Authenticator and Verifier Requirements

This section is normative.

This section provides the detailed requirements specific to each type of authenticator. With the exception of reauthentication requirements specified in Sec. 4 and the requirement for phishing resistance at AAL3 described in Sec. 5.2.5, the technical requirements for each of the authenticator types are the same regardless of the AAL at which the authenticator is used.

Requirements by Authenticator Type

Memorized Secrets

A Memorized Secret authenticator — commonly referred to as a password or, if numeric, a PIN — is a secret value intended to be chosen and memorized by the user. Memorized secrets need to be of sufficient complexity and secrecy that it would be impractical for an attacker to guess or otherwise discover the correct secret value. A memorized secret is something you know.

The requirements in this section apply to centrally verified memorized secrets that are used as an independent authentication factor, sent over an authenticated protected channel to the verifier of a CSP. Memorized secrets that are used locally by a multi-factor authenticator are referred to as activation secrets and discussed in Sec. 5.2.11.

Memorized Secret Authenticators

Memorized secrets SHALL be at least 8 characters in length. Memorized secrets SHALL be either chosen by the subscriber or assigned randomly by the CSP.

If the CSP disallows a chosen memorized secret because it is on a blocklist of commonly used, expected, or compromised values (see Sec. 5.1.1.2), the subscriber SHALL be required to choose a different memorized secret. No other complexity requirements for memorized secrets SHALL be imposed. A rationale for this is presented in Appendix A Strength of Memorized Secrets.

Memorized Secret Verifiers

Verifiers SHALL require memorized secrets to be at least 8 characters in length. Verifiers SHOULD permit memorized secrets to be at least 64 characters in length. All printing ASCII [RFC20] characters as well as the space character SHOULD be acceptable in memorized secrets. Unicode [ISO/ISC 10646] characters SHOULD be accepted as well. Verifiers MAY make allowances for likely mistyping, such as removing leading and trailing whitespace characters prior to verification or allowing verification of memorized secrets with differing case for the leading character, provided memorized secrets remain at least 8 characters in length after such processing.

Verifiers SHALL verify the entire submitted memorized secret (i.e., not truncate the secret). For purposes of the above length requirements, each Unicode code point SHALL be counted as a single character.

If Unicode characters are accepted in memorized secrets, the verifier SHOULD apply the normalization process for stabilized strings using either the NFKC or NFKD normalization defined in Sec. 12.1 of Unicode Normalization Forms [UAX15]. This process is applied before hashing the byte string representing the memorized secret. Subscribers choosing memorized secrets containing Unicode characters SHOULD be advised that some characters may be represented differently by some endpoints, which can affect their ability to authenticate successfully.

Memorized secret verifiers SHALL NOT permit the subscriber to store a hint that is accessible to an unauthenticated claimant. Verifiers SHALL NOT prompt subscribers to use specific types of information (e.g., “What was the name of your first pet?”, a technique known as knowledge-based authentication (KBA) or security questions) when choosing memorized secrets.

When processing requests to establish and change memorized secrets, verifiers SHALL compare the prospective secrets against a blocklist that contains values known to be commonly used, expected, or compromised. For example, the list MAY include, but is not limited to:

- Passwords obtained from previous breach corpuses.

- Dictionary words.

- Repetitive or sequential characters (e.g. ‘aaaaaa’, ‘1234abcd’).

- Context-specific words, such as the name of the service, the username, and derivatives thereof.

If the chosen secret is found in the blocklist, the CSP or verifier SHALL advise the subscriber that they need to select a different secret, SHALL provide the reason for rejection, and SHALL require the subscriber to choose a different value. Since the blocklist is used to defend against brute-force attacks and unsuccessful attempts are rate limited as described below, the blocklist SHOULD be of a size sufficient to prevent subscribers from choosing memorized secrets that attackers are likely to guess before reaching the attempt limit. Excessively large blocklists SHOULD NOT be used because they frustrate subscribers’ attempts to establish an acceptable memorized secret and do not provide significantly improved security.

Verifiers SHALL offer guidance to the subscriber to assist the user in choosing a strong memorized secret. This is particularly important following the rejection of a memorized secret on the above list as it discourages trivial modification of listed (and likely very weak) memorized secrets [Blocklists].

Verifiers SHALL implement a rate-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of failed authentication attempts that can be made on the subscriber account as described in Sec. 5.2.2.

Verifiers SHALL NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types or prohibiting consecutively repeated characters) for memorized secrets. Verifiers SHALL NOT require users to periodically change memorized secrets. However, verifiers SHALL force a change if there is evidence of compromise of the authenticator.

Verifiers SHALL allow the use of password managers. To facilitate their use, verifiers SHOULD permit claimants to use “paste” functionality when entering a memorized secret. Password manangers may increase the likelihood that users will choose stronger memorized secrets.

In order to assist the claimant in successfully entering a memorized secret, the verifier SHOULD offer an option to display the secret — rather than a series of dots or asterisks — while it is entered and until it is submitted to the verifier. This allows the claimant to confirm their entry if they are in a location where their screen is unlikely to be observed. The verifier MAY also permit the claimant’s device to display individual entered characters for a short time after each character is typed to verify correct entry. This is common on mobile devices.

The verifier SHALL use approved encryption and an authenticated protected channel when requesting memorized secrets in order to provide resistance to eavesdropping and adversary-in-the-middle attacks.

Verifiers SHALL store memorized secrets in a form that is resistant to offline attacks. Memorized secrets SHALL be salted and hashed using a suitable password hashing scheme. Password hashing schemes take a password, a salt, and a cost factor as inputs and generate a password hash. Their purpose is to make each password guess more expensive for an attacker who has obtained a hashed password file and thereby make the cost of a guessing attack high or prohibitive. A function that is both memory-hard and compute-hard SHOULD be used because it increases the cost of an attack. While NIST has not published guidelines on specific password hashing schemes, examples of such functions include Argon2 [Argon2] and scrypt [Scrypt]. Examples of approved one-way functions include Keyed Hash Message Authentication Code (HMAC) [FIPS198-1], any approved hash function in [SP800-107], Secure Hash Algorithm 3 (SHA-3) [FIPS202], CMAC [SP800-38B], Keccak Message Authentication Code (KMAC), Customizable SHAKE (cSHAKE), and ParallelHash [SP800-185]. The chosen output length of the password hashing scheme SHOULD be the same as the length of the underlying one-way function output.

The salt SHALL be at least 32 bits in length and be chosen arbitrarily so as to minimize salt value collisions among stored hashes. Both the salt value and the resulting hash SHALL be stored for each memorized secret authenticator.

For the Password-based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2) [SP800-132], the cost factor is an iteration count: the more times the PBKDF2 function is iterated, the longer it takes to compute the password hash. Therefore, the iteration count SHOULD be as large as verification server performance will allow, typically at least 10,000 iterations.

In addition, verifiers SHOULD perform an additional iteration of a keyed hashing or encryption operation using a secret key known only to the verifier. This key value, if used, SHALL be generated by an approved random bit generator [SP800-90Ar1] and provide at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of NIST SP 800-131A, Transitioning the Use of Cryptographic Algorithms and Key Lengths [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). The secret key value SHALL be stored separately from the hashed memorized secrets (e.g., in a specialized device like a hardware security module). With this additional iteration, brute-force attacks on the hashed memorized secrets are impractical as long as the secret key value remains secret.

Look-Up Secrets

A look-up secret authenticator is a physical or electronic record that stores a set of secrets shared between the claimant and the CSP. The claimant uses the authenticator to look up the appropriate secrets needed to respond to a prompt from the verifier. For example, the verifier could ask a claimant to provide a specific subset of the numeric or character strings printed on a card in table format. A common application of look-up secrets is the use of one-time “recovery keys” stored by the subscriber for use in the event another authenticator is lost or malfunctions. A look-up secret is something you have.

Look-Up Secret Authenticators

CSPs creating look-up secret authenticators SHALL use an approved random bit generator [SP800-90Ar1] to generate the list of secrets and SHALL deliver the authenticator securely to the subscriber. Look-up secrets SHALL have at least 20 bits of entropy.

Look-up secrets MAY be distributed by the CSP in person, by postal mail to the subscriber’s address of record, or by online distribution. If distributed online, look-up secrets SHALL be distributed over a secure channel in accordance with the post-enrollment binding requirements in Sec. 6.1.2.

If the authenticator uses look-up secrets sequentially from a list, the subscriber MAY dispose of used secrets, but only after a successful authentication.

Look-Up Secret Verifiers

Verifiers of look-up secrets SHALL prompt the claimant for the next secret from their authenticator or for a specific (e.g., numbered) secret. A given secret from an authenticator SHALL be used successfully only once. If the look-up secret is derived from a grid card, each cell of the grid SHALL be used only once.

Verifiers SHALL store look-up secrets in a form that is resistant to offline attacks. Look-up secrets having at least 112 bits of entropy SHALL be hashed with an approved one-way function as described in Sec. 5.1.1.2. Look-up secrets with fewer than 112 bits of entropy SHALL be salted and hashed using a suitable password hashing scheme, also described in Sec. 5.1.1.2. The salt value SHALL be at least 32 bits in length and arbitrarily chosen so as to minimize salt value collisions among stored hashes. Both the salt value and the resulting hash SHALL be stored for each look-up secret.

For look-up secrets that have less than 64 bits of entropy, the verifier SHALL implement a rate-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of failed authentication attempts that can be made on the subscriber account as described in Sec. 5.2.2.

The verifier SHALL use approved encryption and an authenticated protected channel when requesting look-up secrets in order to provide resistance to eavesdropping and AitM attacks.

Out-of-Band Devices

An out-of-band authenticator is a physical device that is uniquely addressable and can communicate securely with the verifier over a distinct communications channel, referred to as the secondary channel. The device is possessed and controlled by the claimant and supports private communication over this secondary channel, separate from the primary channel for authentication. An out-of-band authenticator is something you have.

Out-of-band authentiction uses a short-term secret generated by the verifier. The secret’s purpose is to securely bind the authentication operation on the primary and secondary channel and establishes the claimant’s control of the out-of-band device.

The out-of-band authenticator can operate in one of the following ways:

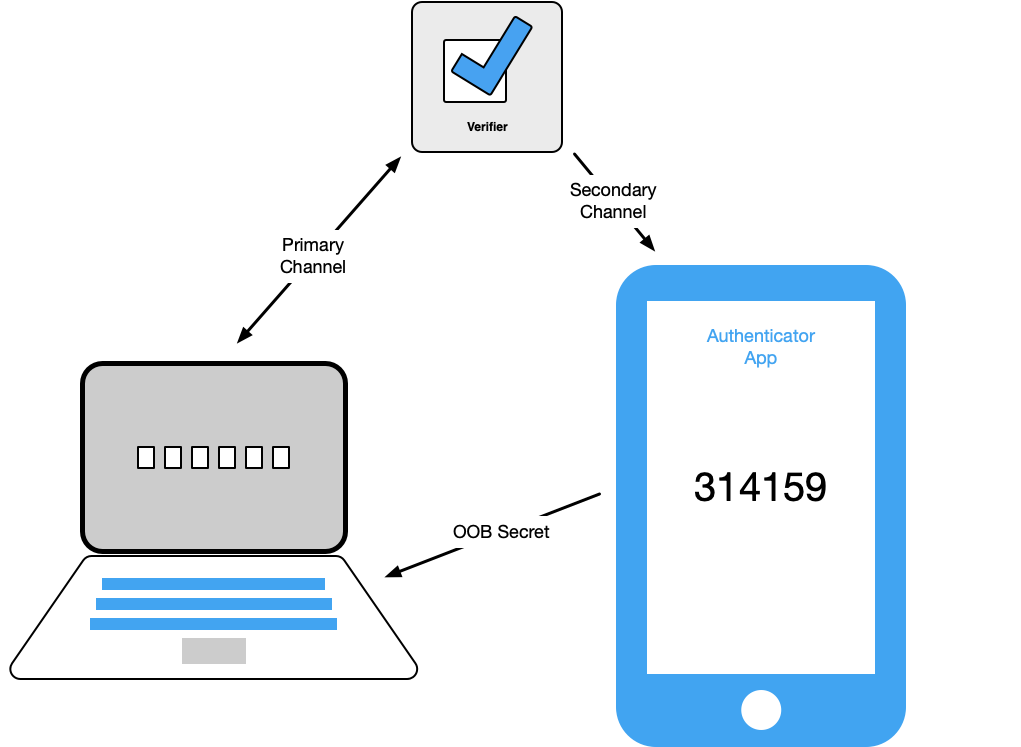

- The claimant transfers a secret received by the out-of-band device via the secondary channel to the verifier using the primary channel. For example, the claimant may receive the secret (typically a 6-digit code) on their mobile device and type it into their authentication session. This method is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Transfer of Secret to Primary Device

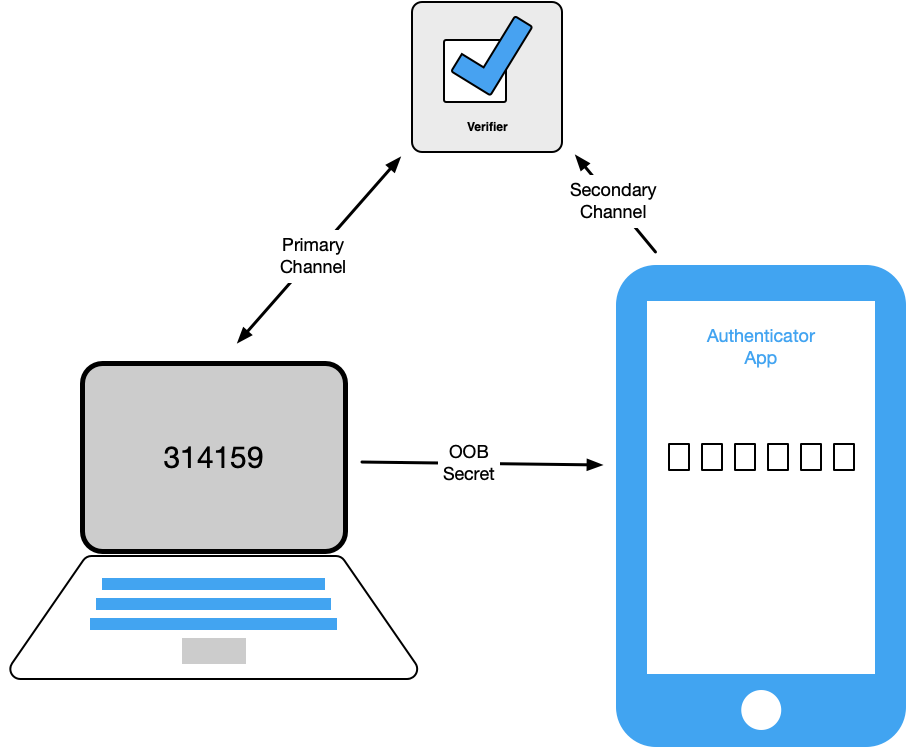

- The claimant transfers a secret received via the primary channel to the out-of-band device for transmission to the verifier via the secondary channel. For example, the claimant may view the secret on their authentication session and either type it into an app on their mobile device or use a technology such as a barcode or QR code to effect the transfer. This method is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Transfer of Secret to Out-of-band Device

Note: A third method of out-of-band authentication involving the comparison of secrets received from the primary and secondary channels and approving on the secondary channel is no longer considered acceptable because it was rarely implemented as described. It raised the likelihood that the claimant would just approve without actually comparing the secrets. For example, an authenticator that receives a push notification from the verifier and simply asks the claimant to approve the transaction (even if providing some additional information about the authentication) does not meet the requirements of this section.

Out-of-Band Authenticators

The out-of-band authenticator SHALL establish a separate channel with the verifier in order to retrieve the out-of-band secret or authentication request. This channel is considered to be out-of-band with respect to the primary communication channel (even if it terminates on the same device) provided the device does not leak information from one channel to the other without the authorization of the claimant.

The out-of-band device SHOULD be uniquely addressable by the verifier. Communication over the secondary channel SHALL be encrypted unless sent via the public switched telephone network (PSTN). For additional authenticator requirements specific to use of the PSTN for out-of-band authentication, see Sec. 5.1.3.3. Channels or addresses that do not prove possession of a specific device, such as voice-over-IP (VOIP) telephone numbers, SHALL NOT be used for out-of-band authentication.

Email SHALL NOT be used for out-of-band authentication because it also does not prove possession of a specific device and is typically accessed using only a memorized secret.

The out-of-band authenticator SHALL uniquely authenticate itself in one of the following ways when communicating with the verifier:

-

Establish an authenticated protected channel to the verifier using approved cryptography. The key used SHALL be stored in suitably secure storage available to the authenticator application (e.g., keychain storage, TPM, TEE, secure element).

-

Authenticate to a public mobile telephone network using a SIM card or equivalent that uniquely identifies the device. This method SHALL only be used if a secret is being sent from the verifier to the out-of-band device via the PSTN (SMS or voice).

If a secret is sent by the verifier to the out-of-band device, the device SHOULD NOT display the authentication secret while it is locked by the owner (i.e., SHOULD require the presentation and verification of a PIN, passcode, or biometric characteristic to view). However, authenticators SHOULD indicate the receipt of an authentication secret on a locked device.

If the out-of-band authenticator requests approval over the secondary communication channel — rather than by the presenting a secret that the claimant transfers to the primary communication channel — it SHALL accept transfer of the secret from the primary channel and send it to the verifier over the secondary channel to associate the approval with the authentication transaction. The claimant MAY perform the transfer manually or use a technology such as a barcode or QR code to effect the transfer.

Out-of-Band Verifiers

For additional verification requirements specific to the PSTN, see Sec. 5.1.3.3.

When the out-of-band authenticator is a secure application, such as on a smart phone, the verifier MAY send a push notification to that device. The verifier waits for the establishment of an authenticated protected channel with the out-of-band authenticator and verifies its identifying key. The verifier SHALL NOT store the identifying key itself, but SHALL use a verification method (e.g., an approved hash function or proof of possession of the identifying key) to uniquely identify the authenticator. Once authenticated, the verifier transmits the authentication secret to the authenticator.

Depending on the type of out-of-band authenticator, one of the following SHALL take place:

-

Transfer of secret from the secondary to the primary channel: The verifier MAY signal the device containing the subscriber’s authenticator to indicate readiness to authenticate. It SHALL then transmit a random secret to the out-of-band authenticator. The verifier SHALL then wait for the secret to be returned on the primary communication channel.

-

Transfer of secret from the primary to the secondary channel: The verifier SHALL display a random authentication secret to the claimant via the primary channel. It SHALL then wait for the secret to be returned on the secondary channel from the claimant’s out-of-band authenticator.

In all cases, the authentication SHALL be considered invalid if not completed within 10 minutes. In order to provide replay resistance as described in Sec. 5.2.8, verifiers SHALL accept a given authentication secret only once during the validity period.

The verifier SHALL generate random authentication secrets with at least 20 bits of entropy using an approved random bit generator [SP800-90Ar1]. If the authentication secret has less than 64 bits of entropy, the verifier SHALL implement a rate-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of failed authentication attempts that can be made on the subscriber account as described in Sec. 5.2.2.

Out-of-band verifiers SHALL consider all authentication operations to be single-factor unless the CSP has confirmed that the out-of-band authentication meets the requirements of Sec. 5.1.3.4. This requirement MAY be satisfied by issuance of the authenticator by the CSP or a trusted third party or by use of an authentication application known by the CSP to meet these requirements.

Out-of-band verifiers that send a push notification to a subscriber device SHOULD implement a reasonable limit on the rate or total number of push notifications that will be sent since the last successful authentication.

Authentication using the Public Switched Telephone Network

Use of the PSTN for out-of-band verification is restricted as described in this section and in Sec. 5.2.10. If out-of-band verification is to be made using the PSTN, the verifier SHALL verify that the pre-registered telephone number being used is associated with a specific physical device. Changing the pre-registered telephone number is considered to be the binding of a new authenticator and SHALL only occur as described in Sec. 6.1.2.

Use of the PSTN to deliver out-of-band authentication secrets is potentially not available to some subscribers in areas with limited telephone coverage (particularly in areas without mobile phone service). Accordingly, verifiers SHALL ensure that alternative authenticator types are available to all subscribers and SHOULD remind subscribers of this limitation of PSTN out-of-band authenticators prior to binding.

Verifiers SHOULD consider risk indicators such as device swap, SIM change, number porting, or other abnormal behavior before using the PSTN to deliver an out-of-band authentication secret.

NOTE: Consistent with the restriction of authenticators in Sec. 5.2.10, NIST may adjust the restricted status of the PSTN over time based on the evolution of the threat landscape and the technical operation of the PSTN.

Multi-Factor Out-of-Band Authenticators

Multi-factor out-of-band authenticators operate in a similar manner to single-factor out-of-band authenticators (see Sec. 5.1.3.1) except that they require the presentation and verification of an additional factor, either a memorized secret or a biometric characteristic, prior to allowing the claimant to complete the authentication transaction (i.e., prior to accessing the authentication secret, entering the authentication secret, or confirming the transaction as appropriate for the authentication flow being used). Each use of the authenticator SHALL require the presentation of the activation factor.

The use of an activation secret by the authenticator SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.11. A biometric activation factor SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.3, including limits on the number of consecutive authentication failures. Submission of the activation factor SHALL be a separate operation from unlocking of the host device (e.g., smartphone), although the same activation factor used to unlock the host device MAY be used in the authentication operation. The memorized secret or biometric sample used for activation — and any biometric data derived from the biometric sample such as a probe produced through signal processing — SHALL be zeroized immediately after the authentication operation.

Single-Factor OTP Device

A single-factor OTP device generates one-time passwords (OTPs). This category includes hardware devices and software-based OTP generators installed on devices such as mobile phones. These devices have an embedded secret that is used as the seed for generation of OTPs and does not require activation through a second factor. The OTP is displayed on the device and manually input for transmission to the verifier, thereby proving possession and control of the device. An OTP device may, for example, display 6 characters at a time. A single-factor OTP device is something you have.

Single-factor OTP devices are similar to look-up secret authenticators with the exception that the secrets are cryptographically and independently generated by the authenticator and verifier and compared by the verifier. The secret is computed based on a nonce that may be time-based or from a counter on the authenticator and verifier.

Single-Factor OTP Authenticators

Single-factor OTP authenticators contain two persistent values. The first is a symmetric key that persists for the device’s lifetime. The second is a nonce that is either changed each time the authenticator is used or is based on a real-time clock.

The secret key and its algorithm SHALL provide at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). The nonce SHALL be of sufficient length to ensure that it is unique for each operation of the device over its lifetime. If a subscriber needs to change the device used for a software-based OTP authenticator, they SHOULD bind the authenticator application on the new device to their subscriber account as described in Sec. 6.1.2.1 and invalidate the authenticator application that will no longer be used.

The authenticator output is obtained by using an approved block cipher or hash function to combine the key and nonce in a secure manner. The authenticator output MAY be truncated to as few as 6 decimal digits (approximately 20 bits of entropy).

If the nonce used to generate the authenticator output is based on a real-time clock, the nonce SHALL be changed at least once every 2 minutes.

Single-Factor OTP Verifiers

Single-factor OTP verifiers effectively duplicate the process of generating the OTP used by the authenticator. As such, the symmetric keys used by authenticators are also present in the verifier, and SHALL be strongly protected against unauthorized disclosure by the use of access controls that limit access to the keys to only those software components on the device requiring access.

When a single-factor OTP authenticator is being associated with a subscriber account, the verifier or associated CSP SHALL use approved cryptography to either generate and exchange or to obtain the secrets required to duplicate the authenticator output.

The verifier SHALL use approved encryption and an authenticated protected channel when collecting the OTP in order to provide resistance to eavesdropping and AitM attacks. In order to provide replay resistance as described in Sec. 5.2.8, verifiers SHALL accept a given OTP only once while it is valid. In the event a claimant’s authentication is denied due to duplicate use of an OTP, verifiers MAY warn the claimant in case an attacker has been able to authenticate in advance. Verifiers MAY also warn a subscriber in an existing session of the attempted duplicate use of an OTP.

Time-based OTPs [TOTP] SHALL have a defined lifetime that is determined by the expected clock drift — in either direction — of the authenticator over its lifetime, plus allowance for network delay and user entry of the OTP.

If the authenticator output has less than 64 bits of entropy, the verifier SHALL implement a rate-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of failed authentication attempts that can be made on the subscriber account as described in Sec. 5.2.2.

Multi-Factor OTP Devices

A multi-factor OTP device generates OTPs for use in authentication after activation through input of an activation factor. This includes hardware devices and software-based OTP generators installed on devices such as mobile phones. The second factor of authentication may be achieved through some kind of integral entry pad, an integral biometric (e.g., fingerprint) reader, or a direct computer interface (e.g., USB port). The OTP is displayed on the device and manually input for transmission to the verifier. For example, an OTP device may display 6 characters at a time, thereby proving possession and control of the device. The multi-factor OTP device is something you have, and it SHALL be activated by either something you know or something you are.

Multi-Factor OTP Authenticators

Multi-factor OTP authenticators operate in a similar manner to single-factor OTP authenticators (see Sec. 5.1.4.1), except that they require the presentation and verification of either a memorized secret or a biometric characteristic to obtain the OTP from the authenticator. Each use of the authenticator SHALL require the input of the activation factor.

In addition to activation information, multi-factor OTP authenticators contain two persistent values. The first is a symmetric key that persists for the device’s lifetime. The second is a nonce that is either changed each time the authenticator is used or is based on a real-time clock.

The secret key and its algorithm SHALL provide at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). The nonce SHALL be of sufficient length to ensure that it is unique for each operation of the device over its lifetime. If a subscriber needs to change the device used for a software-based OTP authenticator, they SHOULD bind the authenticator application on the new device to their subscriber account as described in Sec. 6.1.2.1 and invalidate the authenticator application that will no longer be used.

The authenticator output is obtained by using an approved block cipher or hash function to combine the key and nonce in a secure manner. The authenticator output MAY be truncated to as few as 6 decimal digits (approximately 20 bits of entropy).

If the nonce used to generate the authenticator output is based on a real-time clock, the nonce SHALL be changed at least once every 2 minutes.

The use of an activation secret by the authenticator SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.11. A biometric activation factor SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.3, including limits on the number of consecutive authentication failures. Submission of the activation factor SHALL be a separate operation from unlocking of the host device (e.g., smartphone), although the same activation factor used to unlock the host device MAY be used in the authentication operation. The unencrypted key and activation secret or biometric sample — and any biometric data derived from the biometric sample such as a probe produced through signal processing — SHALL be zeroized immediately after an OTP has been generated.

Multi-Factor OTP Verifiers

Multi-factor OTP verifiers effectively duplicate the process of generating the OTP used by the authenticator, but without the requirement that a second factor be provided. As such, the symmetric keys used by authenticators SHALL be strongly protected against unauthorized disclosure by the use of access controls that limit access to the keys to only those software components on the device requiring access.

When a multi-factor OTP authenticator is being associated with a subscriber account, the verifier or associated CSP SHALL use approved cryptography to either generate and exchange or to obtain the secrets required to duplicate the authenticator output. The verifier or CSP SHALL also establish, by issuance of the authentictor, that the authenticator is a multi-factor device. Otherwise, the verifier SHALL treat the authenticator as single-factor, in accordance with Sec. 5.1.4.

The verifier SHALL use approved encryption and an authenticated protected channel when collecting the OTP in order to provide resistance to eavesdropping and AitM attacks. In order to provide replay resistance as described in Sec. 5.2.8, verifiers SHALL accept a given OTP only once while it is valid. In the event a claimant’s authentication is denied due to duplicate use of an OTP, verifiers MAY warn the claimant in case an attacker has been able to authenticate in advance. Verifiers MAY also warn a subscriber in an existing session of the attempted duplicate use of an OTP.

Time-based OTPs [TOTP] SHALL have a defined lifetime that is determined by the expected clock drift — in either direction — of the authenticator over its lifetime, plus allowance for network delay and user entry of the OTP.

If the authenticator output or activation secret has less than 64 bits of entropy, the verifier SHALL implement a rate-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of failed authentication attempts that can be made on the subscriber account as described in Sec. 5.2.2.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software

A single-factor cryptographic software authenticator is a cryptographic key stored on disk or some other “soft” media. Authentication is accomplished by proving possession and control of the key. The authenticator output is highly dependent on the specific cryptographic protocol, but it is generally some type of signed message. The single-factor cryptographic software authenticator is something you have.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticators

Single-factor cryptographic software authenticators encapsulate one or more secret keys unique to the authenticator. The key SHALL be stored in suitably secure storage available to the authenticator application (e.g., keychain storage, TPM, or TEE if available). The key SHALL be strongly protected against unauthorized disclosure by the use of access controls that limit access to the key to only those software components on the device requiring access.

External cryptographic authenticators that do not meet the requirements of cryptographic hardware authenticators (e.g., that have a mechanism to allow private keys to be exported) are also considered to be cryptographic software authenticators. They SHALL meet the requirements for connected authenticators in Sec. 5.2.12.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Software Verifiers

The requirements for a single-factor cryptographic software verifier are identical to those for a single-factor cryptographic device verifier, described in Sec. 5.1.7.2.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Devices

A single-factor cryptographic device is a hardware device that performs cryptographic operations using protected cryptographic keys and provides the authenticator output via direct connection to the user endpoint. The device uses embedded symmetric or asymmetric cryptographic keys, and does not require activation through a second factor of authentication. Authentication is accomplished by proving possession of the device via the authentication protocol. The authenticator output is provided by direct connection to the user endpoint and is highly dependent on the specific cryptographic device and protocol, but it is typically some type of signed message. A single-factor cryptographic device is something you have.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Authenticators

Single-factor cryptographic device authenticators use tamper-resistant hardware to encapsulate one or more secret keys unique to the authenticator that SHALL NOT be exportable (i.e., cannot be removed from the device). The authenticator operates using a secret key to sign a challenge nonce presented through a direct interface between the authenticator and endpoint (e.g., a USB port or secured wireless connection) as specified in Sec. 5.2.12. Alternatively, the authenticator could be a suitably secure processor integrated with the user endpoint itself.

The secret key and its algorithm SHALL provide at least the minimum security length specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). The challenge nonce SHALL be at least 64 bits in length. Approved cryptography SHALL be used.

Cryptographic device authenticators differ from cryptographic software authenticators because of the greater protection afforded to the embedded authentication secrets by cryptographic devices. In order to be considered a cryptographic device, an authenticator SHALL either be a separate piece of hardware or an embedded processor or execution environment, e.g., secure element, trusted execution environment (TEE), trusted platform module (TPM). These hardware authenticators or embedded processors are separate from a host processor such as the CPU on a laptop or mobile device. A cryptographic device authenticator SHALL be designed so as to prohibit the export of the authentication secret to the host processor and SHALL NOT be capable of being reprogrammed by the host processor so as to allow the secret to be extracted. The authenticator is subject to applicable [FIPS140] requirements of the AAL at which the authenticator is being used.

Single-factor cryptographic device authenticators SHOULD require a physical input (e.g., the pressing of a button) in order to operate. This provides defense against unintended operation of the device, which might occur if the endpoint to which it is connected is compromised.

Single-Factor Cryptographic Device Verifiers

Single-factor cryptographic device verifiers generate a challenge nonce, send it to the corresponding authenticator, and use the authenticator output to verify possession of the device. The authenticator output is highly dependent on the specific cryptographic device and protocol, but it is generally some type of signed message.

The verifier has either symmetric or asymmetric cryptographic keys corresponding to each authenticator. While both types of keys SHALL be protected against modification, symmetric keys SHALL additionally be protected against unauthorized disclosure by the use of access controls that limit access to the key to only those software components on the device requiring access.

The challenge nonce SHALL be at least 64 bits in length, and SHALL either be unique over the authenticator’s lifetime or statistically unique (i.e., generated using an approved random bit generator [SP800-90Ar1]). The verification operation SHALL use approved cryptography.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software

A multi-factor cryptographic software authenticator is a cryptographic key stored on disk or some other “soft” media that requires activation through a second factor of authentication. Authentication is accomplished by proving possession and control of the key. The authenticator output is highly dependent on the specific cryptographic protocol, but it is generally some type of signed message. The multi-factor cryptographic software authenticator is something you have, and it SHALL be activated by either something you know or something you are.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software Authenticators

Multi-factor cryptographic software authenticators encapsulate one or more secret keys unique to the authenticator and accessible only through the presentation and verification of an activation factor, either a memorized secret or a biometric characteristic. The key SHOULD be stored in suitably secure storage available to the authenticator application (e.g., keychain storage, TPM, TEE). The key SHALL be strongly protected against unauthorized disclosure by the use of access controls that limit access to the key to only those software components on the device requiring access.

External cryptographic authenticators that do not meet the requirements of cryptographic hardware authenticators (e.g., that have a mechanism to allow private keys to be exported) are also considered to be cryptographic software authenticators. They SHALL meet the requirementss for connected authenticators in Sec. 5.2.12.

Each authentication operation using the authenticator SHALL require the input of the activation factor.

The use of an activation secret by the authenticator SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.11. A biometric activation factor SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.3, including limits on the number of consecutive authentication failures. Submission of the activation factor SHALL be a separate operation from unlocking of the host device (e.g., smartphone), although the same activation factor used to unlock the host device MAY be used in the authentication operation. The activation secret or biometric sample — and any biometric data derived from the biometric sample such as a probe produced through signal processing — SHALL be zeroized immediately after an authentication transaction has taken place.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Software Verifiers

The requirements for a multi-factor cryptographic software verifier are identical to those for a single-factor cryptographic device verifier, described in Sec. 5.1.7.2. Verification of the output from a multi-factor cryptographic software authenticator proves use of the activation factor.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Devices

A multi-factor cryptographic device is a hardware device that performs cryptographic operations using one or more protected cryptographic keys and requires activation through a second authentication factor. Authentication is accomplished by proving possession of the device and control of the key. The authenticator output is provided by direct connection to the user endpoint and is highly dependent on the specific cryptographic device and protocol, but it is typically some type of signed message. The multi-factor cryptographic device is something you have, and it SHALL be activated by either something you know or something you are.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device Authenticators

Multi-factor cryptographic device authenticators use tamper-resistant hardware to encapsulate one or more secret keys unique to the authenticator that SHALL NOT be exportable (i.e., cannot be removed from the device). The secret key SHALL be accessible only through the presentation and verification of an activation factor, either a biometric characteristic or an activation secret as described in Sec. 5.2.11. The authenticator operates by using a secret key that was unlocked by the activation factor to sign a challenge nonce presented through a direct interface between the authenticator and endpoint (e.g., a USB port or secured wireless connection) as specified in Sec. 5.2.12. Alternatively, the authenticator could be a suitably secure processor integrated with the user endpoint itself (e.g., a hardware TPM).

The secret key and its algorithm SHALL provide at least the minimum security length specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). The challenge nonce SHALL be at least 64 bits in length. Approved cryptography SHALL be used.

Cryptographic device authenticators differ from cryptographic software authenticators because of the greater protection afforded to the embedded authentication secrets by cryptographic devices. In order to be considered a cryptographic device, an authenticator SHALL either be a separate piece of hardware or an embedded processor or execution environment, e.g., secure element, trusted execution environment (TEE), trusted platform module (TPM). A cryptographic device authenticator SHALL be designed so as to prohibit the export of the authentication secret to the host processor and SHALL NOT be capable of being reprogrammed by the host processor so as to allow the secret to be extracted. The authenticator is subject to applicable [FIPS140] requirements of the AAL at which the authenticator is being used.

Each authentication operation using the authenticator SHOULD require the input of the activation factor. Input of the activation factor MAY be accomplished via either direct input on the device or via a hardware connection (e.g., USB, smartcard).

The use of an activation secret by the authenticator SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.11. A biometric activation factor SHALL meet the requirements of Sec. 5.2.3, including limits on the number of consecutive authentication failures. Submission of the activation factor SHALL be a separate operation from unlocking of the host device (e.g., smartphone), although the same activation factor used to unlock the host device MAY be used in the authentication operation. The activation secret or biometric sample — and any biometric data derived from the biometric sample such as a probe produced through signal processing — SHALL be zeroized immediately after an authentication transaction has taken place.

Multi-Factor Cryptographic Device Verifiers

The requirements for a multi-factor cryptographic device verifier are identical to those for a single-factor cryptographic device verifier, described in Sec. 5.1.7.2. Verification of the authenticator output from a multi-factor cryptographic device proves use of the activation factor.

General Authenticator Requirements

Physical Authenticators

CSPs SHALL provide subscriber instructions on how to appropriately protect the authenticator against theft or loss. The CSP SHALL provide a mechanism to invalidate the authenticator immediately upon notification from subscriber that loss or theft of the authenticator is suspected.

Rate Limiting (Throttling)

When required by the authenticator type descriptions in Sec. 5.1, the verifier SHALL implement controls to protect against online guessing attacks. Unless otherwise specified in the description of a given authenticator, the verifier SHALL limit consecutive failed authentication attempts on a single subscriber account to no more than 100.

Additional techniques MAY be used to reduce the likelihood that an attacker will lock the legitimate claimant out as a result of rate limiting. These include:

-

Requiring the claimant to complete a bot-detection and mitigation challenge before attempting authentication.

-

Requiring the claimant to wait following a failed attempt for a period of time that increases as the subscriber account approaches its maximum allowance for consecutive failed attempts (e.g., 30 seconds up to an hour).

-

Accepting only authentication requests that come from an allowlist of IP addresses from which the subscriber has been successfully authenticated before.

-

Leveraging other risk-based or adaptive authentication techniques to identify user behavior that falls within, or out of, typical norms. These might, for example, include use of IP address, geolocation, timing of request patterns, or browser metadata.

When the subscriber successfully authenticates, the verifier SHOULD disregard any previous failed attempts for that user from the same IP address.

Use of Biometrics

The use of biometrics (something you are) in authentication includes both measurement of physical characteristics (e.g., fingerprint, iris, facial characteristics) and behavioral characteristics (e.g., typing cadence). Both classes are considered biometric modalities, although different modalities may differ in the extent to which they establish authentication intent as described in Sec. 5.2.9.

For a variety of reasons, this document supports only limited use of biometrics for authentication. These reasons include:

- The biometric False Match Rate (FMR) does not provide confidence in the authentication of the subscriber by itself. In addition, FMR does not account for spoofing attacks.

- Biometric comparison is probabilistic, whereas the other authentication factors are deterministic.

- Biometric template protection schemes provide a method for revoking biometric credentials that is comparable to other authentication factors (e.g., PKI certificates and passwords). However, the availability of such solutions is limited, and standards for testing these methods are under development.

- Biometric characteristics do not constitute secrets. They can often be obtained online or, in the case of a facial image, by taking a picture of someone with or without their knowledge. Latent fingerprints can be lifted from objects someone touches, and iris patterns can be captured with high resolution images. While presentation attack detection (PAD) technologies can mitigate the risk of these types of attacks, additional trust in the sensor or biometric processing is required to ensure that PAD is operating in accordance with the needs of the CSP and the subscriber.

Therefore, the limited use of biometrics for authentication is supported with the following requirements and guidelines:

Biometrics SHALL be used only as part of multi-factor authentication with a physical authenticator (something you have).

The biometric system SHALL operate with a false-match rate (FMR) [ISO/IEC2382-37] of 1 in 10000 or better. This FMR SHALL be achieved under conditions of a conformant attack (i.e., zero-effort impostor attempt) as defined in [ISO/IEC30107-1].

The biometric system SHOULD implement presentation attack detection (PAD). Testing of the biometric system to be deployed SHOULD demonstrate at least 90% resistance to presentation attacks for each relevant attack type (i.e., species), where resistance is defined as the number of thwarted presentation attacks divided by the number of trial presentation attacks. Testing of presentation attack resistance SHALL be in accordance with Clause 12 of [ISO/IEC30107-3]. The PAD decision MAY be made either locally on the claimant’s device or by a central verifier.

The biometric system SHALL allow no more than 5 consecutive failed authentication attempts or 10 consecutive failed attempts if PAD, meeting the above requirements, is implemented. Once that limit has been reached, the biometric authenticator SHALL impose a delay of at least 30 seconds before each subsequent attempt, with an overall limit of no more than 50 consecutive failed authentication attempts (100 if PAD is implemented). Once the overall limit is reached, the biometric system SHALL disable biometric user authentication and offer another factor (e.g., a different biometric modality or an activation secret if it is not already a required factor) if such an alternative method is already available.

The verifier SHALL make a determination of sensor and endpoint performance, integrity, and authenticity. Acceptable methods for making this determination include, but are not limited to:

- Authentication of the sensor or endpoint

- Certification by an approved accreditation authority

- Runtime interrogation of signed metadata (e.g., attestation) as described in Sec. 5.2.4.

Biometric comparison can be performed locally on the claimant’s device or at a central verifier. Since the potential for attacks on a larger scale is greater at central verifiers, comparison SHOULD be performed locally.

If comparison is performed centrally:

- Use of the biometric as an authentication factor SHALL be limited to one or more specific devices that are identified using approved cryptography. Since the biometric has not yet unlocked the main authentication key, a separate key SHALL be used for identifying the device.

- Biometric revocation, referred to as biometric template protection in [ISO/IEC24745], SHALL be implemented.

- An authenticated protected channel between sensor (or an endpoint containing a sensor that resists sensor replacement) and verifier SHALL be established and the sensor or endpoint SHALL be authenticated prior to capturing the biometric sample from the claimant.

- All transmission of biometrics SHALL be over an authenticated protected channel.

Biometric samples collected in the authentication process MAY be used to train comparison algorithms or — with user consent — for other research purposes. Biometric samples and any biometric data derived from the biometric sample such as a probe produced through signal processing SHALL be zeroized immediately after any training or research data has been derived.

Biometric authentication technologies SHALL provide similar performance for subscribers of different demographic types (racial background, gender, ethnicity, etc.).

Attestation

An attestation is information conveyed to the verifier regarding a connected authenticator or the endpoint involved in an authentication operation. Information conveyed by attestation MAY include, but is not limited to:

- The provenance (e.g., manufacturer or supplier certification), health, and integrity of the authenticator and endpoint

- Security features of the authenticator

- Security and performance characteristics of biometric sensors

- Sensor modality

If this attestation is signed, it SHALL be signed using a digital signature that provides at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication).

Attestation information MAY be used as part of a verifier’s risk-based authentication decision.

Phishing (Verifier Impersonation) Resistance

Phishing attacks, previously referred to in SP 800-63B as “verifier impersonation,” are attempts by fraudulent verifiers and RPs to fool an unwary claimant into presenting an authenticator to an impostor. In some prior versions of SP 800-63, protocols resistant to phishing attacks were also referred to as “strongly MitM resistant.”

The term phishing is widely used to describe a variety of similar attacks. For the purposes of this document, phishing resistance is the ability of the authentication protocol to detect and prevent disclosure of authentication secrets and valid authenticator outputs to an impostor relying party without reliance on the vigilance of the subscriber. The means by which the subscriber was directed to the impostor relying party are not relevant. For example, regardless of whether the subscriber was directed there via search engine optimization or prompted by email, it is considered to be a phishing attack.

Approved cryptographic algorithms SHALL be used to establish phishing resistance where it is required. Keys used for this purpose SHALL provide at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication).

Authenticators that involve the manual entry of an authenticator output, such as out-of-band and OTP authenticators, SHALL NOT be considered phishing resistant because the manual entry does not bind the authenticator output to the specific session being authenticated. In an AitM attack, an impostor verifier could replay the OTP authenticator output to the verifier and successfully authenticate.

While an individual authenticator may be phishing resistant, phishing resistance for a given subscriber account is only achieved when all methods of authentication are phishing resistant.

Two methods of phishing resistance are recognized: channel binding and verifier name binding. Channel binding is considered more secure than verifier name binding because it is not vulnerable to mis-issuance or misappropriation of relying party certificates, but either method satisfies the requirements for phishing resistance.

Channel Binding

An authentication protocol with channel binding SHALL establish an authenticated protected channel with the verifier. It SHALL then strongly and irreversibly bind a channel identifier that was negotiated in establishing the authenticated protected channel to the authenticator output (e.g., by signing the two values together using a private key controlled by the claimant for which the public key is known to the verifier). The verifier SHALL validate the signature or other information used to prove phishing resistance. This prevents an impostor verifier, even one that has obtained a certificate representing the actual verifier, from successfully relaying that authentication on a different authenticated protected channel.

An example of a phishing resistant authentication protocol that uses channel binding is client-authenticated TLS, because the client signs the authenticator output along with earlier messages from the protocol that are unique to the particular TLS connection being negotiated.

Verifier Name Binding

An authentication protocol with authenticator name binding SHALL establish an authenticated protected channel with the verifier. It SHALL then generate an authenticator output that is cryptographically bound to a verifier identifier that is authenticated as part of the protocol. In the case of domain name system (DNS) identifiers, the verifier identifier SHALL be either the authenticated hostname of the verifier or a parent domain that is at least one level below the public suffix [PSL] associated with that hostname. The binding MAY be established by choosing an associated authenticator secret, by deriving an authenticator secret using the verifier identifier, by cryptographically signing the authenticator output with the verifier identifier, or similar cryptographically secure means.

Verifier-CSP Communications

In situations where the verifier and CSP are separate entities (as shown by the dotted line in [SP800-63] Figure 1), communications between the verifier and CSP SHALL occur through a mutually authenticated secure channel (such as a client-authenticated TLS connection) using approved cryptography.

Verifier Compromise Resistance

Use of some types of authenticators requires that the verifier store a copy of the authenticator secret. For example, an OTP authenticator (described in Sec. 5.1.4) requires that the verifier independently generate the authenticator output for comparison against the value sent by the claimant. Because of the potential for the verifier to be compromised and stored secrets stolen, authentication protocols that do not require the verifier to persistently store secrets that could be used for authentication are considered stronger, and are described herein as being verifier compromise resistant. Note that such verifiers are not resistant to all attacks. A verifier could be compromised in a different way, such as being manipulated into always accepting a particular authenticator output.

Verifier compromise resistance can be achieved in different ways, for example:

-

Use a cryptographic authenticator that requires the verifier store a public key corresponding to a private key held by the authenticator.

-

Store the expected authenticator output in hashed form. This method can be used with some look-up secret authenticators (described in Sec. 5.1.2), for example.

To be considered verifier compromise resistant, public keys stored by the verifier SHALL be associated with the use of approved cryptographic algorithms and SHALL provide at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication).

Other verifier compromise resistant secrets SHALL use approved hash algorithms and the underlying secrets SHALL have at least the minimum security strength specified in the latest revision of [SP800-131A] (112 bits as of the date of this publication). Secrets (e.g., memorized secrets) having lower complexity SHALL NOT be considered verifier compromise resistant when hashed because of the potential to defeat the hashing process through dictionary lookup or exhaustive search.

Replay Resistance

An authentication process resists replay attacks if it is impractical to achieve a successful authentication by recording and replaying a previous authentication message. Replay resistance is in addition to the replay-resistant nature of authenticated protected channel protocols, since the output could be stolen prior to entry into the protected channel. Protocols that use nonces or challenges to prove the “freshness” of the transaction are resistant to replay attacks since the verifier will easily detect when old protocol messages are replayed since they will not contain the appropriate nonces or timeliness data.

Examples of replay-resistant authenticators are OTP devices, cryptographic authenticators, and look-up secrets.

In contrast, memorized secrets are not considered replay resistant because the authenticator output — the secret itself — is provided for each authentication.

Authentication Intent

An authentication process demonstrates intent if it requires the subject to explicitly respond to each authentication or reauthentication request. The goal of authentication intent is to make it more difficult for authenticators (e.g., multi-factor cryptographic devices) to be used without the subject’s knowledge, such as by malware on the endpoint. Authentication intent SHALL be established by the authenticator itself, although multi-factor cryptographic devices MAY establish intent by reentry of the activation factor for the authenticator.

Authentication intent MAY be established in a number of ways. Authentication processes that require the subject’s intervention establish intent (e.g., a claimant entering an authenticator output from an OTP device). Cryptographic devices that require user action for each authentication or reauthentication operation also establish intent (e.g., pushing a button or reinsertion).

Depending on the modality, presentation of a biometric characteristic may or may not establish authentication intent. Behavioral biometrics similarly may or may not establish authentication intent because they do not always require a specific action on the claimant’s part.

Restricted Authenticators

As threats evolve, authenticators’ capability to resist attacks typically degrades. Conversely, some authenticators’ performance may improve, for example, when changes to their underlying standards increases their ability to resist particular attacks.

To account for these changes in authenticator performance, NIST places additional restrictions on authenticator types or specific classes or instantiations of an authenticator type.

The use of a restricted authenticator requires that the implementing organization assess, understand, and accept the risks associated with that authenticator and acknowledge that risk will likely increase over time. It is the responsibility of the organization to determine the level of acceptable risk for their systems and associated data and to define any methods for mitigating excessive risks. If at any time the organization determines that the risk to any party is unacceptable, then that authenticator SHALL NOT be used.

Further, the risk of an authentication error is typically borne by multiple parties, including the implementing organization, organizations that rely on the authentication decision, and the subscriber. Because the subscriber may be exposed to additional risk when an organization accepts a restricted authenticator and that the subscriber may have a limited understanding of and ability to control that risk, the CSP SHALL:

-

Offer subscribers at least one alternate authenticator that is not restricted and can be used to authenticate at the required AAL.

-

Provide meaningful notice to subscribers regarding the security risks of the restricted authenticator and availability of alternatives that are not restricted.

-

Address any additional risk to subscribers in its risk assessment.

-

Develop a migration plan for the possibility that the restricted authenticator is no longer acceptable at some point in the future and include this migration plan in its digital identity acceptance statement.

Activation Secrets

Memorized secrets that are used as an activation factor for a multi-factor authenticator are referred to as activation secrets. An activation secret is used to decrypt a stored secret key used for authentication or is compared against a locally held stored verifier to provide access to the authentication key. In either of these cases, the activation secret SHALL remain within the authenticator and its associated user endpoint.

Authenticators making use of activation secrets SHALL require the secrets to be at least 6 characters in length. Activation secrets MAY be entirely numeric (i.e., a PIN). If alphanumeric (rather than only numeric) values are permitted, all printing ASCII [RFC20] characters as well as the space character SHOULD be accepted. Unicode [ISO/ISC 10646] characters SHOULD be accepted as well in alphanumeric secrets. The authenticator SHALL contain a blocklist (either specified by specific values or by an algorithm) of at least 10 commonly used activation values and SHALL prevent their use as activation secrets.

The authenticator or verifier SHALL implement a retry-limiting mechanism that effectively limits the number of consecutive failed activation attempts using the authenticator to ten (10). If the entry of an incorrect activation secret causes the authenticator to generate an invalid output that is sent to the central verifier, rate limiting MAY be implemented by the verifier. In all other cases, rate limiting SHALL be implemented in the authenticator. Once the limit of 10 attempts is reached, the authenticator SHALL be disabled and a different authenticator SHALL be required for authentication.

If the authenticator verifies the activation secret locally (rather than using it for decryption of a key), verification SHALL be performed within a hardware-based authenticator or in a secure element (e.g., TEE, TPM) that releases the authentication secret only upon presentation of the correct activation secret. In other circumstances (i.e., software-based multi-factor authenticators), the authenticator SHALL use the memorized secret as a key to decrypt its stored authentication secret. Approved cryptography SHALL be used.

Connected Authenticators

Cryptographic authenticators require a direct connection between the authenticator and the endpoint being authenticated. This connection MAY be wired (e.g., USB or direct connection with a smartcard) or wireless (e.g., NFC, Bluetooth). While in most cases wired connections can be presumed to be secure from eavesdropping and adversary-in-the-middle attacks, additional precautions are required for authenticators that are connected via wireless technologies.

Wired authenticator connections include both authenticators that are embedded in endpoints (e.g., in a TPM) and those that are connected via an external interface, such as USB. Claimants SHOULD be advised to use trusted hardware (cables, etc.) for external connections for additional assurance that they have not been compromised.

Wireless authenticator connections are potentially vulnerable to threats including eavesdropping, injection, and relay attacks. The potential for such attacks depends on the effective range of the wireless technology being used.

Wireless technologies having an effective range of 1 meter or more (e.g., Bluetooth LE) SHALL use an authenticated encrypted connection between the authenticator and endpoint. A pairing process SHALL be used to establish a key for encrypted communication between the authenticator and endpoint. A temporary wired connection between the devices MAY also be used to establish the key in lieu of the pairing process. The pairing process SHALL be authenticated through the use of a pairing code. The pairing code SHALL be associated with either the authenticator or endpoint and SHALL have at least 20 bits or 6 decimal digits of entropy. The pairing code MAY be printed on the associated device and SHALL be conveyed between the devices by manual entry or by using a QR code or similar representation that is optically communicated. An example of this is the pairing code used with the virtual contact interface specified in [SP800-73]. The entire authentication transaction SHALL be encrypted using a key established by the pairing process.

When a wireless technology with an effective range of less than 1 meter is in use (e.g., NFC), the activation secret, if any, transmitted from the endpoint to authenticator SHALL be encrypted using a key established through a pairing process between the devices or through a temporary wired connection. An authenticated connection using a pairing code meeting the above requirements SHOULD be used. If the authenticator is configured to require authenticated pairing, pairing code SHALL be used.

Note: Encryption of only the activation secret, and not the entire authentication transaction, may expose sensitive information such as the identity of the relying party, although this would require the attacker to be very close to the subscriber. Special care should be taken with authenticators containing personally identifiable information that do not require authenticated pairing to protect that information against “skimming” and eavesdropping attacks.

The key established as a result of the pairing process MAY be either temporary (valid for a limited number of transactions or time) or persistent. A mechanism for endpoints to remove persistent keys SHALL be provided.

Where cryptographic operations are required, approved cryptography SHALL be used. All communication of authentication data between authenticators and endpoints SHALL occur directly between those devices or through an authenticated protected channel between the authenticator and endpoint.