Introduction

This document describes the efforts of the Public Safety Use Case & Data Reference project. This project’s main focus was to explore how to provide meaningful cyber security guidance for public safety mobile applications. As with most projects, its scope and goals changed over time. The project began as an effort to better classify the information moving through public safety-centered mobile apps from a cybersecurity perspective. As the project grew we determined this was a subset of a more general concept: the relationship between information and public safety use cases. In tandem with this, the goals shifted from providing a static reference to public safety to exploring more interactive strategies to engage with the subject matter. The remainder of this section describes how we defined the project’s scope and what our proposed solutions were.

Problem Statement

How can PSCR provide guidance on the secure use and design of mobile apps for public safety?

PSCR is uniquely situated to provide this feedback to public safety. However, because public safety has not yet fully embraced mobile apps into their missions, providing this guidance is difficult because it is unclear how mobile apps will be used, what data they will require, and what requirements that data will have.

The requirements of public safety are diverse and multifaceted. As public safety incorporates more mobile technology into their mission strategies, they will be faced with the difficult proposition of evaluating those mobile solutions from the perspectives of usability, interoperability, and cybersecurity. This includes, but is not limited to, the use of more and more mobile applications (apps). The catch-22 is that the mobile application market for public safety is bourgeoning, meaning that many of the future must-have public safety apps have yet to be developed. Furthermore, many non-public safety mobile apps have been/will be adopted for use in public safety missions.

How then can PSCR provide guidance on the use and security of software that does not yet exist?

Proposed Solution

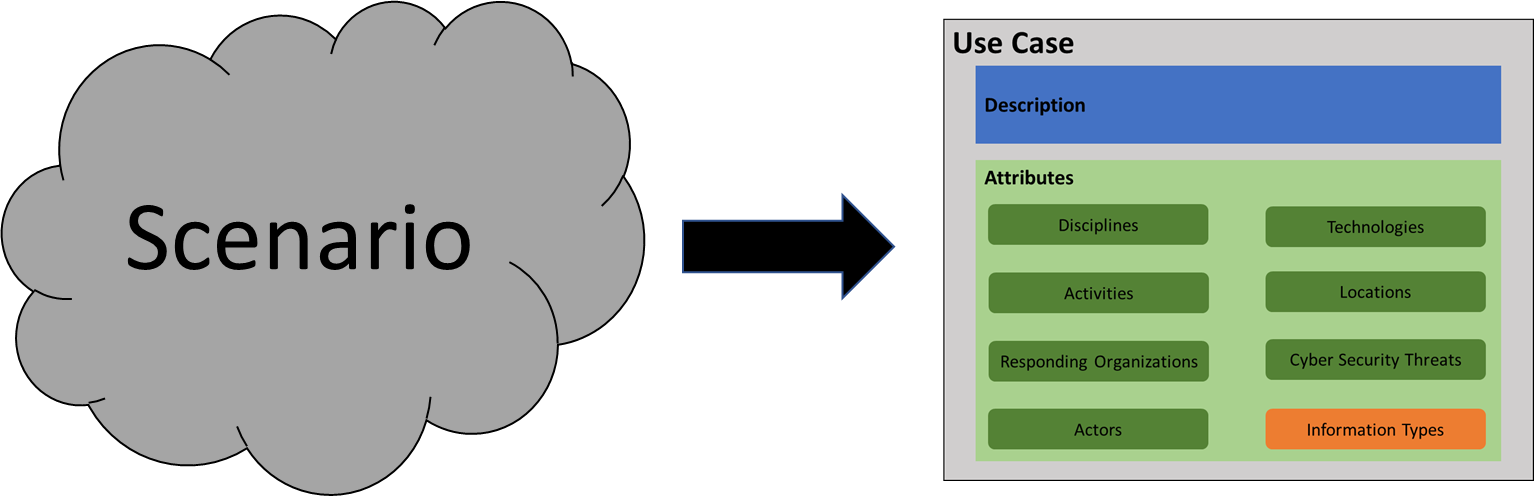

The answer lies in the intuition that apps are merely tools meant to aid in accomplishing public safety scenarios. This of course means their functionality is tightly connected to the scenarios that public safety encounters. As such, we can use these scenarios as proxies for the apps that would be used to facilitate them. Moving the target from an app to a scenario shifts the burden from characterizing something unknown (an app) to observing actual public safety activities, rules, regulations, and best practices.

Relying on real world scenarios satisfied one of our major concerns: grounding our guidance in authentic public safety activities prevents us from simply guessing about what scenarios actually entail.

However, this still begs the question of how to bridge the gap between the description of a public safety scenario (a traffic stop, car accident, building fire, etc.) and meaningful cybersecurity guidance. The first step in the NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF) involves categorizing a system and the information processed, stored, and transmitted by that system based on an impact analysis in terms of risk. We propose using the scenario as a proxy for the system at the center of the RMF. The impact analysis of information related to the scenario can therefore set us on the path toward meaningful cybersecurity guidance and recommendation.

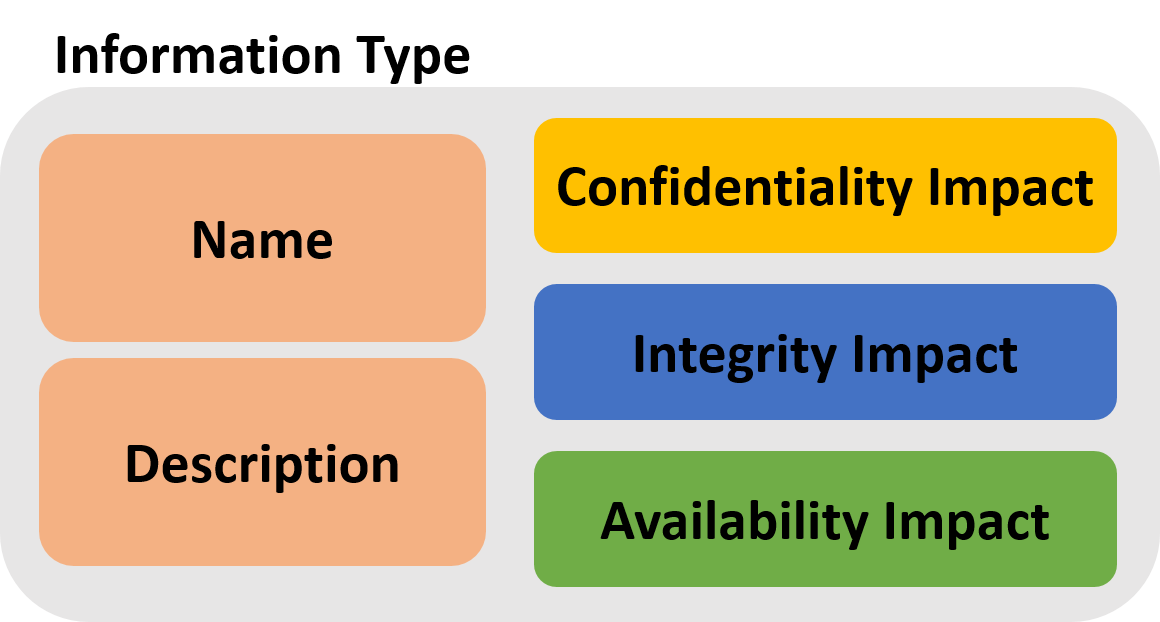

NIST FIPS 199 defines an information type as a specific category of information (e.g., privacy, medical, proprietary, financial, investigative, contractor sensitive, security management), defined by an organization, or in some instances, by a specific law, Executive Order, directive, policy, or regulation. The relationship of an information type to the three core cybersecurity objectives confidentiality, integrity, and availability characterizes the impact this information type can have on risk.

Therefore, we can achieve our goal of providing cyber security guidance for public safety mobile apps by accurately describing public safety scenarios, the information types that are inherent to them, and describing the impact these information types have on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability. We call this interplay between factors a use case.

Document structure/remainder of document

The remainder of this document describes in more detail the structure and usage of use case. Section 2 describes the 3 core audiences we identified as part of our research. Section 3 details the formalization we used to describe a public safety use case. Section 4 describes the process we used to express scenarios found from various sources in terms of our model. Section 5 describes a prototype web application we designed as a proof-of-concept capture and delivery mechanism for our use case formalization. Section 6 contains possible paths forward with this research, including information gathered from stakeholders. Finally, Appendix A contains a fledgling dataset of use cases structured in the formalization described in Section 3.

Intended Audience Stakeholders

The problem statement detailed in Section 1.1 identifies PSCR’s unique role to provide cybersecurity guidance to public safety concerning the use of mobile apps. To ensure we are effectively formulating and communicating this guidance, it is imperative to understand who we expect this guidance to be for, and how they will use it. During the formulation of this project, we identified three core Audience Stakeholders: public safety users, public safety researchers, and mobile app developers/mobile application vetting tools. The remainder of this section explores each of these stakeholder groups.

Public Safety Users

Public safety users are the primary stakeholder for this work. Specifically, those within public safety who will choose which apps should be allowed operate on devices used by first responders. NIST SP 800-163 describes a mobile app vetting process through which an organization can approve or reject the use of a mobile app. A key step in this process is the assessment of the application against pertinent cybersecurity requirements. In the case of public safety, these organization requirements can come from many potential sources:

-

Policies established by the organizations themselves (i.e. the state police, county fire departments, etc.)

-

Policies managed through inter-organization agreements, for example those made between neighboring counties

-

Policies required by service and data providers, for example those required by Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS)

-

Best practices for cybersecurity as advocated by Federal regulation or non-profit organizations.

The guidance provided by PSCR should enable public safety to choose apps while weighing the risk involved with deploying and using them. This means being able to evaluate apps for their potential adverse impacts to organizational operations (including mission, functions, image, or reputation), organizational assets, individuals, other organizations, and the Nation. This requires evaluating mobile apps, the information they utilize, and the functions they provide in terms of these impacts.

PSCR Researchers

When this project was first conceived, we identified an interesting overlap between how we were answering the concerns of our primary audience and that of a related audience: researchers here at PSCR. Namely, we found ourselves asking the same questions as other research efforts here in PSCR. The central question being: “what are the use cases surrounding the technology that is the focus of my research?” From this question, tangential questions naturally follow:

-

Who are the actors involved and how do I define them?

-

What resources are they using and what do I need to know about those resources?

-

What requirements are involved in terms of usability, criticality, and cybersecurity?

-

How does my research domain mesh with other areas of interest?

While the answer to each of these questions differs on what PSCR portfolio your research falls in, we identified a potential area of overlapping benefit. If there were a common repository of use cases for PSCR researchers to leverage, we could help streamline, augment, and unify research efforts within the division.

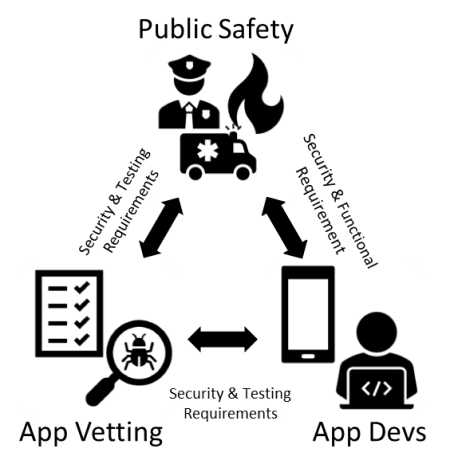

Mobile Application Developers and Mobile Application Vetting Tools

The third and final stakeholder we identified is made of up two distinct but related groups. The first group are the developers who will make the mobile app solutions for public safety mobile devices. The second are the tools used in the mobile app vetting space to automate the identification of mobile app vulnerabilities. The reason we consider these groups together as single stakeholder is because of the symbiotic relationship they share with public safety. In order to better fulfill public safety’s needs app developers must understand public safety’s domain specific cybersecurity requirements. Likewise, mobile app vetting tools require domain knowledge to tailor their testing and reporting to fit public safety’s needs.

Formalizing Public Safety Scenarios With Use Cases

Defining the Term Use Case

Use cases are used in many domains for many purposes. Loosely, they are used to describe relevant features of a scenario and how those features influence considerations for the audience. For a use case to be valuable, it must achieve two basic criteria. First, it must describe the scenario so that it is precise, accurate, and contains enough context given your audience. Second, it must highlight the features of the scenario that achieve your goal to your audience. Of course, how to fulfill these criteria is very dependent on the audience and the goal.

Consider for example the following use case, borrowed from NISTIR 8181 Incident Scenarios Collection for Public Safety Communications Incident Scenarios Collection for Public Safety Communications:

Region: Midwest: East North Central

Location: Rural

Time of year:Tuesday in May

A report was received at 14:45 of a small outdoor fire on the side of a small road. When responders arrived on scene, the fire had grown significantly, requiring multiple responding organizations.

Considerations:- Initial weather condition: temperature 82°F, humidity 26%.

- Initial winds were sustained at 12 mph (miles per hour), gusting to 21 mph out of the South-Southeast.

- Wind direction changed frequently, and in different directions.

- The area includes hundreds of buildings and primary residences.

- Citizens were evacuated.

- Various aircraft, tractor plows, and heavy dozers were resources used.

- Fire, police, EMS, energy/natural resources, forest service, and highway departments responded.

- Fire burned approximately 7400 acres.

- Fire was finally 100% contained 2 days later

This use case was borrowed from a document whose goal was to contextualize public safety tasks in terms of usability and emerging technology. We can see in this example some excellent features being identified: location, actors, temperature data, etc. However, there are a lot of gaps to fill when thinking of this in terms of which cybersecurity concerns this scenario may contain.

There is no one-size-fits all solution for describing all public safety use cases. The goal of this project was to improve the security of mobile apps for public safety by addressing our three core audiences described in the above section. To achieve this goal, we set out to design a loosely structured use case model. The remainder of this section describes how we structured this model in service achieving our success factors.

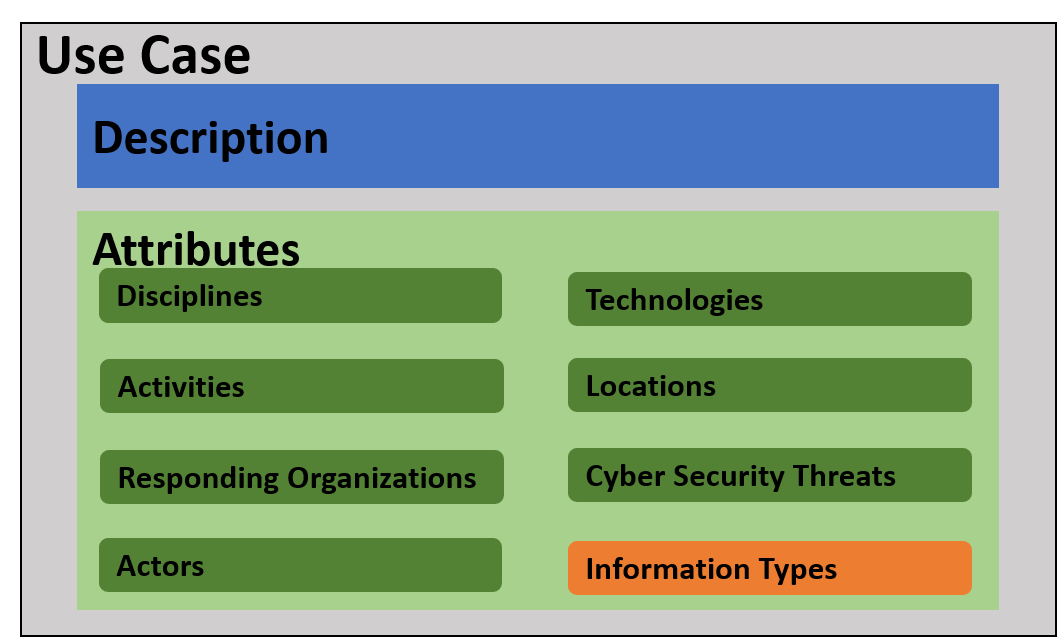

The anatomy of a Use Case for Cybersecurity

A use case consists of two components: a description and a collection of attributes. Figure 1 depicts how they each fit together.

Figure The parts of a use case

Use Case Description

The description is a prose description of the scenario for the use case. During our research, when we set out to find existing public safety use cases, this is often what we found. They could range from a single paragraph to multiple pages of description. While often unstructured, the description serves as the most important way to “tell the story” of the scenario in question. It serves as a narrative for the scenario itself. In our research, this was often lifted whole cloth from whatever source we were using.

Attributes

Attributes are named features of the scenario used to properly characterize the scenario in a use case. Attributes are identified by their attribute type. Attribute types are simply convenient labels that help to group similar attributes together. We identified eight attribute types that are important for accurately describing public safety use cases. The first six are simply name/description pairs and help group descriptive features of the scenario:

-

Discipline – a simple label that describes from which perspective (fire, EMS, and law enforcement) the use case is being told.

-

Activity – the operations being conducted by public safety during the use case

-

Responding Organization – what public safety entities are present or being considered as part of the use case

-

Actor – any individuals/roles that are part of the use case. Actors are any person, not just public safety official (patients, suspects, civilians, etc.).

-

Technology – any technologies that are a coordinated part of the scenario.

-

Location – a loose bucket intended to informally characterize where the scenario is taking place.

A seventh attribute type, cybersecurity threat was included in the model to identify any specific cyber threats that are part of the scenario. It was intended to be a place to identify scenarios that specifically contained targeted cyber-attacks.

The final attribute type, Information Type, serves as the container for the main cybersecurity guidance of the use case project. Information types have two purposes:

-

They are used to capture the classes of data that are central to the scenario depicted by the use case.

-

They contextualize that data’s risk in terms of confidentiality, availability, and integrity.

We characterize confidentiality, availability, and integrity in terms of their level of impact as described in FIPS 199:

Low - The loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability could be expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals.

Moderate - The loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability could be expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals.

High - The loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability could be expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals.

Finally, a use case should contain at least one information type and one discipline. Otherwise it can have any number of the remaining attributes.

Check out the Sample Data section for some example use cases.

Putting the Use Case Model in Action

In isolation, the model we have defined does not achieve our goal of providing public safety cyber security guidance. To continue advancing toward this goal, there are three more tasks we must complete.

-

Identifying and obtaining sources for meaningful public safety scenarios

-

Framing scenarios into our model

-

Curating a collection of use cases to support security guidance

Identifying Meaningful Public Safety Scenarios

Through our research we identified many potential sources for scenarios to populate our use cases. However, all aspects of a scenario can change depending on the perspective of each individual public safety organization. This includes both their own operational requirements as well as their cyber security requirements (and these will vary widely given the parameters of the situation).

That said, we had a few strategies for mining scenarios. They include:

-

Existing apps

-

Training material

-

Case Reports

-

Standard procedures

-

Formal ontologies

Framing Scenarios

Identifying meaningful and accurate public safety scenarios is a complicated task. Using the model we defined in Section 3 above, we needed a way to transpose scenarios we found into our formalized structure. We called this process framing. To frame a scenario we used the model as a lattice; using each of the attributes as a basis to interrogate the scenario’s description. The process of framing will differ depending on which audience perspective we are approaching the activity from. Below, we illustrate a hypothetical framing exercise from each of our core stakeholders.

Framing Example

This concept is best explained through an example. Let’s take a look a another example use case borrowed from the NIST usability document we mentioned above:

Situation

At 15:17, a 9-1-1 call from a cab driver indicated that the apartment building on a street in downtown is smoking and appears to be on fire. The dispatcher notified the fire department to send a fire engine and a fire ladder, and to send the battalion chief as the fire's incident commander. The nearest ambulance was alerted by the dispatcher to proceed to the scene. The dispatcher notified a neighboring jurisdiction to also send an engine to the fire.

Considerations

- The building had eight apartments on each of three floors.

- The main fire was discovered in a second floor apartment kitchen where an electric range was burning.

- Two adults and two children were trapped in the apartment suffering from smoke inhalation.

- Social media messages were used to post the status of the response

Using the scenario as a source, and relying on our model, we can begin to step through each of the attributes to formalize this use case. The information gathered here is by no means complete, but it captures the concept of what to think about when framing a use case.

This scenario is presented primarily from the point of view of the responding fire department. EMS also represented. Remember, the disciplines attribute is intended to capture which perspectives are being shown in the scenario. The absence of the law enforcement from this scenario isn’t to imply they are not present, just that there aren’t facets in this scenario that directly map to their perspective.

The responding organizations attribute may seem redundant, but it was included to add more depth to the disciplines attribute. Here, we list a generic fire department as the responding organization. In some scenarios, the differentiating between municipal, volunteer, private, or federal firefighting organizations might be relevant. Furthermore, there is no organization named that is providing emergency medical services, so we can’t narrow down this any further than is captured by the discipline.

Despite being a relatively short scenario, there are a lot of public safety activities we can identify. The scenario starts with a call to 9-1-1. The receiving dispatcher coordinates with the appropriate public safety resources (dispatch). We see the initiation of the Incident Management System (through the assignment of the incident commander).

At the scene, we see fire fighter engaging in fire fighting operations, evacuating the building. EMS is tending triaging and tending to those who are injured.

Finally, in a trend that is becoming more and more common, social media is used to spread information to the general public.

As with any real-world scenario, labeling actors in consistent and meaningful ways, can be a challenge. The actors identified above may not be an exhaustive, or precise as could be, but it illustrates the kinds of people present during a public safety scenario. Identifying these actors will help us to identify and contextualize information types later.

This scenario only really has two technologies. We can infer the cab driver making the originating 9-1-1 call is using a smartphone. The second is not named but is nearly ubiquitous to the Public Safety Access Point (PSAP): the Computer Aided Dispatch System (CAD System).

There weren’t any cyber security threats identified as part of the scenario, so we can leave this attribute set empty.

| Name | Confidentiality | Integrity | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| building floor plans | low | medium | medium |

| first responder assets | low | medium | medium |

| Patient Vitals | medium | medium | medium |

| patient birth date | medium | medium | medium |

| Blood Type | medium | medium | medium |

| Person Name | medium | medium | medium |

The information types identified here are the central part to our cybersecurity guidance. Remember we are attempting to classify the information types in terms of risk.

| building floor plans |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A structural diagram of the layout of a building | |||||||

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

operations data - information used directly by public safety command and control for active operations

|

|||||||

Building floor plans are mostly a matter of public record, thus making their confidentiality requirements quiet low. The integrity and availability of this data is moderate, as erroneous, out of date, or tempered information could endanger responders and interfere with their mission.

| first responder assets |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A catchall term used to describe the list of equipment, vehicles, and tools available to public safety during an incident. | |||||||

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

operations data - information used directly by public safety command and control for active operations

|

|||||||

The risk associated with the list of available public safety will vary greatly given the context of the scenario. In this situation, we regard the confidently risk as low, given that the exposing this information beyond the immediate operation doesn’t directly put anyone at risk. The integrity and availability of the information is rated at medium given as any disruption in this information stands to delay or disrupt public safety activities.

The following information types are examples of the kinds of information that is collected as part of providing medical care:

| Patient Vitals |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

Healthcare Information - Information gathered about a patient that is intended to be passed along to another healthcare entity. For example, information that may be loaded into a hospital's patient management system.

|

|||||||

| patient birth date |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The date of a person's birth. | |||||||

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

Person Type - A data type for a human being.

|

|||||||

| Blood Type |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A data concept for a blood group and RH factor of a person. | |||||||

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

Person Type - A data type for a human being.

|

|||||||

|

patient information - Information relating to a someone who is receiving medical care

|

|||||||

| Person Name |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A combination of names and/or titles by which a person is known. | |||||||

| Information Category & Supporting References | |||||||

|

Person Type - A data type for a human being.

|

|||||||

We rated the confidentially of these types of information to be moderate because of the HIPAA related concerns that may need to be taken into consideration while handling this type of data. Interference with the integrity or availability of this kind of data has the potential to harm patients or delay their care.

Curating Use Cases to Public Safety

Framing is a central part of the process for building a database of use cases. It would seem straight forward to simply find sources for a scenario, frame them, and publish the guidance contained in the newly minted use cases. However, as it is the most subjective, it is also the activity that can introduce the most bias and/or error in judgment on behalf of the framer. The cyber security concerns differ by discipline (fire, EMS, Law Enforcement) but also differ jurisdictionally at the local, state, and federal levels. Depending on the amount of information provided, the use cases may require a lot of gap-filling that NIST PSCR doesn’t itself have the resources to fill. The next section describes how we pivoted to try and address this concern.

Atlas – Putting Use Cases in Motion

Maintaining a centralized, up-to-date, and nuanced collection of public safety use cases is beyond the resources we had at our disposal. To solve this problem, we prototyped a sharable tool to allow organizations to frame their own use cases. We named this tool Atlas. Acting as both an interactive worksheet and a search engine for use cases, Atlas seeks to aide users with framing, searching, and cross-referencing public safety use cases.

A full description of Atlas can be found on its GitHub page. However, the primary features of Atlas can be highlighted by approaching each of these features from each of the audiences we described above.

Conclusions

Throughout this project, we were able to gather much useful information about how to structure public safety use cases and how we can translate the use cases into cybersecurity guidance. However, there is still a lot of work to be done to further develop the idea. During the project, we were able to share our ideas, test data, and prototype tools with various stakeholders. As with most projects, we had many stretch goals and ideas we did not have the time to fully realize. We will close out this discussion by summarizing the feedback we got and describing possible future work.

Building a Working Group

The first premise we had when planning this project was acknowledging that public safety’s mission is diverse, complex, and varied depending on what organizations are at play. As such, instead of taking the position that we would mandate data requirements to public safety, we opted to try and describe a process that could be taken up by those with the requisite domain knowledge. While we feel we have made a good start, it would be maximally beneficial for us to allow public safety itself to weigh in on what we have done so far, and to begin the real process of building a collection of use cases.

Use Case Model

Information Types and Security Classification

As mentioned in the model’s definition, an information type really consists of three parts: a name, a description, and a CIA security classification. We came to realize this is limiting in the following ways:

-

Having a flat description prevented us from linking information types borrowed from other structures sources (NIEM Information Model).

-

How do you account for types with the same or similar sounding names?

-

How do you account for information types whose security classification differs given the context? For example, some data may have higher ratings during an incident, but lower after the fact.

Adding Decision Points

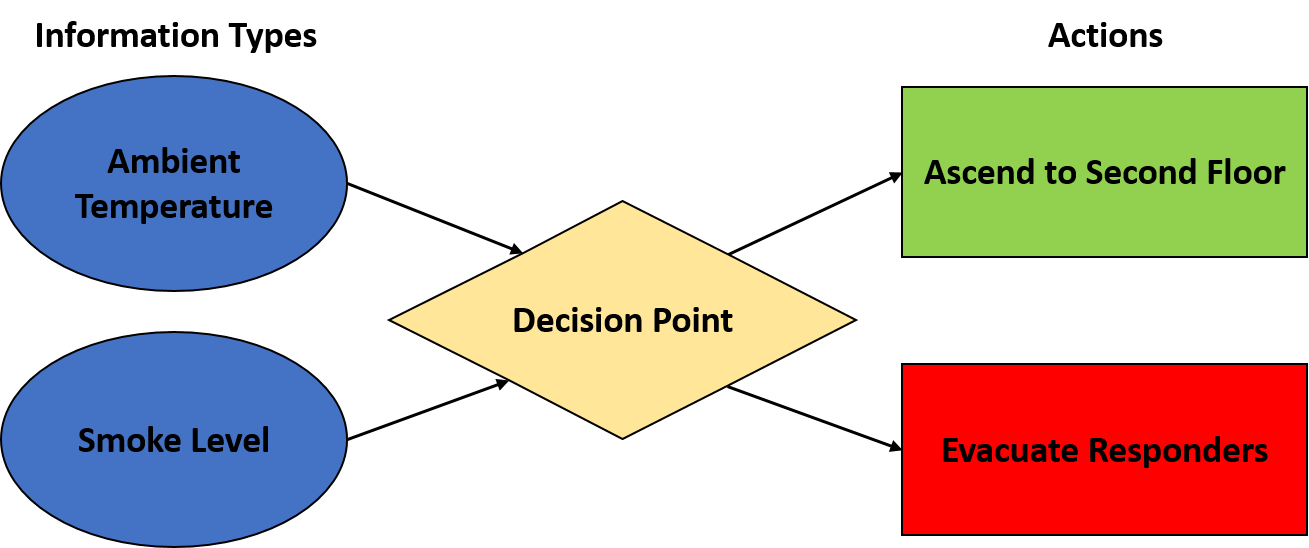

One piece of feedback we received was that use cases do not adequately account for how situations evolve over time. Specifically, they cannot capture the key inflection points that inform the actions of a first responder in a situation. The input to these decision points would be various information types whose actions would dictate the actions of a responder:

While we felt including this concept could be a powerful augmentation to our model, we were unsure how to properly capture it.

Needed Atlas Improvements

The Atlas tool itself is not feature complete and needs a lot of updates in order to be a useful tool for researchers and public safety alike. However, it captures a lot of what we were trying to achieve in terms of organization and visual display. That said, during the project, we identified a few reach goals/needed improvements we feel the tool would benefit from. We have listed them here for anyone looking to pick up the code base for further development.

-

Improved Searching – as the tool was designed with scale in mind, improved keyword/scoped searching is necessary.

-

Compositional Use Cases – being able to combine multiple use cases in order to make one larger use case. This would allow organizations to mix and match use cases from other users to better conform to their own situations.

-

Use Case/Data Export – Currently the data is stuck inside our document-oriented data store. While the database can export files in serialized JSON, a more readable or defined output mechanism could help users share data.

-

Report Generation – Ultimately, we envisioned this tool being able to output reports that could incorporated into NIST Risk assessments.

Mobile applications for public safety need to be evaluated for security vulnerabilities while they are being built, before deployment, and while they are being employed. Mobile application vetting services and tools bring value to public safety by helping to evaluate mobile application for security vulnerabilities. However, public safety has security requirements that are unique to those traditionally focused on by general purpose analysis tools. These security requirements are driven by uses cases the data types that will pass through public safety mobile apps.