Usability Considerations

This section is informative.

To align with the standard terminology of user-centered design and usability, the term “user” is used throughout this section to refer to the human party. In most cases, the user in question will be the subject in the role of applicant, claimant, or subscriber, as described elsewhere in these guidelines.

[ISO/IEC9241-11] defines usability as the “extent to which a system, product, or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.” This definition focuses on users, their goals, and the contexts of use as the key elements necessary for achieving effectiveness, efficiency, satisfaction, and usability.

A user’s goal when accessing an information system is to perform an intended task. Authentication is the function that enables this goal. However, from the user’s perspective, authentication stands between them and their intended task. Effective design and implementation of the authentication process makes it easy to do the right thing, hard to do the wrong thing, and easy to recover if the wrong thing happens.

Organizations need to be cognizant of the overall implications of their stakeholders’ entire digital authentication ecosystem. Users often employ multiple authenticators, each for a different RP. They then struggle to remember passwords, recall which authenticator goes with which RP, and carry multiple physical authentication devices. Evaluating the usability of authentication is critical, as poor usability often results in coping mechanisms and unintended workarounds that can ultimately degrade the effectiveness of security controls.

Integrating usability into the development process can lead to authentication solutions that are secure and usable while still addressing users’ authentication needs and organizations’ business goals. The impacts of usability across digital systems needs to be considered as part of the risk assessment when deciding on the appropriate AAL. Authenticators with a higher AAL sometimes offer better usability and should be allowed for use with lower AAL applications.

Leveraging federation for authentication can alleviate many usability issues, though such an approach has its tradeoffs, as discussed in [SP800-63C].

This section provides general usability considerations and possible implementations but does not recommend specific solutions. The implementations mentioned are examples that encourage innovative technological approaches to address specific usability needs. Furthermore, usability considerations and their implementations are sensitive to many factors that prevent a one-size-fits-all solution. For example, a font size that works in a desktop computing environment may force text to scroll off of a small OTP authenticator screen. Performing a usability evaluation on the selected authenticator is a critical component of implementation. It is important to conduct evaluations with representative users, set realistic goals and tasks, and identify appropriate contexts of use.

Guidelines and considerations are described from the users’ perspective.

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 [Section508] was enacted to eliminate barriers in information technology and require federal agencies to make electronic and information technology accessible to people with disabilities. While these guidelines do not directly assert requirements from Section 508, identity service providers are expected to comply with Section 508 provisions. Beyond compliance with Section 508, federal agencies and their service providers are generally expected to design services and systems with the experiences of people with disabilities in mind to ensure that accessibility is prioritized throughout identity system lifecycles.

Common Usability Considerations for Authenticators

When selecting and implementing an authentication system, consider usability across the entire lifetime of the selected authenticators (e.g., their typical use and intermittent events) while being mindful of users, their goals, and their contexts of use.

A single authenticator type does not usually suffice for the entire user population. Therefore, whenever possible and based on AAL requirements, CSPs should support alternative authenticator types and allow users to choose the type that best meets their needs. Task immediacy, perceived cost-benefit trade-offs, and unfamiliarity with certain authenticators often impact choices. Users tend to choose options that incur the least burden or cost at that moment. For example, if a task requires immediate access to an information system, a user may prefer to create a new subscriber account and password rather than select an authenticator that requires more steps. Alternatively, users may choose a federated identity option that is approved at the appropriate IAL, AAL, and FAL if they already have a subscriber account with an identity provider. Users may understand some authenticators better than others and have different levels of trust based on their understanding and experience.

Positive user authentication experiences are integral to achieving desired business outcomes. Therefore, organizations should strive to consider authenticators from the users’ perspective. The overarching authentication usability goal is to minimize user burden and authentication friction (e.g., the number of times a user has to authenticate, the steps involved, and the amount of information they have to track). Single sign-on exemplifies one such minimization strategy.

Usability considerations applicable to most authenticators are described below. Subsequent sections describe usability considerations specific to a particular authenticator.

Usability considerations that are applicable to most authenticators include:

-

Provide information on the use and maintenance of the authenticator (e.g., what to do if the authenticator is lost or stolen), and instructions for use, especially if there are different requirements for first-time use or initialization.

-

Authenticator availability, as users will need to remember to have their authenticator readily available. Consider the need for alternative authentication options to protect against loss, damage, or other negative impacts on the original authenticator and the potential loss of battery power, if applicable.

-

Alternative authentication options whenever possible and based on AAL requirements. This allows users to choose an authenticator based on their context, goals, and tasks (e.g., the frequency and immediacy of the task). Alternative authentication options also help address availability issues that may occur with a particular authenticator.

- Characteristics of user-facing text:

- Write user-facing text (e.g., instructions, prompts, notifications, error messages) in plain language for the intended audience. Avoid technical jargon, and write for the audience’s expected literacy level.

- Consider the legibility of user-facing and user-entered text, including font style, size, color, and contrast with the surrounding background. Illegible text contributes to user entry errors. To enhance legibility, consider the use of:

- High contrast (i.e., black on white)

- Sans serif fonts for electronic displays and serif fonts for printed materials.

- Fonts that clearly distinguish between characters that are easily confused (e.g., the capital letter “O” and the number zero “0”)

- A minimum font size of 12 points as long as the text fits for display on the device

- Avoid using icons (e.g., padlocks or shields) that might be confused with security indicators in browsers.

- User experience during authenticator entry:

- Offer the option to display text during entry, as masked text entry is error-prone. Once a given character is displayed long enough for the user to see, it can be hidden. Consider the device when determining masking delay time, as it takes longer to enter passwords on mobile devices (e.g., tablets and smartphones) than on traditional desktop computers. Ensure that masking delay durations are consistent with user needs.

- Ensure that the time allowed for text entry is adequate (i.e., the entry screen does not time out prematurely). Ensure that the allowed text entry times are consistent with user needs.

- Provide clear, meaningful, and actionable feedback on entry errors to reduce user confusion and frustration. Significant usability implications arise when users do not know that they have entered text incorrectly.

- Allow at least 10 entry attempts for authenticators that require the entry of the authenticator output by the user. The longer and more complex the entry text, the greater the likelihood of user entry errors.

- Provide clear, meaningful feedback on the number of remaining allowed attempts. For rate limiting (i.e., throttling), inform users how long they have to wait until the next attempt.

- Minimize the impact of form-factor constraints, such as limited touch and display areas on mobile devices:

- Larger touch areas improve usability for text entry since typing on small devices is significantly more error-prone and time-consuming than typing on a full-size keyboard due to the size of the input mechanism (e.g., a finger) relative to the size of the on-screen target.

- Follow good user interface and information design for small displays.

Usability considerations for intermittent events (e.g., reauthentication, subscriber account lock-out, expiration, revocation, damage, loss, theft, and non-functional software) across authenticator types include:

-

Prompt users to perform some activity just before (e.g., two minutes before) an inactivity timeout would otherwise occur.

-

Prompt users to save their work before a fixed reauthentication timeout occurs regardless of user activity.

-

Clearly communicate how and where to acquire technical assistance (e.g., provide users with a link to an online self-service feature, chat sessions, or a phone number for help desk support). Ideally, sufficient information can be provided to enable users to recover from intermittent events on their own without outside intervention.

-

Provide an accessible means for the subscriber to end their session (i.e., logoff).

Usability Considerations by Authenticator Type

The following sections describe other usability considerations that are specific to particular authenticator types.

Passwords

Typical Usage

Users often manually input the password (sometimes referred to as a passphrase or PIN). Alternatively, they may use a password manager to assist in the selection of a secure password and in maintaining distinct passwords for each authenticated service. The use of distinct passwords is important to avoid “password stuffing” attacks in which an attacker uses a compromised password from one site on other sites where the user might also have an account. Agencies should carefully evaluate password managers before making recommendations or mandates to confirm that they meet expectations for secure implementation.

Usability considerations for typical usage without a password manager include:

- Memorability of the password

- The likelihood of a recall failure increases as there are more items for users to remember. With fewer passwords, users can more easily recall the specific password needed for a particular RP.

- The memory burden is greater for a less frequently used password.

- User experience during entry of the password

- Support copy and paste functionality in fields for entering passwords, including passphrases.

Intermittent Events

Usability considerations for intermittent events include:

- When users create and change passwords

- Clearly communicate information on how to create and change passwords.

- Clearly communicate password requirements, as specified in Sec. 3.1.1.

- Allow at least 64 characters in length to support the use of passphrases. Encourage users to make passwords as lengthy as they want and use any characters that they like (including spaces) to aid memorization. Ensure that user interfaces support sufficient password lengths.

- Do not impose other composition rules (e.g., mixtures of different character types) on passwords.

- Do not require that passwords be changed arbitrarily (e.g., periodically) unless there is a user request or evidence of authenticator compromise (see Sec. 3.1.1 for additional information).

- Provide clear, meaningful, and actionable feedback when chosen passwords are rejected (e.g., when it appears on a “blocklist” of unacceptable passwords or has been used previously).

Look-Up Secrets

Typical Usage

Subscribers use a printed or electronic authenticator to look up the appropriate secrets needed to respond to a verifier’s prompt. For example, a user may be asked to provide a specific subset of the numeric or character strings printed on a card in table format.

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

- User experience during entry of look-up secrets.

- Consider the complexity and size of the prompts. There are greater usability implications with larger subsets of secrets that a user is prompted to look up. Both the cognitive workload and physical difficulty for entry should be taken into account.

Out-of-Band

Typical Usage

Out-of-band authentication requires that users have access to a primary and secondary communication channel.

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

-

Notify users of the receipt of a secret on a lockable device. If the out-of-band device is locked, authentication to the device should be required to access the secret.

-

Depending on the implementation, consider form-factor constraints, which are particularly problematic when users must enter text on mobile devices. Providing larger touch areas will improve usability for entering secrets on mobile devices.

-

Consider offering features that do not require text entry on mobile devices (e.g., a copy-paste feature), which are particularly helpful when the primary and secondary channels are on the same device. For example, it is difficult for users to transfer the authentication secret manually using a smartphone because they must switch back and forth — potentially multiple times — between the out-of-band application and the primary channel.

-

Messages and notifications to out-of-band devices should contain contextual information for the user, such as the name of the service being accessed.

-

Out-of-band messages should be delivered in a consistent manner and style to aid the subscriber in identifying potentially suspicious authentication requests.

Single-Factor OTP

Typical Usage

Users access the OTP generated by the single-factor OTP authenticator. The authenticator output is typically displayed on the authenticator, and the user enters it during the session being authenticated.

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

-

Authenticator output allows at least one minute between changes but ideally allows users two full minutes, as specified in Sec. 3.1.4.1. Users need adequate time to enter the authenticator output, including looking back and forth between the single-factor OTP authenticator and the entry screen.

-

Depending on the implementation, the following are additional usability considerations for implementers:

- It is preferable for the single-factor OTP authenticator to supply its output via an electronic interface (e.g., USB port) so that users do not have to manually enter the authenticator output. However, if a physical input (e.g., pressing a button) is required to operate, the location of the USB ports could pose usability difficulties. For example, the USB ports of some computers are located on the back of the computer and may be difficult for users to reach.

- Limited availability of a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port) could pose usability difficulties. For example, the number of USB ports on laptop computers is often very limited. This may force users to unplug other USB peripherals to use the single-factor OTP authenticator.

Multi-Factor OTP

Typical Usage

Users access the OTP generated by the multi-factor OTP authenticator through a second authentication factor. The OTP is typically displayed on the device, and the user manually enters it during the session being authenticated. The second authentication factor may be achieved through some kind of integral entry pad to enter a password, an integral biometric (e.g., fingerprint) reader, or a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port). Usability considerations for the additional factor also apply (see Sec. 8.2.1 for passwords and Sec. 8.4 for biometrics used in multi-factor authenticators).

\clearpage

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

- User experience during manual entry of the authenticator output

- For time-based OTP, provide a grace period in addition to the time during which the OTP is displayed. Users need adequate time to enter the authenticator output, including looking back and forth between the multi-factor OTP authenticator and the entry screen.

- Consider form-factor constraints if users must unlock the multi-factor OTP authenticator via an integral entry pad or enter the authenticator output on mobile devices. Typing on small devices is significantly more error-prone and time-consuming than typing on a traditional keyboard. Providing larger touch areas improves usability for unlocking the multi-factor OTP authenticator or entering the authenticator output on mobile devices.

- Limited availability of a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port) could pose usability difficulties. For example, laptop computers often have a limited number of USB ports, which may force users to unplug other USB peripherals to use the multi-factor OTP authenticator.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Authenticator

Typical Usage

Users authenticate by proving possession and control of the cryptographic key.

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

-

Give cryptographic keys appropriately descriptive names that are meaningful to users so that they can recognize and recall which cryptographic key to use for which authentication task. This prevents users from having to deal with multiple similarly and ambiguously named cryptographic keys. Selecting from multiple cryptographic keys on smaller mobile devices may be particularly problematic if the names of the cryptographic keys are shortened due to reduced screen sizes.

-

Requiring a physical input (e.g., pressing a button) to operate a single-factor cryptographic authenticator could pose usability difficulties. For example, some USB ports are located on the back of computers, making it difficult for users to reach the port.

-

For connected authenticators, the limited availability of a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port) could pose usability difficulties. For example, laptop computers often have a limited number of USB ports, which may force users to unplug other USB peripherals to use the authenticator.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Authenticator

Typical Usage

To authenticate, users prove possession and control of the cryptographic key and control of the activation factor. Usability considerations for the additional factor also apply (see Sec. 8.2.1 for passwords and Sec. 8.4 for biometrics used as activation factors).

Usability considerations for typical usage include:

-

Give cryptographic keys appropriately descriptive names that are meaningful to users so that they can recognize and recall which cryptographic key to use for which authentication task. This prevents users from having to deal with multiple similarly and ambiguously named cryptographic keys. Selecting from multiple cryptographic keys on smaller mobile devices may be particularly problematic if the names of the cryptographic keys are shortened due to reduced screen sizes.

- Do not require users to keep external multi-factor cryptographic authenticators connected following authentication. Users may forget to disconnect the authenticator when they are done with it (e.g., forgetting a smartcard in the smartcard reader and walking away from the computer).

- Users need to be informed about whether the authenticator is required to stay connected or not.

- For connected authenticators, the limited availability of a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port) could pose usability difficulties. For example, laptop computers often have a limited number of USB ports, which may force users to unplug other USB peripherals to use the authenticator.

Summary of Usability Considerations

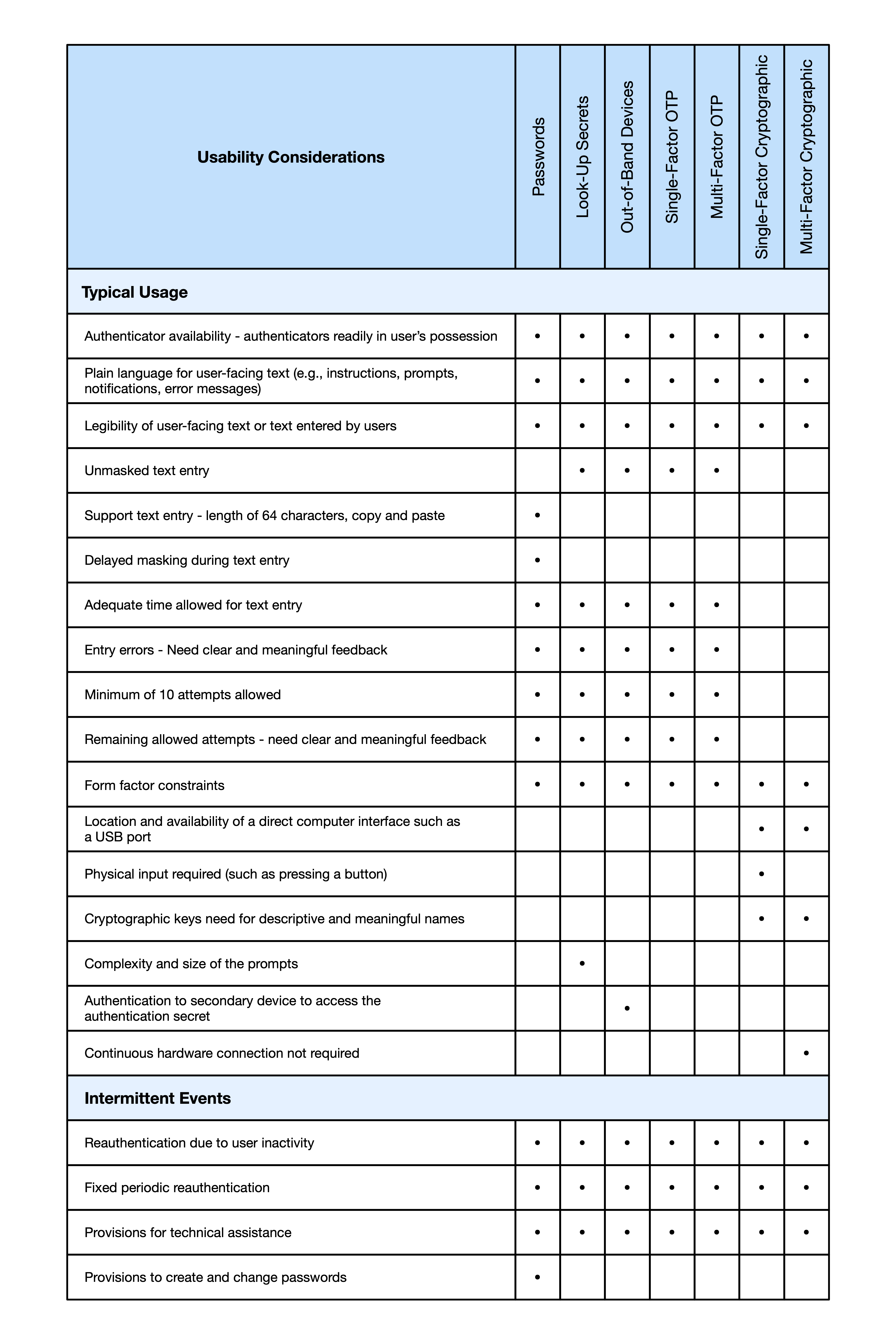

Figure 4 summarizes the usability considerations for typical usage and intermittent events for each authenticator type. Many of the usability considerations for typical usage apply to most of the authenticator types, as demonstrated in the rows. The table highlights common and divergent usability characteristics across the authenticator types. Each column allows readers to easily identify the usability attributes to address for each authenticator. Depending on the users’ goals and context of use, certain attributes may be valued over others. Whenever possible, provide alternative authenticator types, and allow users to choose between them.

Multi-factor authenticators (e.g., multi-factor OTPs and multi-factor cryptographic) also inherit their activation factor’s usability considerations. As biometrics are only allowed as an activation factor in multi-factor authentication solutions, usability considerations for biometrics are not included in Fig. 4 and are discussed in Sec. 8.4.

Fig. 4 Usability considerations by authenticator type

Usability Considerations for Biometrics

This section provides a high-level overview of general usability considerations for biometrics. A more detailed discussion of biometric usability can be found in Usability & Biometrics, Ensuring Successful Biometric Systems [UsabilityBiometrics].

User familiarity and practice with the device improve performance for all modalities. Device affordances (i.e., properties of a device that allow a user to perform an action), feedback, and clear instructions are critical to a user’s success with the biometric device. For example, provide clear instructions on the required actions for liveness detection. Ideally, users can select the modality that they are most comfortable with for their second authentication factor. Various user populations may be more comfortable, familiar with, and accepting of some biometric modalities than others. Additionally, user experience with biometrics is an activation factor. Provide clear, meaningful feedback on the number of remaining allowed attempts. For example, for rate limiting (i.e., throttling), inform users of the time period they have to wait until their next attempt.

Typical Usage

The three biometric modalities that are most commonly used for authentication are fingerprint, face, and iris.

- Fingerprint usability considerations:

- Users have to remember which fingers they used for initial enrollment.

- The amount of moisture on the finger affects the sensor’s ability for successful capture.

- Additional factors that influence fingerprint capture quality include age, gender, and occupation (e.g., users who handle chemicals or work extensively with their hands may have degraded friction ridges).

- Face usability considerations:

- Users have to remember whether they wore any artifacts (e.g., glasses) during enrollment, which affects facial recognition accuracy.

- Differences in environmental lighting conditions may affect facial recognition accuracy.

- Facial expressions affect facial recognition accuracy (e.g., smiling versus a neutral expression).

- Facial poses affect facial recognition accuracy (e.g., looking down or away from the camera).

- Iris usability considerations:

- Wearing colored contacts may affect iris recognition accuracy.

- Users who have had eye surgery may need to re-enroll after surgery.

- Differences in environmental lighting conditions may affect iris recognition accuracy, especially for certain iris colors.

Intermittent Events

Since biometrics are only permitted as a second factor for multi-factor authentication, usability considerations for intermittent events with the primary factor still apply. Intermittent events that may affect recognition accuracy using biometrics include:

- Degraded fingerprints or finger injuries

- Dirty, dry, or wet hands; wearing gloves; or wearing a mask

- Natural facial or weight changes over time

- Eye surgery

Across all biometric modalities, usability considerations for intermittent events include:

- An alternative authentication method must be readily available and clearly communicated. Users should never be required to attempt biometric authentication and should be permitted to use a password as an alternative second factor.

- There should be provisions for technical assistance:

- Clearly communicate information on how and where to acquire technical assistance. For example, provide users with a link to an online self-service feature or a phone number for help desk support. Ideally, provide sufficient information to enable users to recover from intermittent events on their own without outside intervention.

- Inform users of factors that may affect the sensitivity of the biometric sensor (e.g., cleanliness of the sensor).