Introduction#

This document provides an example of how to conduct genomic data threat modeling for privacy on processing environments to help identify potential threats, prioritize them, and develop potential interventions. The term threat modeling is used here for privacy to describe a process consistent with the cybersecurity threat modeling document [Ref7] as both cybersecurity and privacy issues can arise in genomic data processing. The environments represent a baseline implementation with devices, processes, and tools commonly used by government, academia, and industry for processing genomic data in clinical and research contexts.

Audience and Purpose#

This paper is intended for organizations that process genomic datasets in clinical or research contexts. Genomic data processing includes sequencing genomic material as well as storing, analyzing, transferring, and appropriate destruction of genomic data. These organizations can apply the threat modeling process to develop dataflow diagrams (DFDs), identify threats, and understand interventions. Threat modeling can be used to:

Guide system development and assess the threat reduction value of proposed threat interventions.

Assess proposed changes to architecture or functionality for impacts on system threat and risk posture.

Evaluate and respond to threat environment changes, such as threat intelligence or incident.

Develop a Privacy Framework Organizational Profile that tailors the Genomic Data Profile [Ref5] to identify and prioritize threat-informed capabilities.

Incorporate threats into the NIST PRAM [Ref1] by mapping the validated threats into the standard Worksheet 3 (Prioritizing Risk) based on the associated data actions, assigning relevant Problematic Data Actions and Problems for Individuals, and using the attack feasibility and difficulty combination values (converted to a 10-point scale) as surrogates for likelihood.

Scope and Use Cases#

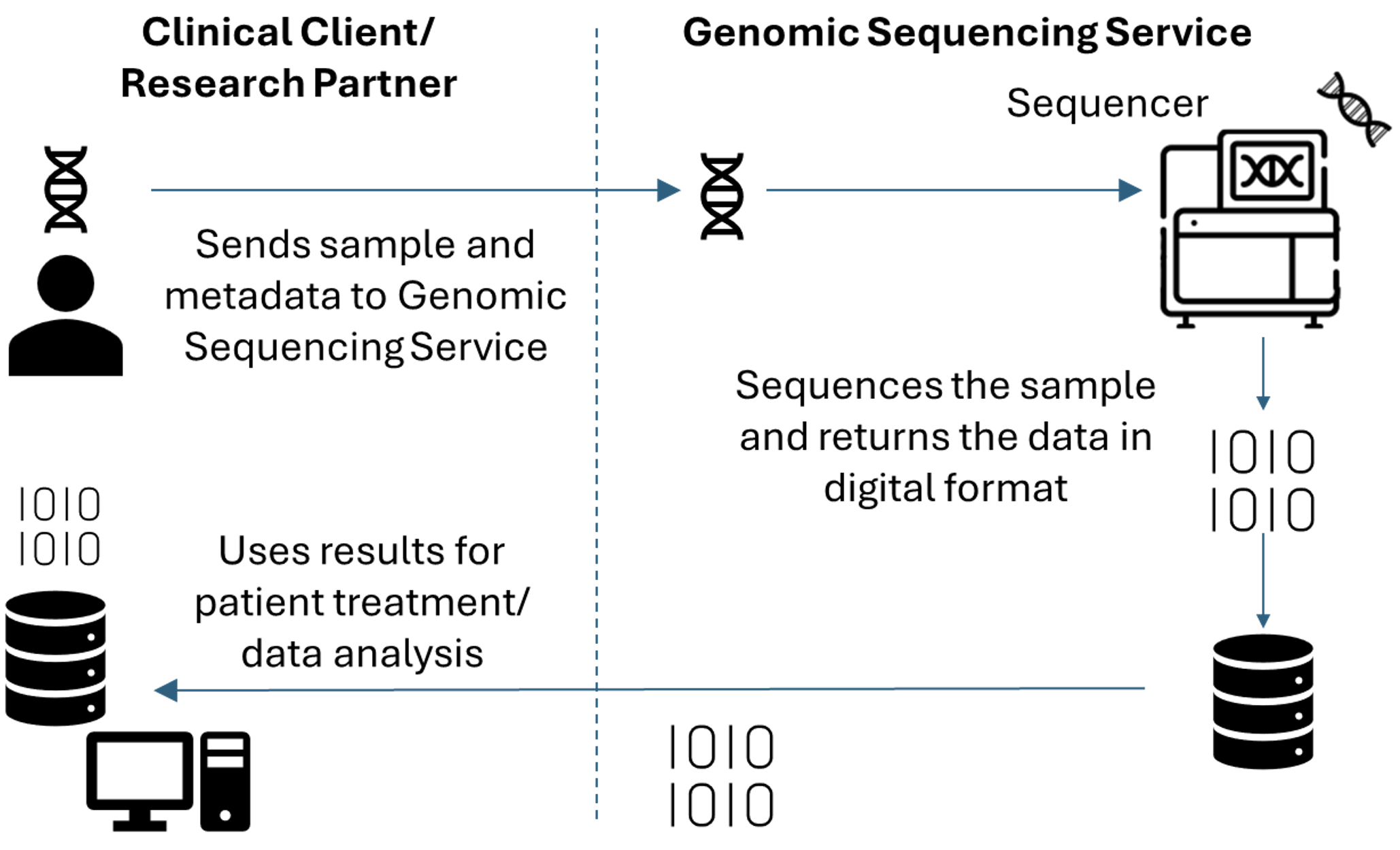

This threat modeling example addresses common elements of a genomics workflow including sending physical samples to a sequencing service provider, sequencing of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and receiving the resulting data from the service provider. The biotechnology sector relies on elements of this workflow for many of its products and services. This workflow includes several types of entities, including commonly a Clinical Client/Research Partner and a Genomic Sequencing Service. [1] While there are distinct differences between clinical and research contexts, they share a core workflow. In the example workflow, a client/partner sends a specimen [2] to the genomic sequencing service to process the sample and return digital data in the form of a genomic sequence or analytical test results. The genomic sequence serves as an input to the client/partner’s bioinformatics data analysis pipelines and can be used to support patient care by the Clinical Client. For this work, the NCCoE sent a DNA reference material (Clinical Client/Research Partner) to a genomic center (Genomic Sequencing Service) to sequence the sample then transfer the data back using a widely adopted protocol to the NCCoE for secondary analysis. Figure 1 illustrates this genomic sequencing workflow but does not depict the subsequent handling of data after its initial use. Organizations may either retain or dispose of data, based on its intended purpose and the organization’s data retention practices and according to patient or research subject consent.

Figure 1 illustrates this genomic sequencing workflow.

Figure 1. Genomic Sequencing Workflow#

Throughout this document, we use a limited core example to illustrate the described methods. This core example is a generalized version of the analyzed processes that are common to both the clinical and the research use cases. Artifacts related to the complete example that are not included in the body of this paper can be found in the designated appendices. The complete example includes more comprehensive analysis of both the clinical and research cases.

Genomic Data Characteristics#

The nature of human genomic data poses challenges for privacy. As a biometric it is immutable (unlike, for example, a password or a phone number). When genomic data is leaked or moves beyond a sphere of control, the affected data subjects cannot respond by simply changing their genomes. Moreover, that durability can motivate the prolonged retention of genomic data over time, rendering it more vulnerable to eventual disclosure or misuse.

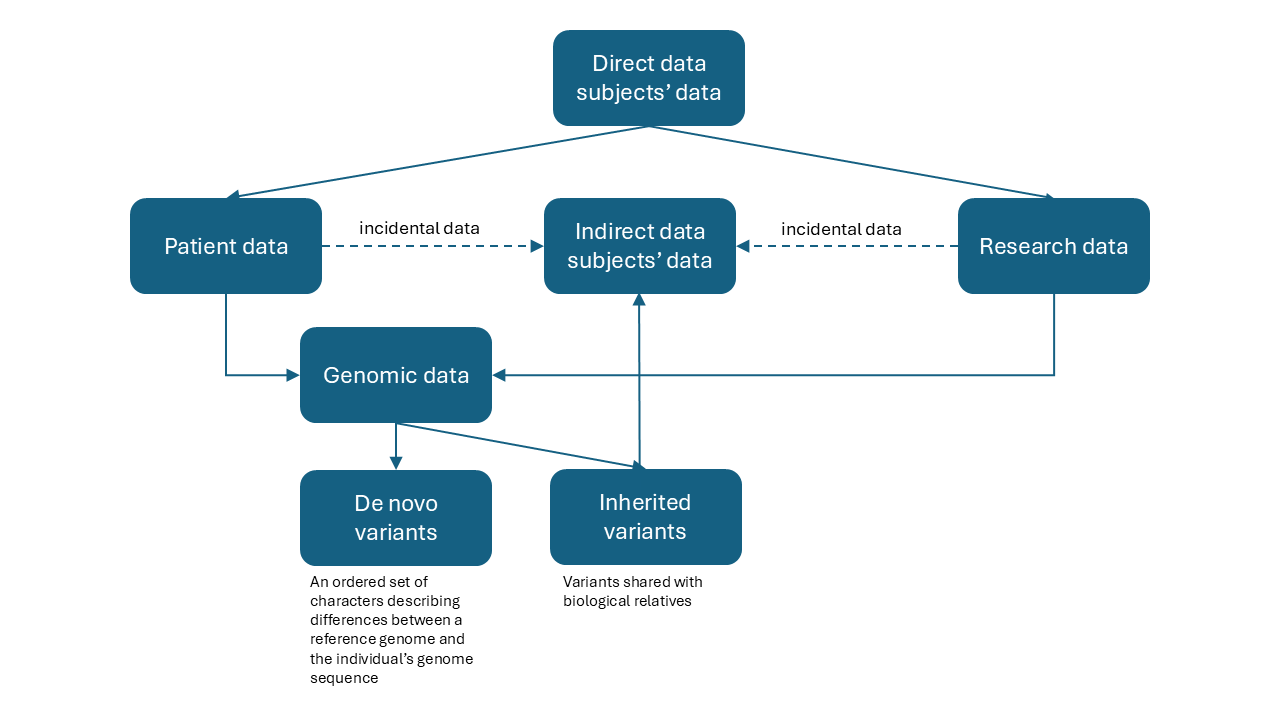

Equally problematic is the extent of the information contained in a person’s genome. While the interpretability of genomic data varies, the risk to privacy extends beyond identification. Genomic data can reveal a variety of health-related conditions or susceptibility to conditions. It can also reveal family connections and in doing so imply the potential health status or predisposition of others beyond the original data subject. This is in addition to the incidental data (e.g., contact information) that these others may share with the original data subject. It is therefore useful to distinguish between direct (i.e., sample provider) and indirect data subjects (i.e., biological relatives). Figure 2 illustrates these relationships for both the clinical and research use cases, where the direct data subject is a patient and/or research subject.

Figure 2. Genomic Data Relationships#

Privacy Landscape#

NIST SP 800-188 [Ref8] that focuses on techniques to de-identify government datasets includes a glossary definition of privacy as, “Freedom from intrusion into the private life or affairs of an individual when that intrusion results from undue or illegal gathering and use of data about that individual,” though universal agreement on a definition is still forming. However, the privacy literature includes different types of privacy associated with the contexts in which privacy problems may arise. While individual classifications may differ, they tend to resemble one another. Considering those classes specified by International Association of Privacy Professionals, of relevance to genomics are physical or bodily privacy [3] (i.e., privacy problems that deal with the human body or bodily functions) and information [4] or data privacy [5] (i.e., privacy problems that arise based on how data is processed). In the context of genomics, physical or bodily privacy applies to the acquisition of biospecimens from individuals while information or data privacy applies to symbolic representations of those specimens and any information derived from them, as well as accompanying metadata or identifiers (e.g., medical record numbers), demographics (e.g., age, gender), and diagnostic codes.

Those individuals to whom information or data pertain are often referred to as “data subjects” to emphasize the connection between the two. Information or data privacy is often confused with data security owing to their common interest in confidentiality (protecting data from unauthorized access or disclosure). However, data confidentiality is only one facet of data privacy out of many, including aspects of control over data and constraints on the collection and use of data. (While privacy is dependent on security, that dependency is not explicitly covered here given the cybersecurity threat modeling described in NIST CSWP 35 [Ref7].) This broader landscape of privacy is recognized in systems-level applications including the NIST Privacy Engineering Objectives (PEOs) of predictability, manageability, and disassociability [Ref9] as well as in higher level descriptions such as in the Fair Information Practice Principles (variations of which form a widely used basis for data privacy, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) privacy guidelines [Ref10]).

Risk Modeling Overview#

Risk modeling applies to both privacy and cybersecurity. Cybersecurity risk modeling centers on protecting organizations, whereas privacy focuses on individuals and groups. While realized privacy risks can include negative effects on an organization, their primary impacts are on people. Privacy risks are highly contextual because individuals and groups vary in their perceptions, preferences, and understanding of privacy and the complex systems that influence them.

Risk modeling identifies a range of potential risks for evaluation. A risk arises when a threat exploits a vulnerability, leading to an adverse outcome. However, not every threat will exploit every potential vulnerability. While each element of risk modeling—threats, vulnerabilities, and consequences—can be analyzed individually; threat modeling focuses specifically on understanding the threat component. To maximize the applicability of this paper’s workflow (sequencing genomic material), the process focuses on threats instead of risks. In this paper, a genomic data threat related to privacy is any circumstance or event with the potential to compromise the predictability, manageability, and/or disassociability [6] of systems involving data associated with individuals (adapted from the NIST Privacy Framework [Ref4] and NIST IR 8062 [Ref9]). Note that genomic data privacy threats are distinct from the adverse consequences that could result from such compromises and can arise without external factors.

Threat Modeling Overview#

Threat modeling can support a broad stakeholder base who can then integrate the results into their larger and more specific risk modeling and management efforts.

The NCCoE team used the Four Question Framework, illustrated in the Appendix Figure 1, to structure the threat modeling process by answering:

“What are we working on?”

“What could go wrong?”

“What are we going to do about it?”

“Did we do a good job?””

In each of the four questions, “we” refers to the team performing the threat modeling. Though the questions are listed in sequential order, the process is iterative. Each question is addressed through specific techniques outlined in this paper. Answers to one question may be used to modify previous answers or highlight the incompleteness of an answer to a previous question. Threat modeling results improve through each iteration and should be conducted throughout the system’s life cycle and whenever changes in the environment may impact threats. NIST CSWP 35 [Ref7] demonstrates how the Four-Question Framework can be applied to cybersecurity threat modeling of a genomic data sequencing workflow.

Appendix C provides details for each tool used in this exercise with important details provided in this subsection. Threat modeling tools used in this exercise include the following:

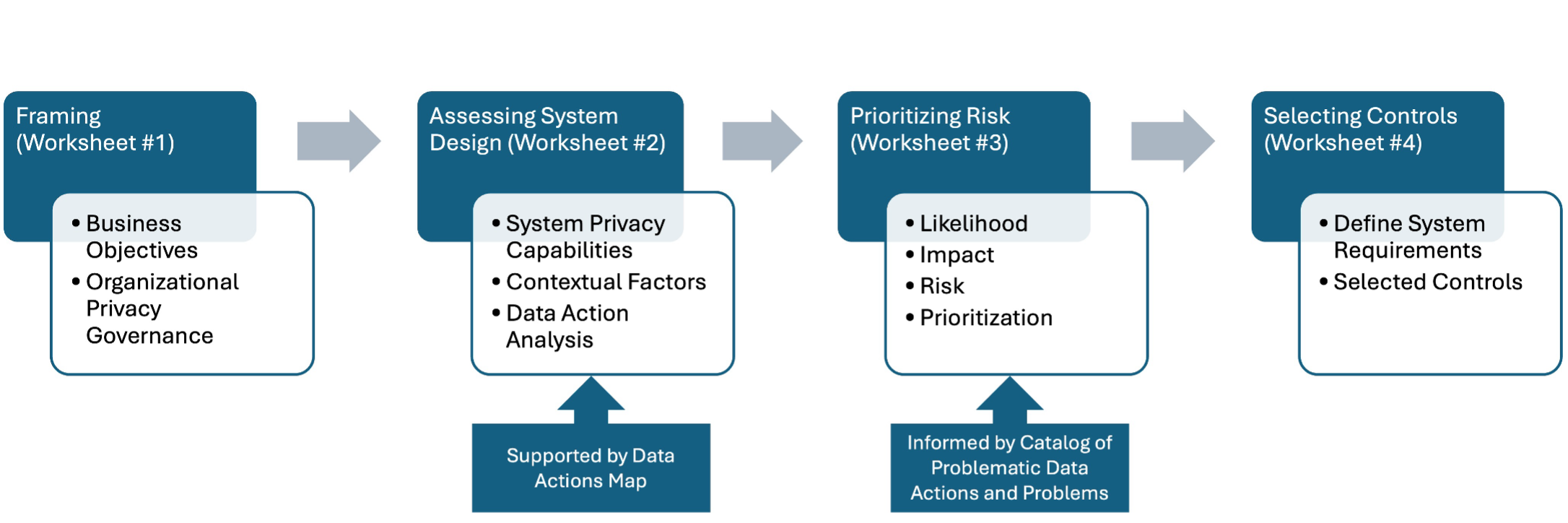

NIST PRAM [Ref1]: NIST’s Privacy Engineering Program produced the Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology for identifying system privacy risks. Figure 3 shows the four PRAM worksheets: 1) Framing Business Objectives & Organizational Privacy Governance, 2) Assessing System Design (includes a separate Supporting Data Map), 3) Prioritizing Risk, and 4) Selecting Controls. The PRAM also leverages a non-exhaustive privacy risk model consisting of “Problematic Data Actions” that may result in adverse effects for individuals listed in “Problems for Individuals.”

Figure 3. Overview of the NIST PRAM#

LINDDUN: A threat modeling tool for privacy inspired by the cybersecurity threat modeling tool STRIDE [Ref5],the name is an acronym comprising seven different threat types: Linking, Identifying, Non-repudiation, Detecting, Data disclosure, Unawareness and Unintervenability, and Non-compliance. This technique relies on Dataflow Diagrams, which are useful for data privacy analysis and understanding the data life cycle.

PANOPTIC: A privacy analog to MITRE ATT&CK, the Pattern and Action Nomenclature of Privacy Threats in Context, was created based on real-world privacy attacks drawn from multiple sources. PANOPTIC has two closely related taxonomies of Contextual Domains and Privacy Activities that are enumerated in Table 23 and 24 of Appendix C.