy guidance and considerations for implementing the processes, controls, and requirements presented in that volume as well as normative requirements on data collection, retention, and minimization.

Customer Experience

It is essential that these guidelines provide organizations with the ability to create modern, streamlined, and responsive customer experiences. To do this, the guidelines allow organizations to factor in the capabilities and expectations of users when making decisions and trade-offs in the risk management process. Organizations that implement these guidelines must understand their user populations, capabilities, and limitations as part of setting an effective digital identity risk management strategy.

There have been several major additions to these guidelines to ensure responsive and effective customer experiences. In addition to adding new technologies to each of the volumes, as applicable, this volume introduces two key concepts:

- Control tailoring. Control tailoring allows organizations to make informed risk-based decisions to deploy technologies and processes that work for their users and adjust their baseline controls through informed decision-making to meet customer experience needs.

- Continuous improvement programs. Establishing a continuous evaluation program provides organizations with the ability to evaluate how well they are mitigating risks and meeting the needs of their users. Through metrics and cross-functional assessment programs, this guideline sets a foundation for a data-driven approach to providing effective, modern solutions that support organizations’ extensive user populations.

These two concepts are discussed in detail in Sec. 3 of this document.

As a part of improving customer experience, these guidelines also emphasize the need to provide options for users to “meet the customer where they are.” When coupled with a continuous improvement strategy and customer-centered design, this can help identify the opportunities, processes, business partners, and multi-channel identity proofing and service delivery methods that best support the needs of the populations that an organization serves.

Additionally, usability refers to the extent to which a system, product, or service can be used to achieve goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use. Usability supports the major objectives of customer experience, service delivery, and security, and requires an understanding of the people who interact with a digital identity system or process, as well as their unique capabilities and context of use.

Readers of this guideline should take a holistic approach to considering the interactions that each user will engage in throughout the process of enrolling in and authenticating to a service. Throughout the design and development of a digital identity system or process, it is important to conduct usability evaluations with representative users and perform realistic scenarios and tasks in appropriate contexts of use. Additionally, following usability guidelines and considerations can help organizations meet their customer experience goals. Digital identity management processes should be designed and implemented so that it is easy for users to do the right thing, hard to do the wrong thing, and easy to recover when the wrong thing happens.

\clearpage

Notations

This guideline uses the following typographical conventions in text:

- Specific terms in CAPITALS represent normative requirements. When these same terms are not in CAPITALS, the term does not represent a normative requirement.

- The terms “SHALL” and “SHALL NOT” indicate requirements to be followed strictly in order to conform to the publication and from which no deviation is permitted.

- The terms “SHOULD” and “SHOULD NOT” indicate that among several possibilities, one is recommended as particularly suitable without mentioning or excluding others, that a certain course of action is preferred but not necessarily required, or that (in the negative form) a certain possibility or course of action is discouraged but not prohibited.

- The terms “MAY” and “NEED NOT” indicate a course of action permissible within the limits of the publication.

- The terms “CAN” and “CANNOT” indicate a possibility and capability — whether material, physical, or causal — or, in the negative, the absence of that possibility or capability.

Document Structure

This document is organized as follows. Each section is labeled as either normative (i.e., mandatory for compliance) or informative (i.e., not mandatory).

- Section 1 introduces the document. This section is informative.

- Section 2 describes a general model for digital identity. This section is informative.

- Section 3 describes the digital identity risk model. This section is normative.

- The References section contains a list of publications that are cited in this document. This section is informative.

- Appendix A contains a selected list of abbreviations used in this document. This appendix is informative.

- Appendix B contains a glossary of selected terms used in this document. This appendix is informative.

- Appendix C contains a summarized list of changes in this document’s history. This appendix is informative.

-

When described generically or bundled, these guidelines will refer to IAL, AAL, and FAL as xAL. Each xAL has three assurance levels. ↩

Digital Identity Model

This section is informative.

Overview

These guidelines use digital identity models that reflect technologies and architectures that are currently available in the market. These models have a variety of entities and functions and vary in complexity. Simple models group functions (e.g., creating subscriber accounts, providing attributes) under a single entity. More complex models separate these functions among multiple entities.

The roles and functions found in these digital identity models include:

Subject: In these guidelines, a subject is a person and is represented by one of three roles, depending on where they are in the digital identity process.

- Applicant — A subject to be identity-proofed and enrolled.

- Subscriber — A subject who has successfully completed the identity proofing and enrollment process or who has been successfully authenticated to an online service.

- Claimant — A subject “making a claim” to be eligible for authentication.

Service provider: Service providers can perform any combination of functions involved in granting access to and delivering online services, such as a credential service provider, relying party, verifier, and identity provider.

Credential service provider (CSP): CSP functions include identity proofing applicants, enrolling them into their identity service, establishing subscriber accounts, and binding authenticators to those accounts. A subscriber account is the CSP’s established record of the subscriber, the subscriber’s attributes, and associated authenticators. CSP functions may be performed by an independent third party.

Relying party (RP): RPs provide online transactions and services and rely upon a verifier’s assertion of a subscriber’s identity to grant access to those services. When using federation, the RP accesses the information in the subscriber account through assertions from an identity provider (IdP).

Verifier: A verifier confirms the claimant’s identity by verifying the claimant’s possession and control of one or more authenticators using an authentication protocol. To do this, the verifier needs to confirm the binding of the authenticators with the subscriber account and check that the subscriber account is active.

Identity provider (IdP): When using federation, the IdP manages the subscriber’s primary authenticators and issues assertions derived from the subscriber account.

While presented as separate roles, the functions of the CSP, verifier, and IdP may be performed by a single entity or distributed across multiple entities, depending on the implementation (see Sec. 2.5).

Identity Proofing and Enrollment

[SP800-63A], Digital Identity Guidelines: Identity Proofing and Enrollment, provides general guidance information and normative requirements for the identity proofing and enrollment processes as well as IAL-specific requirements.

[SP800-63A] provides general information and normative requirements for the identity proofing and enrollment processes as well as requirements that are specific to IALs.

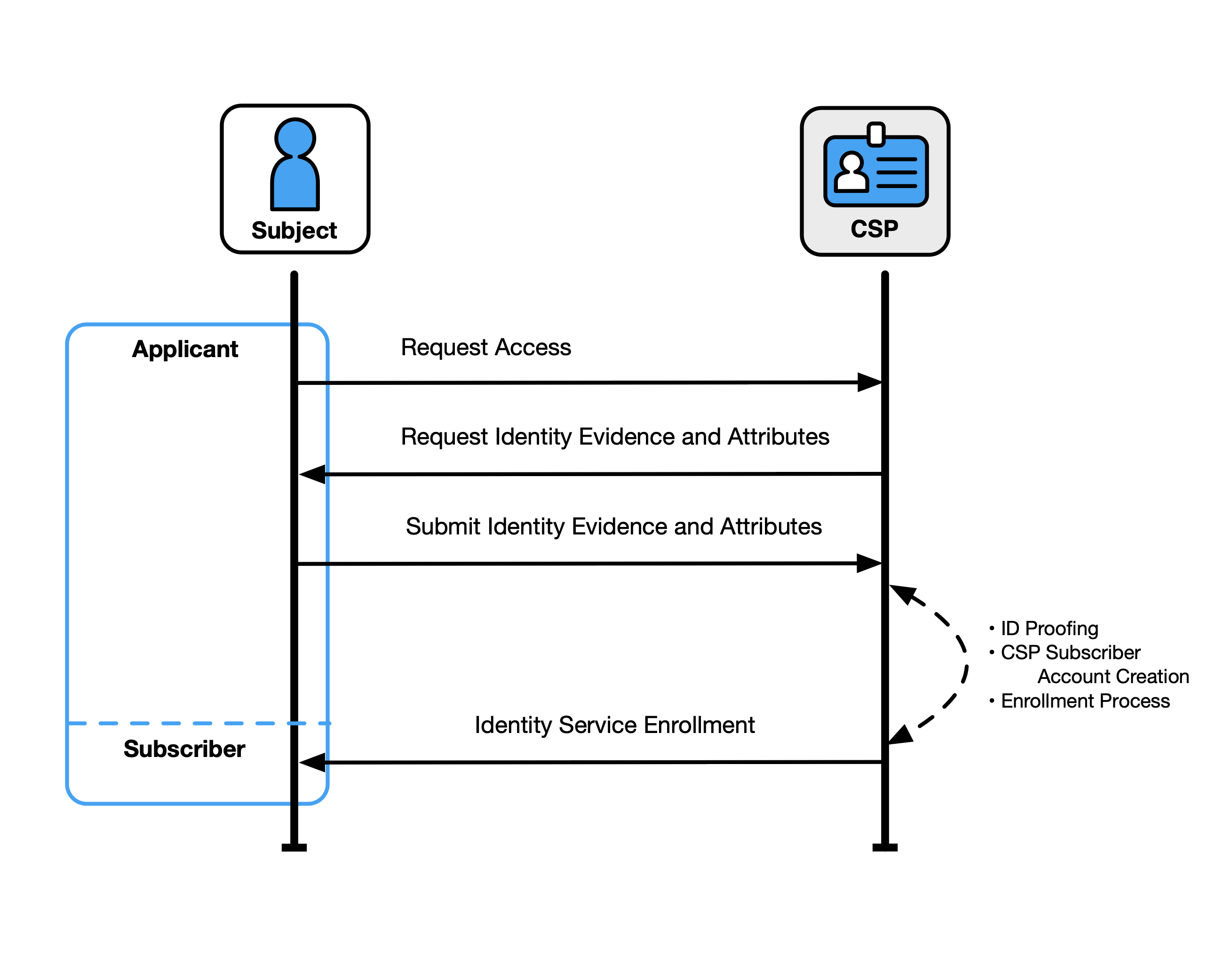

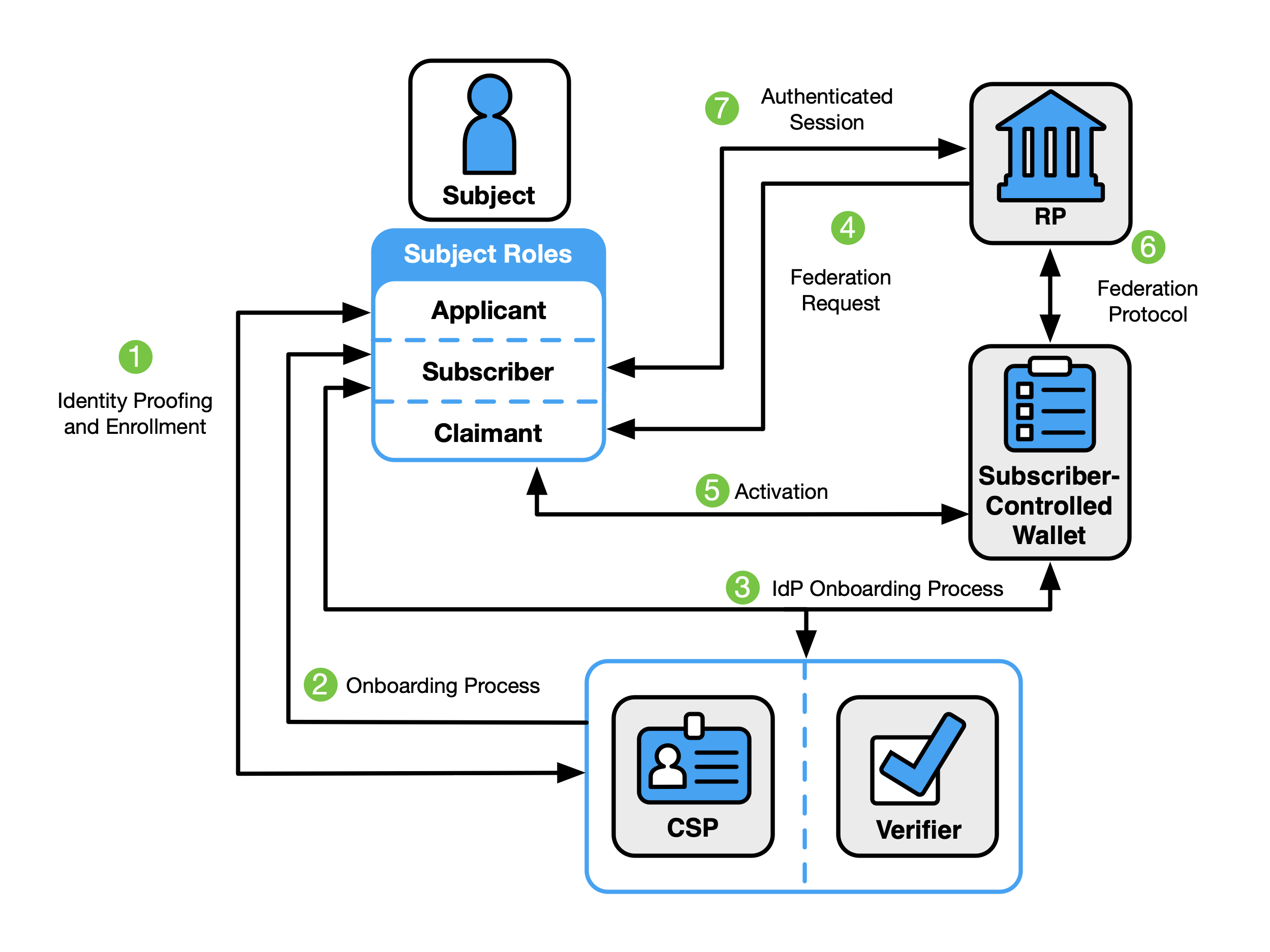

Figure 1 illustrates a common transaction sequence for the identity proofing and enrollment functions.

Identity proofing and enrollment begin when an applicant initiates identity proofing, often by attempting to access an online application served by the CSP. The CSP or its component service requests identity evidence and attributes from the applicant, which the applicant submits via an online or in-person transaction. The CSP resolves the user (i.e., uniquely distinguishes the user), validates the accuracy and authenticity of the evidence, and validates the accuracy of the attributes. If the applicant is successfully identity-proofed, they are enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber of that CSP. A unique subscriber account is then created, and one or more authenticators are registered to that account.

Subscribers have a responsibility to maintain control of their authenticators (e.g., guard against theft) and comply with CSP policies to remain in good standing with the CSP.

Fig. 1. Sample identity proofing and enrollment digital identity model

Subscriber Accounts

At the time of enrollment, the CSP establishes a subscriber account to uniquely identify each subscriber and record information about the subscriber and any authenticators bound to that subscriber account.

See Sec. 5 of [SP800-63A], subscriber accounts, for more information and normative requirements.

Authentication and Authenticator Management

[SP800-63B], Authentication and Authenticator Management, provides normative descriptions of permitted authenticator types, their characteristics (e.g., phishing resistance), and authentication processes appropriate for each AAL.

Authenticators

An authenticator is a means of demonstrating the control or possession of one or more factors in an authentication protocol. These guidelines define three types of authentication factors used for authentication:

- Something you know (e.g., a password)

- Something you have (e.g., a device containing a cryptographic key)

- Something you are (e.g., a fingerprint or other biometric characteristic data)

Single-factor authentication requires only one of the above factors, most often “something you know.” Multiple instances of the same factor still constitute single-factor authentication. For example, a user-generated PIN and a password do not constitute two factors as they are both “something you know.” Multi-factor authentication (MFA) refers to the use of more than one distinct factor.

This guideline specifies that authenticators always contain or comprise a secret. The secrets contained in an authenticator are based on either key pairs (i.e., asymmetric cryptographic keys) or shared secrets, including symmetric cryptographic keys, seeds for generating one-time passwords (OTP), and passwords. Asymmetric key pairs are comprised of a public key and a related private key. The private key is stored on the authenticator and is only available for use by the claimant who possesses and controls the authenticators. Symmetric keys generally are chosen at random, complex and long enough to thwart network-based guessing attacks, and stored in hardware or software that the subscriber controls.

Passwords used locally as an activation factor for a multi-factor authenticator are referred to as activation secrets. An activation secret is used to obtain access to a stored authentication key and remains within the authenticator and its associated user endpoint. An example of an activation secret would be the PIN used to activate a PIV card.

Biometric characteristics are unique, personal attributes that can be used to verify the identity of a person who is physically present at the point of authentication. This includes, facial features, fingerprints, and iris patterns, among others. While biometric characteristics cannot be used for single-factor authentication, they can be used as an authentication factor for multi-factor authentication in combination with a physical authenticator (i.e., something you have).

Some commonly used authentication methods do not contain or comprise secrets and are, therefore, not acceptable for use under these guidelines, such as:

- Knowledge-based authentication (KBA), where the claimant is prompted to answer questions that are presumably known only by the claimant, does not constitute an acceptable secret for digital authentication.

- A biometric characteristic does not constitute a secret and cannot be used as a single-factor authenticator.

Authentication Process

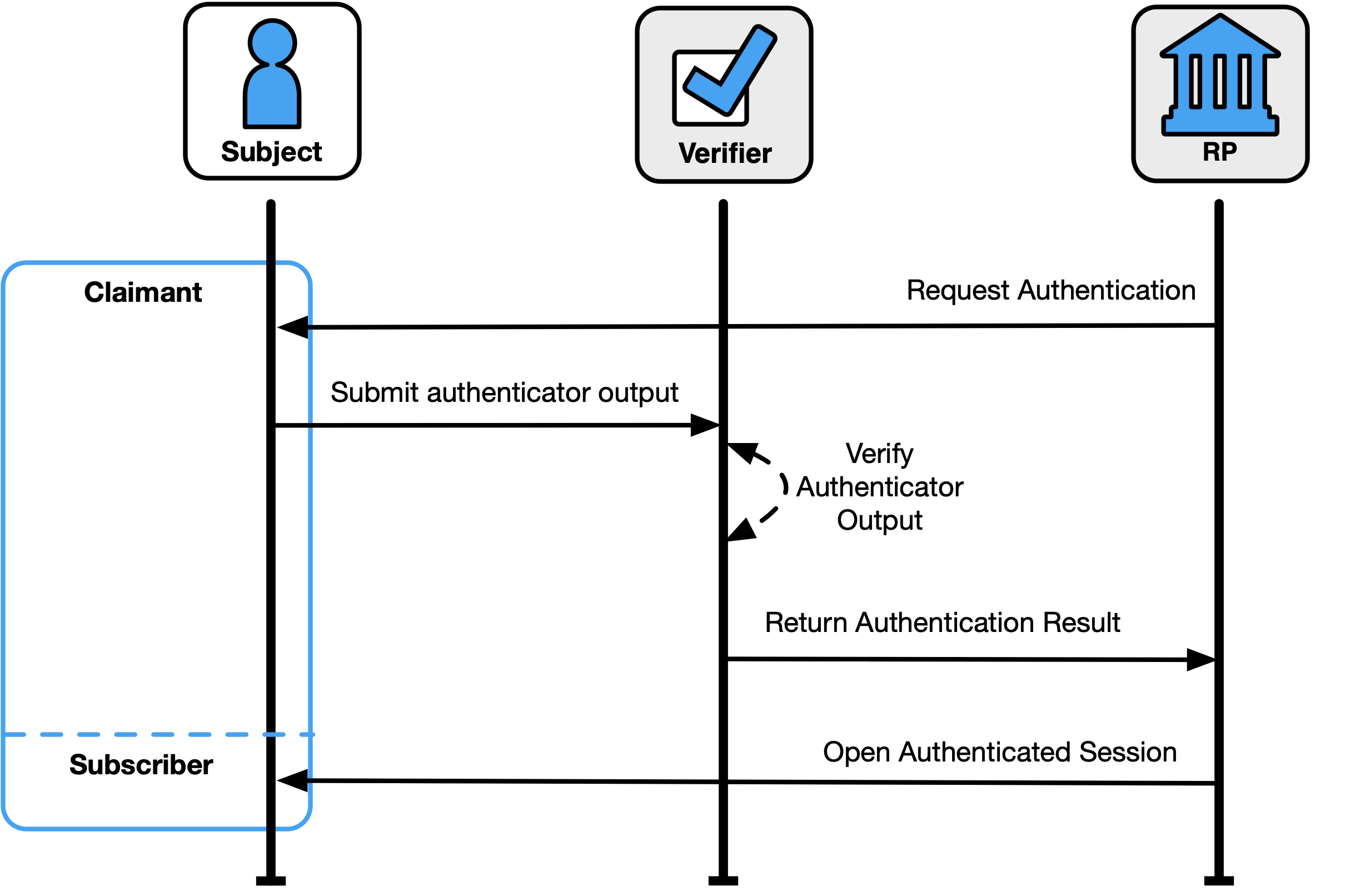

The authentication process enables an RP to trust that a claimant is who they say they are to some level of assurance. The sample authentication process in Fig. 2 shows interactions between the RP, a claimant, and a verifier/CSP. The verifier is a functional role and is frequently implemented in combination with the CSP, RP, or both (as shown in Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Sample authentication process

A successful authentication process demonstrates that the claimant has possession and control of one or more valid authenticators that are bound to the subscriber’s identity. In general, this is done using an authentication protocol that involves an interaction between the verifier and the claimant, where the claimant uses one or more authenticators to generate the authenticator output to be sent to the verifier. The verifier verifies the output and passes a positive result to the RP. The RP then opens an authenticated session with the verified subscriber.

The exact nature of the interaction is important in determining the overall security of the system. Well-designed protocols protect the integrity and confidentiality of communication between the claimant and the verifier both during and after the authentication and can help limit the damage done by an attacker masquerading as a legitimate verifier (i.e., phishing).

Federation and Assertions

Normative requirements can be found in [SP800-63C], Federation and Assertions.

Section III of OMB [M-19-17], Enabling Mission Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management, directs agencies to support cross-government identity federation and interoperability. The term federation can be applied to several different approaches that involve the sharing of information between different trust domains, and may differ based on the kind of information that is being shared between the domains. These guidelines address the federation processes that allow for the conveyance of identity and authentication information based on trust agreements across a set of networked systems through federation assertions.

There are many benefits to using federated architectures including, but not limited to:

- Enhancing user experience (e.g., a subject can be identity-proofed once but their subscriber account used at multiple RPs)

- Reducing costs for both the subscriber (e.g., reduction in authenticators) and the organization (e.g., reduction in information technology infrastructure and a streamlined architecture)

- Minimizing data exposed to RPs by using pseudonymous identifiers and derived attribute values instead of copying account values to each application

- Supporting mission success, since organizations will need to focus fewer resources on complex identity management processes

While the federation process is generally the preferred approach to authentication when the RP and IdP are not administered together under a common security domain, federation can also be applied within a single security domain for a variety of benefits, including centralized account management and technical integration.

These guidelines are agnostic to the identity proofing, authentication, and federation architectures that an organization selects, and they allow organizations to deploy a digital identity scheme according to their own requirements. However, there are scenarios in which federation could be more efficient and effective than establishing identity services that are local to the organization or individual applications, such as:

- Potential users already have an authenticator at or above the required AAL.

- Multiple types of authenticators are required to cover all possible user communities.

- An organization does not have the necessary infrastructure to support the management of subscriber accounts (e.g., account recovery, authenticator issuance, help desk).

- There is a desire to allow primary authenticators to be added and upgraded over time without changing the RP’s implementation.

- There are different environments to be supported, since federation protocols are network-based and allow for implementation on a wide variety of platforms and languages.

- Potential users come from multiple communities, each with its own existing identity infrastructure.

- The organization needs the ability to centrally manage account life cycles, including account revocation and the binding of new authenticators.

\clearpage

An organization might want to consider accepting federated identity attributes if any of the following apply:

- Pseudonymity is required, necessary, feasible, or important to stakeholders accessing the service.

- Access to the service requires a defined list of attributes.

- Access to the service requires at least one derived attribute value.

- The organization is not the authoritative or issuing source for required attributes.

- Attributes are required temporarily during use (e.g., to make an access decision), and the organization does not need to retain the data.

Examples of Digital Identity Models

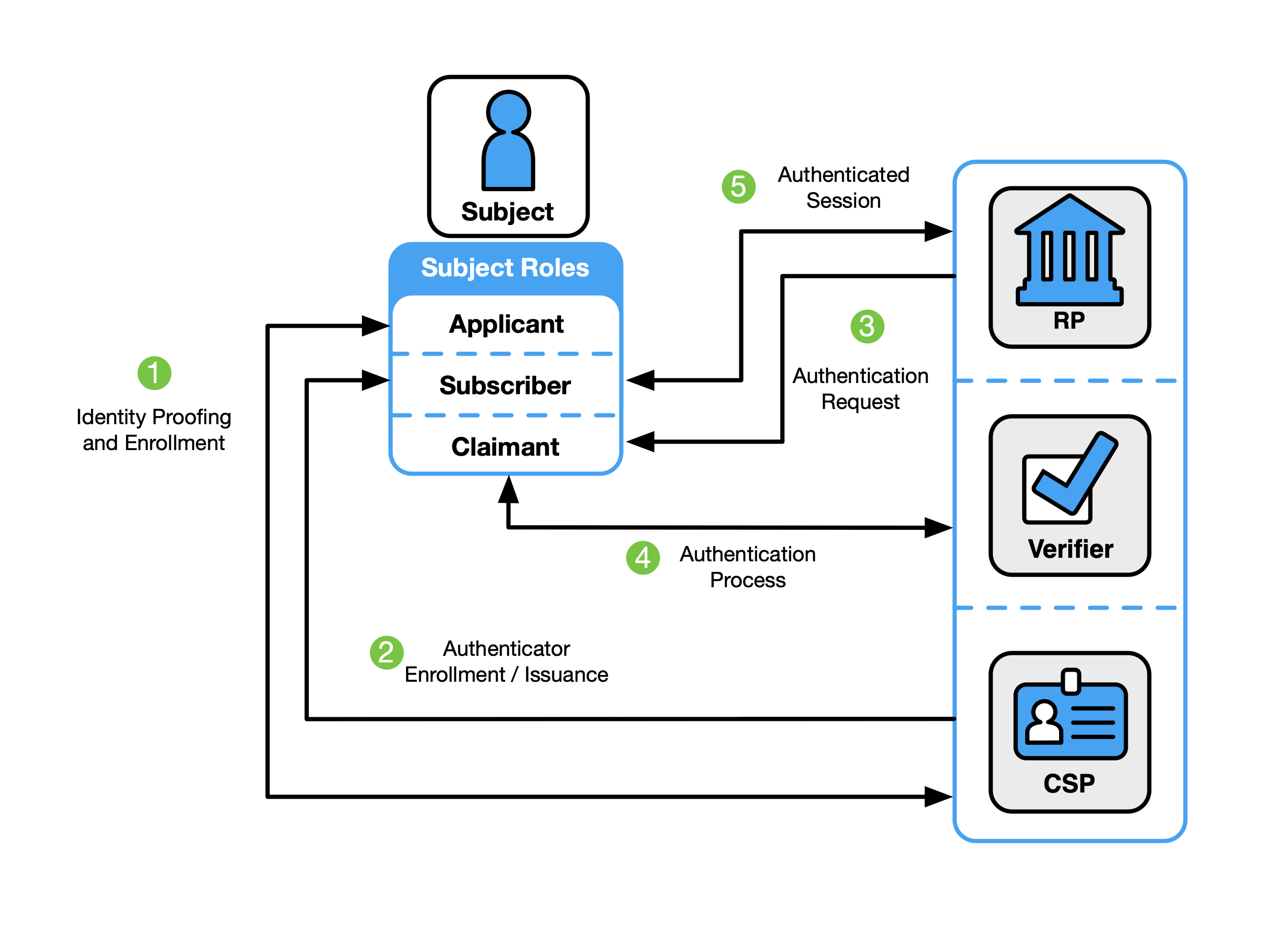

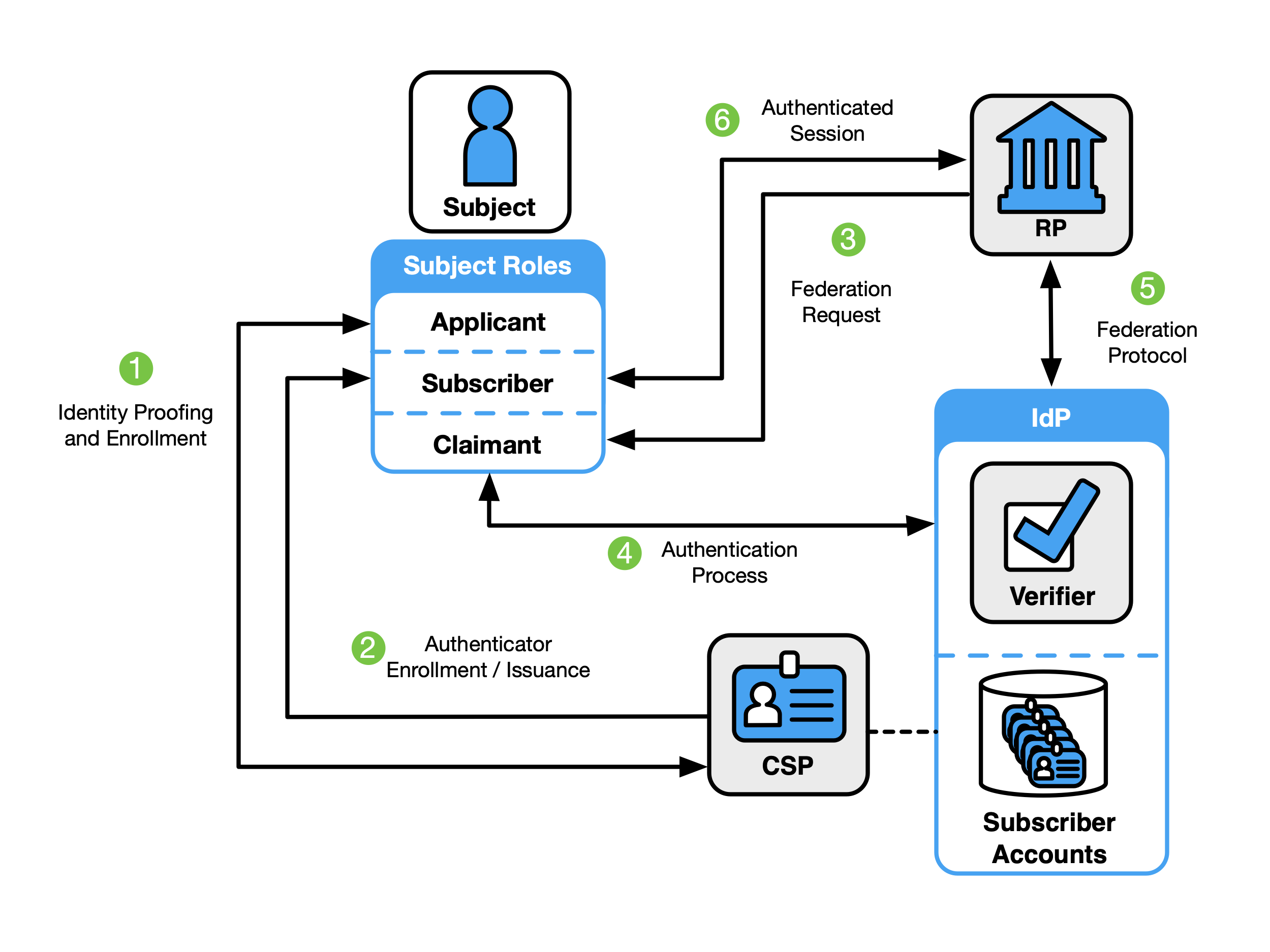

The entities and interactions that comprise the non-federated digital identity model are illustrated in Fig. 3. The general-purpose federated digital identity model is illustrated in Fig. 4, and a federated digital identity model with a subscriber-controlled wallet is illustrated in Fig. 5.

In the two cases described in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, the verifier does not always need to communicate in real time with the CSP to complete the authentication activity (e.g., digital certificates can be used). Therefore, the line between the verifier and the CSP represents a logical link between the two entities. In some implementations, the verifier, RP, and CSP functions are distributed. However, if these functions reside on the same platform, the interactions between the functions are signals between applications or application modules that run on the same system rather than using network protocols.

Non-Federated Digital Identity Model

Fig. 3. Non-federated digital identity model example

Figure 3 shows an example of a common sequence of interactions in the non-federated model. Other sequences could also achieve the same functional requirements. One common sequence of interactions for identity proofing and enrollment activities is represented as follows:

- Step 1: An applicant applies to a CSP through an identity proofing and enrollment process. The CSP identity-proofs that applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful identity proofing, the applicant is enrolled into the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the CSP and the subscriber. The CSP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data. The subscriber maintains their authenticators.

Steps 3 through 5 can immediately follow steps 1 and 2 or be done at a later time. The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators to perform digital authentication in the non-federated model is as follows:

- Step 3: The claimant initiates an online interaction with the RP and the RP requests that the claimant authenticate.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier function through an authentication process:

- The verifier interacts with the CSP to verify the binding of the claimant’s identity to their authenticators in the subscriber account and to optionally obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- The CSP or verifier functions of the service provider give information about the subscriber. The RP requests the attributes that it requires from the CSP. The RP optionally uses this information to make authorization decisions.

- Step 5: An authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

Federated Digital Identity Model With General-Purpose IdP

Fig. 4. Federated digital identity model example

Figure 4 shows an example of those same common interactions in a federated model.

- Step 1: An applicant applies to a CSP through an identity proofing and enrollment process. The CSP identity-proofs that applicant.

- Step 2: Upon successful identity proofing, the applicant is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- A subscriber account and corresponding authenticators are established between the CSP and the subscriber.

- The IdP is provisioned either directly by the CSP or indirectly through access to attributes of the subscriber account. The CSP maintains the subscriber account, its status, and the enrollment data collected in accordance with the records retention and disposal requirements described in Sec. 3.1 of [SP800-63A]. The subscriber maintains their authenticators. The IdP maintains its view of the subscriber account, any federated identifiers assigned to the subscriber account, and any policies and decisions regarding the release of attributes and information to RPs.

The usual sequence of interactions involved in using one or more authenticators in the federated model to perform digital authentication is as follows:

- Step 3: The RP requests that the claimant authenticate and requests any attributes needed from the IdP to make access or authorization decisions. This triggers a request for federated authentication to the IdP.

- Step 4: The claimant proves possession and control of the authenticators to the verifier function of the IdP through an authentication process.

- The binding of the claimant’s authenticators are verified with those bound to the claimed subscriber account and optionally to obtain additional subscriber attributes.

- Step 5: The RP and the IdP communicate through a federation protocol. The IdP provides an assertion and any necessary additional attributes to the RP through a federation protocol. The RP verifies the assertion to establish confidence in the identity and attributes of a subscriber for access to an online service at the RP. RPs use a subscriber’s federated identity (pseudonymous or non-pseudonymous), IAL, AAL, FAL, and other factors to make authorization decisions.

- Step 6: An authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

Federated Digital Identity Model with Subscriber-Controlled Wallet

Fig. 5. Federated Digital Identity Model With Subscriber-Controlled Wallet Example

Figure 5 shows an example of the interactions in a federated digital identity model in which the subscriber controls a device with software (i.e., a digital wallet) or an account with a cloud service provider (i.e., a hosted-wallet) that acts as the IdP. In the terminology of the “three-party model,” the CSP is the issuer, the IdP is the holder (i.e., the users device or agent operating on their behalf), and the RP is the verifier. In this model, it is common for the RP to establish a trust agreement with the CSP using a federation authority, as defined in Sec. 3.5 of [SP800-63C]. This arrangement allows the RP to accept assertions from the subscriber-controlled wallet without needing a direct trust relationship with the wallet, as described in Sec. 5 of [SP800-63C].

- Step 1: An applicant applies to a CSP identity proofing and enrollment process.

- Step 2: Upon successful identity proofing, the applicant goes through an onboarding process and is enrolled in the identity service as a subscriber.

- Step 3: The subscriber-controlled wallet is onboarded by the CSP, allowing the wallet to act in the role of IdP in later steps.

- The subscriber authenticates to the CSP’s issuance functionality by authenticating to the subscriber account or completes an abbreviated proofing process to demonstrate that they are the same user represented by the subscriber account.

- The subscriber activates the subscriber-controlled wallet using an activation factor.

- The wallet generates or chooses a signing key and corresponding verification key, including proof of a key held by the wallet.

- The CSP creates one or more attribute bundles that include subscriber attributes and the wallet’s verification key (or a reference to that key).

- The CSP issues the attribute bundle with corresponding verification key into the subscriber-controlled wallet.

Other protocols and specifications often refer to attribute bundles as credentials. These guidelines use the term credentials to refer to a different concept. To avoid a conflict, the term attribute bundle is used within these guidelines. Normative requirements for attribute bundles can be found in Sec. 3.12.1 of [SP800-63C].

\clearpage

The usual sequence of interactions involved in providing an assertion to the RP from a subscriber-controlled wallet is as follows:

- Step 4: The RP requests that the claimant authenticate. This triggers a request for federated authentication to the wallet.

- Step 5: The claimant proves possession and control of the subscriber-controlled wallet.

- The claimant activates the wallet using an activation factor or authenticates to a hosted service if the subscriber-controlled wallet is hosted by a service provider.

- The wallet prepares an assertion that includes the attribute bundle provided by the CSP for the subscriber account.

- Step 6: The RP and the wallet communicate through a federation protocol. The wallet provides an assertion, the CSP-signed attribute bundles and optional additional attributes to the RP through a federation protocol. The RP verifies the assertion to establish confidence in the identity and attributes of a subscriber for access to an online service at the RP. RPs use a subscriber’s federated identity (pseudonymous or non-pseudonymous), IAL, AAL, FAL, and other factors to make authorization decisions.

- Step 7: An authenticated session is established between the subscriber and the RP.

Digital Identity Risk Management

This section is normative.

This section describes the methodology for assessing digital identity risks associated with online services, including residual risks to users of the online service, the service provider organization, and its mission and business partners. It offers guidance on selecting usable, privacy-enhancing security, and anti-fraud controls that mitigate those risks. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of continuously evaluating the performance of the selected controls.

The Digital Identity Risk Management (DIRM) process focuses on the identification and management of risks according to two dimensions: (1) risks that result from operating the online service that might be addressed by an identity system and (2) additional risks that are introduced as a result of implementing the identity system.

The first dimension of risk informs initial assurance level selections and seeks to identify risks associated with a compromise of the online service that might be addressed by an identity system. For example:

- Identity proofing: Negative impacts that could reasonably be expected if an imposter were to gain access to a service or receive a credential using the identity of a legitimate user (e.g., an attacker successfully impersonates someone)

- Authentication: Negative impacts that could reasonably be expected if a false claimant accessed an account that was not rightfully theirs (e.g., an attacker who compromises or steals an authenticator), often referred to as an account takeover attack

- Federation: Negative impacts that could reasonably be expected if the wrong subject successfully accessed an online service, system, or data (e.g., compromising or replaying an assertion)

If there are risks associated with a compromise of the online service that could be addressed by an identity system, an initial assurance level is selected and the second dimension of risk is then considered.

The second dimension of risk seeks to identify the risks posed by the identity system itself and informs the tailoring process. Tailoring provides a process to modify an initially assessed assurance level, implement compensating or supplemental controls, or modify selected controls based on ongoing detailed risk assessments in areas such as privacy, usability, and resilience to real-world threats.

Examples of the types of impact that can result from risks introduced by the identity system itself include:

- Identity proofing: Impacts of not successfully identity proofing and enrolling a legitimate subject due to barriers faced by the subject throughout the process of identity proofing, falling victim to a breach of information that was collected and retained to support identity proofing processes, or the initial IAL failing to completely address specific threats, threat actors, and fraud

- Authentication: Impacts of failing to authenticate the correct subject due to barriers faced by the subject in presenting their authenticator, including barriers due to usability issues; the initial AAL failing to completely address targeted account takeover models or specific authenticator types fail to mitigate anticipated attacks

- Federation: Impacts of releasing real subscriber attributes to the wrong online service or system or releasing incorrect or fake attributes to a legitimate RP

The outcomes of the DIRM process depend on the role that an entity plays within the digital identity model.

- For relying parties, the intent of this process is to determine the assurance levels and any tailoring required to protect online services and the applications, transactions, and systems that comprise or are impacted by those services. This directly contributes to the selection, development, and procurement of CSP services. Federal RPs SHALL implement the DIRM process for all online services.

- For credential service providers and identity providers, the intent of this process is to design service offerings that meet the requirements of the defined assurance levels, continuously guard against compromises to the identity system, and meet the needs of RPs. Whenever a service offering deviates from normative guidance, those deviations SHALL be clearly communicated to the RPs that utilize the service.

CSPs and IdPs are expected to offer services at assurance levels that are requested by the RPs they serve. However, CSPs and IdPs that choose to deviate from this guideline or augment their services are expected to conduct an abbreviated digital identity risk assessment and document their modifications in a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement that is provided to RPs (see Sec. 3.4.4).

This process augments the risk management processes required by [FISMA]. The results of the DIRM impact assessment for the online service may be different from the FISMA impact level for the underlying application or system. Identity process failures can result in different levels of impact for various user groups. For example, the overall assessed FISMA impact level for a payment system may result in a ‘FISMA Moderate’ impact category because sensitive financial data is being processed by the system. However, for individuals who are making guest payments where no persistent account is established, the authentication and proofing impact levels may be lower. Agency authorizing officials SHOULD require documentation that demonstrates adherence to the DIRM process as a part of the authority to operate (ATO) for the underlying information system that supports an online service. Agency authorizing officials SHOULD require documentation from CSPs that demonstrates adherence to the DIRM process as part of procurement or ATO processes for integration with CSPs.

These guidelines use the term FISMA impact level; other NIST RMF publications also use the term system impact level to refer to such impact categorization.

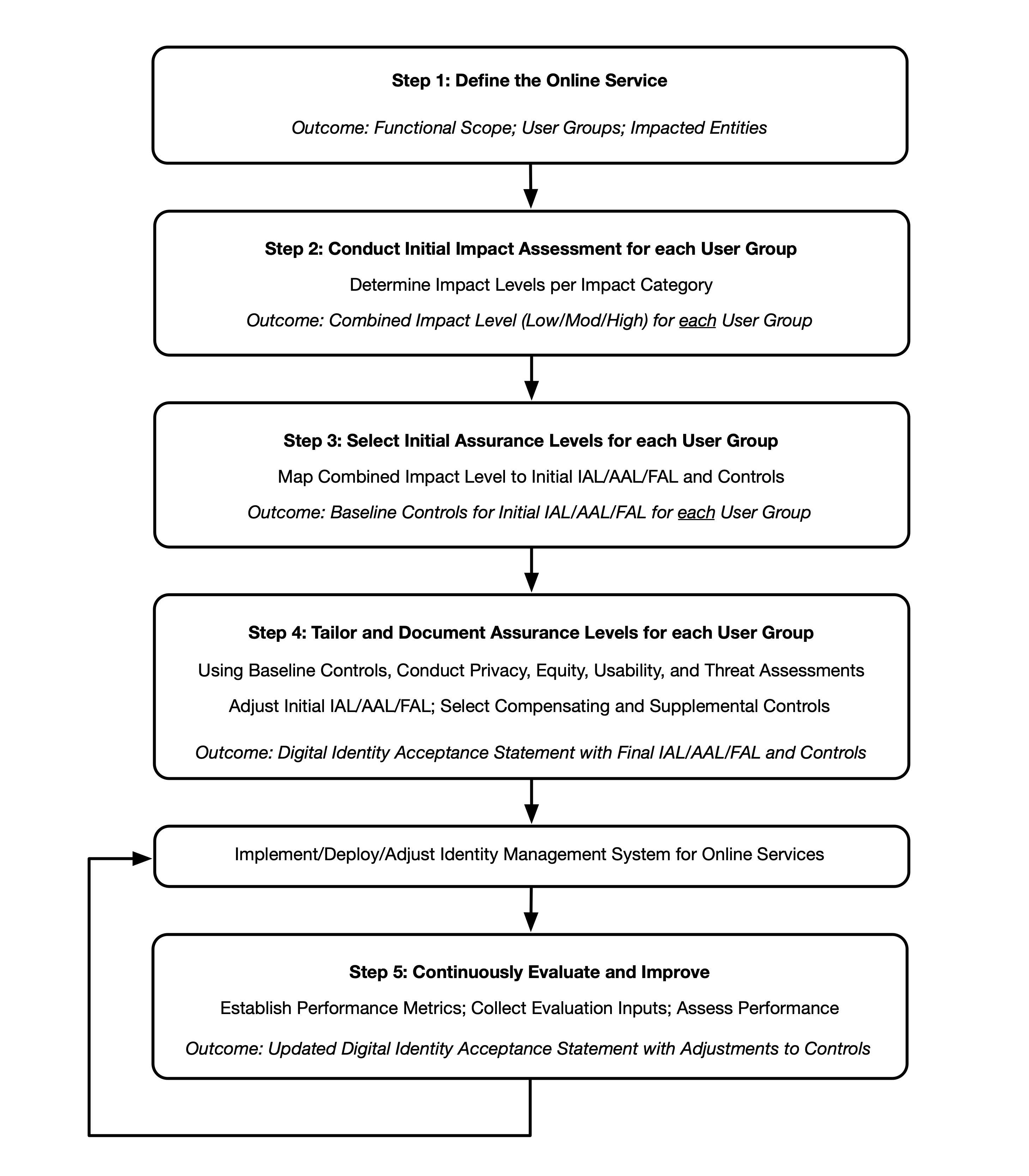

There are 5 steps in the DIRM process:

- Define the online service: As a starting point, the organization documents a description of the online service in terms of its functional scope, the user groups it is intended to serve, the types of online transactions available to each user group, and the underlying data that the online service processes through its interfaces. If the online service is one element of a broader business process, its role is documented, as are the uses of any data collected and processed by the online service. Additionally, an organization needs to determine the entities that will be impacted by the online service and the broader business process of which it is a part. The outcome is a description of the online service, its users, and the entities that may be impacted by its functionality.

- Conduct initial impact assessment: In this step, organizations assess the impacts of a compromise of the online service that might be addressed by an identity system (i.e., identity proofing, authentication, or federation). Each function of the online service is assessed against a defined set of harms and impact categories. Each user group of the online service is considered separately based on the transactions available to that user group (i.e., the permissions that the group is granted relative to the data and functions of the online service). The outcome of this step is a documented set of impact categories and associated impact levels that are determined by considering the transactions available to each user group of the online service.

- Select initial assurance levels: In this step, the impact categories and impact levels are evaluated to determine the initial assurance levels to protect the online service from unauthorized access and fraud. Using the assurance levels, the organization identifies the baseline controls for the IAL, AAL, and FAL for each user group based on the requirements in companion volumes [SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], and [SP800-63C], respectively. The outcome of this step is an identified initial IAL, AAL, and FAL, as applicable, for each user group.

- Tailor and document assurance level determinations: In this step, detailed assessments are conducted or leveraged to determine the potential impact of the initially selected assurance levels and their associated controls on privacy, customer experience, and resistance to the current threat environment. Tailoring may result in a modification of the initially assessed assurance level, the identification of compensating or supplemental controls (see Sec. 3.4.2 and Sec. 3.4.3), or both. All assessments and final decisions are documented and justified. The outcome is a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (see Sec. 3.4.4) with a defined and implementable set of assurance levels and a final set of controls for the online service.

- Continuously evaluate and improve: In this step, information on the performance of the identity management approach is gathered and evaluated. This evaluation considers a diverse set of factors, including business impacts, effects on fraud rates, and impacts on user communities. This information is crucial for determining whether the selected assurance levels and controls meet mission, business, security, and — where applicable — program integrity needs. It also helps monitor for unintended harms that impact privacy and access. Opportunities for improvement should also be considered by closely monitoring the evolving threat landscape and investigating new technologies and methodologies that can counter those threats, improve customer experience, or enhance privacy. The outcomes of this step are performance metrics, documented and transparent processes for evaluation and redress, and ongoing improvements to the identity management approach.

Fig. 6. High-level diagram of the DIRM Process Flow

Figure 6 illustrates the major actions and outcomes for each step of the DIRM process flow. While presented as a stepwise approach, there can be many points in the process that require divergence from the sequential order, including the need for iterative cycles between initial task execution and revisiting tasks. For example, the introduction of new regulations or requirements while an assessment is in progress may require organizations to revisit a step in the process. Additionally, new functionalities, changes in data usage, and changes to the threat environment may require an organization to revisit steps in the DIRM process at any point, including potentially modifying the assurance levels and/or the related controls of the online service.

Organizations SHOULD adapt and modify this overall approach to meet organizational processes, governance, and enterprise risk management practices. At a minimum, organizations SHALL execute and document each step and complete and document the normative mandates and outcomes of each step, regardless of any organization-specific processes or tools used in the overall DIRM process. Additionally, organizations SHOULD consult with a representative sample of the online service’s user population to inform the design and performance evaluation of the identity management system.

Define the Online Service

The purpose of defining the online service is to understand its functionality and establish a common understanding of its context, which will inform subsequent steps of the DIRM process. The role of the online service is contextualized as part of the broader business environment and associated processes, resulting in a documented description of the scope of the online service, user groups and their expectations, data processed, impacted entities, and other pertinent details.

RPs SHALL develop a description of the online service that includes, at minimum:

- The organizational mission and business objectives supported by the online service

- The mission and business partner dependencies associated with the online service

- Legal, regulatory, and contractual requirements, including privacy obligations that apply to the online service

- The functionality of the online service and the data that it is expected to process

- User groups that need to have access to the online service as well as the types of online transactions and access privileges available to each user group

- The set of entities (to include users of the online service, organizations, and populations served) that will be impacted by the online service and the broader business process of which it is a part

- The results of any preexisting DIRM assessments (as an input) and the current state of any preexisting identity technologies (i.e., proofing, authentication, or federation)

- The estimated availability of the types of identity evidence required for identity proofing across all user groups served

It is imperative to consider unexpected and undesirable impacts, as well as the scale of impact, on different entities that result from an unauthorized user gaining access to the online service due to a failure of the digital identity system. For example, if an attacker obtained unauthorized access to an online service that controls a power plant, the actions taken by the bad actor could have devastating environmental impacts on the local populations that live near the facility and cause power outages for the localities served by the plant.

It is important to differentiate between user groups and impacted entities, as described in this document. The online service will allow access to a set of users who may be partitioned into a few user groups based on the kind of functionality that is offered to that user group. For example, an online income tax filing and review service may have the following user groups: (1) citizens who need to check the status of their personal tax returns, (2) tax preparers who file tax returns on behalf of their clients, and (3) system administrators who assign privileges to different groups of users or create new user groups as needed. Impacted entities include all those who could face negative consequences in the event of a digital identity system failure. This will likely include members of the user groups but may also include those who never directly use the system.

Accordingly, the scope of impact assessments SHALL include individuals who use the online application as well as the organization itself. Additionally, organizations SHALL identify other entities (e.g., mission partners, communities, and those identified in [SP800-30]) that need to be specifically included based on mission and business needs. At a minimum, organizations SHALL document all impacted entities (both internal and external to the organization) when conducting their impact assessments.

The output of this step is a documented description of the online service, including a list of the user groups and other entities that are impacted by the functionality provided by the online service. This information will serve as a basis and establish the context for effectively applying the impact assessments detailed in the following sections.

Conduct Initial Impact Assessment

This step of the DIRM process addresses the first dimension of risk by identifying the risks to the online service that might be addressed by an identity system.

The purpose of the initial impact assessment is to identify the potential adverse impacts of failures in identity proofing, authentication, and federation that are specific to an online service, yielding an initial set of assurance levels. RPs SHOULD consider historical data and results from user focus groups when performing this step. The impact assessment SHALL include:

- Identifying a set of impact categories and the potential harms for each impact category,

- Identifying the levels of impact, and

- Assessing the level of impact for each user group.

The level of impact for each user group identified in Sec. 3.1 SHALL be considered separately based on the transactions available to that user group. This gives organizations maximum flexibility in selecting and implementing assurance levels that are appropriate for each user group. While impacts to user groups, the organization, and other entities are primary considerations for impact assessments, organizations SHOULD also consider scale (e.g., number of persons impacted by transactions).

The output of this assessment is a defined impact level (i.e., Low, Moderate, or High) for each user group. This serves as the primary input to the initial assurance level selection.

Identify Impact Categories and Potential Harms

While an online service has a discrete set of users and user groups that authenticate to access the functionality provided by the service, there may be a much larger set of entities that are impacted when imposters and attackers obtain unauthorized access to the online service due to errors in identity proofing, authentication, or federation. In Sec. 3.1, such impacted entities are identified and documented as a part of defining the online service.

In this step, organizations identify the categories of impact that are applicable to the impacted entities for a given online service. At a minimum, organizations SHALL include the following impact categories in their impact assessments:

- Degradation of mission delivery

- Damage to trust, standing, or reputation

- Unauthorized access to information

- Financial loss or liability

- Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health

Organizations SHOULD include additional impact categories, as appropriate, based on their mission and business objectives. Each impact category SHALL be documented and consistently applied when implementing the DIRM process across different online services offered by the organization.

Harms refer to any adverse effects that would be experienced by an impacted entity. They provide a means to effectively understand the impact categories and how they may apply to specific entities impacted by the online service. For each impact category, organizations SHALL consider potential harms for each of the impacted entities identified in Sec. 3.1.

Examples of harms associated with each category include:

- Degradation of mission delivery:

- Harms to individuals may include the inability to access government services or benefits for which they are eligible.

- Harms to the organization (including the organization offering the online service and organizations supported by the online service) may include the inability to perform current mission/business functions in a sufficiently timely manner, with sufficient confidence and/or correctness, or within planned resource constraints, or the inability or limited ability to perform mission/business functions in the future.

- Damage to trust, standing, or reputation:

- Harms to individuals may include damage to image or reputation as a result of impersonation.

- Harms to the organization may include damage to reputation resulting in the fostering of a negative image, the deterioration of existing trust relationships, or the inability to forge potential new trust relationships in the future.

- Unauthorized access to information:

- Harms to individuals may include the breach of personal information or other sensitive information that may result in secondary harms, such as financial loss, loss of life, physical or psychological injury, impersonation, identity theft, or persistent inconvenience.

- Harms to the organization may include the exfiltration, deletion, degradation, or exposure of intellectual property or the unauthorized disclosure of other information assets, such as classified materials or controlled unclassified information (CUI).

- Financial loss or liability:

- Harms to individuals may include debts incurred or assets lost as a result of fraud or other harm, damage to or loss of credit, actual or potential loss of employment or sources of income, loss of housing, and/or other financial loss.

- Harms to the organization may include costs related to fraud or other criminal activity, loss of assets, devaluation, or loss of business.

- Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health:

- Harms to individuals may include death or damage to physical well-being that may result in secondary harms, such as damage to mental or emotional well-being, or impact on environmental health that could result in the uninhabitability of the local environment and require intervention to address potential or actual damage.

- Harms to the organization may include damage to or loss of the organization’s workforce or damage to the surrounding environment and the subsequent impact of unsafe conditions.

The outcome of this activity is a list of impact categories and harms that will be used to assess adverse consequences for impacted entities.

Identify Potential Impact Levels

In this step, the organization assesses the potential level of impact caused by an unauthorized user gaining access to the online service for each of the impact categories selected by the organization (from Sec. 3.2.1). Impact levels are assigned using one of the following potential impact values:

- Low: Expected to have a limited adverse effect

- Moderate: Expected to have a serious adverse effect

- High: Expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect

Each user group can have a distinct set of privileges and functionalities through the online service. Hence, it is necessary to consider the adverse consequences for each set of impacted entities in each of the impact categories, as a result of an intruder obtaining unauthorized access as a member of a particular user group. To provide a more objective basis for impact level assignments, organizations SHOULD develop thresholds and examples for the impact levels for each impact category. Where this is done, particularly with specifically defined quantifiable values, these thresholds SHALL be documented and used consistently in the DIRM assessments across an organization to allow for a common understanding of risks.

Examples of potential impacts in each of the impact categories include:

- Degradation of mission delivery:

- Low: Expected to result in limited mission capability degradation such that the organization is still able to perform its primary functions but with some reduced effectiveness

- Moderate: Expected to result in serious mission capability degradation such that the organization is still able to perform its primary functions but with significantly reduced effectiveness

- High: Expected to result in severe or catastrophic mission capability degradation or loss over a duration such that the organization is unable to perform one or more of its primary functions

- Damage to trust, standing, or reputation:

- Low: Expected to result in limited, short-term inconvenience, distress, or embarrassment to any party

- Moderate: Expected to result in serious short-term or limited long-term inconvenience, distress, or damage to the standing or reputation of any party

- High: Expected to result in severe or serious long-term inconvenience, distress, or damage to the standing or reputation of any party or many individuals

- Unauthorized access to information:

- Low: Expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals, as defined in [FIPS199]

- Moderate: Expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals, as defined in [FIPS199]

- High: Expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals, as defined in [FIPS199]

- Financial loss or financial liability:

- Low: Expected to result in limited financial loss or liability to any party

- Moderate: Expected to result in a serious financial loss or liability to any party

- High: Expected to result in severe or catastrophic financial loss or liability to any party

- Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health:

- Low: Expected to result in a limited impact on human safety or health that resolves on its own or with a minor amount of medical attention or a limited impact on environmental health that requires at most minor intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage

- Moderate: Expected to result in a serious impact on human safety or health that requires significant medical attention, serious impact on environmental health that results in a period of uninhabitability and requires significant intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage, or the compounding impacts of multiple low-impact events

- High: Expected to result in a severe or catastrophic impact on human safety or health, such as severe injury, trauma, or death, a severe or catastrophic impact on environmental health that results in long-term or permanent uninhabitability and requires extensive intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage, or the compounding impacts of multiple moderate impact events

This guideline provides three impact levels. However, organizations MAY define more granular impact levels and develop their own methodologies for their initial impact assessment activities.

Impact Analysis

The impact analysis considers the level of impact (i.e., Low, Moderate, or High) of compromises of any of the identity system functions (i.e., identity proofing, authentication, and federation) that results in an intruder obtaining unauthorized access to the online service as a member of a particular user group, and initiating transactions that cause negative effects on impacted entities. The impact analysis considers the following dimensions:

- User groups (see Sec. 3.1)

- Impacted entities (see Sec. 3.1)

- Impact categories (see Sec. 3.2.1)

- Impact levels (see Sec. 3.2.2)

The impact analysis SHALL consider the level of impact for each impact category for each type of impacted entity if an intruder obtains unauthorized access as a member of each user group. Because different sets of transactions are available to each user group, it is important to consider each user group separately for this analysis.

For example, for an online service that allows for the control, operation, and monitoring of a water treatment facility, each group of users (e.g., technicians who control and operate the facility, auditors and monitoring officials, system administrators) is considered separately based on the transactions available to that user group through the online service. The impact analysis assesses the level of impact (i.e., Low, Moderate or High) on various impacted entities (e.g., citizens who drink the water, the organization that owns the facility, auditors, monitoring officials) for each of the impact categories being considered if a bad actor obtains unauthorized access to the online service as a member of a user group.

The impact analysis SHALL be performed for each user group that has access to the online service. For each impact category, the impact level is estimated for each impacted entity as a result of a compromise of the online service caused by failures in the identity management functions.

If there is no harm or impact for a given impact category for any entity, the impact level can be marked as None.

The output of this impact analysis is a set of impact levels for each user group that SHALL be documented in a suitable format for further analysis in accordance with Sec. 3.4.

Determine the Combined Impact Level for Each User Group

The impact assessment levels for each user group are combined to establish a single impact level to represent the risks to impacted entities from a compromise of identity proofing, authentication, and/or federation functions for that user group.

Organizations can apply a variety of methods for this combinatorial analysis, such as:

- Using a high-water mark approach across the various impact categories and impacted entities to derive the effective impact level

- Assigning different weights to different impact categories and/or impacted entities and taking an average to derive the effective impact level

- Some other combinatorial logic that aligns with the organization’s mission and priorities

Organizations SHALL document the approach they use to combine their impact assessment into an overall impact level for each of their defined user groups and SHALL apply it consistently across all of its online services. At the conclusion of the combinatorial analysis, organizations SHALL document the impact for each user group.

The outcome of this step is an effective impact level for each user group due to a compromise of the identity management system functions (i.e., identity proofing, authentication, federation).

Select Initial Assurance Levels and Baseline Controls

The effective impact level (i.e., Low, Moderate, or High) serves as a primary input to the process of selecting the initial assurance level for each user group (see Sec. 3.3.1) to identify the corresponding set of baseline digital identity controls from the requirements and guidelines in the companion volumes [SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], and [SP800-63C]. The resulting initial assurance level for each user group applies to all three digital identity system functions (i.e., identity proofing, authentication, and federation).

The initial set of selected digital identity controls and processes will be assessed and tailored in Step 4 based on potential risks generated by the identity management system.

Assurance Levels

Depending on the functionality and deployed architecture of the online service, the support of one or more of the identity management functions (i.e., identity proofing, authentication, and federation) may be required. The strength of these functions is described in terms of assurance levels. The RP SHALL identify the types of assurance levels that apply to their online service from the following:

- IAL: The robustness of the identity proofing process to determine the identity of an individual. The IAL is selected to mitigate risks that result from potential identity proofing failures.

- AAL: The robustness of the authentication process itself and the binding between an authenticator and a specific individual’s identifier. The AAL is selected to mitigate risks that result from potential authentication failures.

- FAL: The robustness of the federation process used to communicate authentication and attribute information to an RP from an IdP. The FAL is selected to mitigate risks that result from potential federation failures.

Assurance Level Descriptions

A summary of each of the xALs is provided below. While high-level descriptions of the assurance levels are provided in this subsection, readers of this guideline are encouraged to refer to companion volumes [SP800-63A], [SP800-63B], and [SP800-63C] for normative guidelines and requirements for each assurance level.

Identity Assurance Level

-

IAL1: IAL1 supports the real-world existence of the claimed identity and provides some assurance that the applicant is associated with that identity. Core attributes are obtained from identity evidence or self-asserted by the applicant. All core attributes are validated against authoritative or credible sources, and steps are taken to link the attributes to the person undergoing the identity proofing process.

-

IAL2: IAL2 requires collecting additional evidence and a more rigorous process for validating the evidence and verifying the identity.

-

IAL3: IAL3 adds the requirement for a trained CSP representative (i.e., proofing agent) to interact directly with the applicant, as part of an on-site attended identity proofing session, and the collection of at least one biometric.

Table 1 describes the control objectives (i.e., attack protections) for each identity assurance level.

| IAL | Control Objectives | User Profile |

|---|---|---|

| IAL1 | Limit highly scalable attacks. Protect against synthetic identity. Protect against attacks that use compromised personal information. | Access to personal information is required but limited. User actions are limited (e.g., viewing and making modifications to individual personal information). Fraud cannot be directly perpetrated through available user functions. Users cannot receive payments until an offline or manual process is conducted. |

| IAL2 | Limit scaled and targeted attacks. Protect against basic evidence falsification and theft. Protect against basic social engineering. | Users can view and change financial information (e.g., a direct deposit location). Individuals can directly perpetrate financial fraud through the available application functionality. A user can view or modify other users’ personal information. Users have visibility into or access to proprietary information. |

| IAL3 | Limit sophisticated attacks. Protect against advanced evidence falsification, theft, and repudiation. Protect against advanced social engineering attacks. | Users have direct access to multiple highly sensitive records; administrator access to servers, systems, or security data; the ability to access large sets of data that may reveal sensitive information about one or many users; or access that could result in a breach that would constitute a major incident under OMB guidance. |

Authentication Assurance Level

-

AAL1: AAL1 provides basic confidence that the claimant controls an authenticator that is bound to the subscriber account. AAL1 requires either single-factor or multi-factor authentication using a wide range of available authentication technologies. Verifiers are expected to make multi-factor authentication options available at AAL1 and encourage their use. Successful authentication requires the claimant to prove possession and control of the authenticator through a secure authentication protocol.

-