# Problem Set-Up

Larry Aagesen ([@laagesen](https://github.com/laagesen)),

David Montiel,

Sourabh Kadambi ([@sourabhkadambi](https://github.com/sourabhkadambi)),

Sudipta Biswas ([@SudiptaBiswas](https://github.com/SudiptaBiswas))

After the phase-field model formulation is developed, implemented in code, and

verified, it can be set up to solve the scientific/engineering problem of

interest. The purpose of this page is to give guidance on some of the important

considerations when setting up your code to solve your specific problem,

organized in the following sections:

[Spatial dimension (1D vs. 2D vs. 3D)](#spatial-dimension)

[Initial conditions](#initial-conditions)

[Boundary conditions](#boundary-conditions)

[Interface width](#interface-width)

[Convergence](#convergence-studies)

[Impact of orientation](#impact-of-orientation)

[Kinetics and how long to run](#kinetics-and-how-long-to-run)

## Spatial Dimension

In setting up a phase-field simulation, it is important to understand the role

of spatial dimensions in the physics governing the problem, and how that might

impact the simulation results and its interpretation. This is particularly

important if simulations are being performed in reduced dimensions compared to

the actual dimension of the problem, which is a common practice employed to

reduce the computational costs.

It is likely that the physical behavior of a certain phenomenon might scale

differently in 1D, 2D and 3D. This could be related to the physical processes

in the bulk regions of the system or at the interfacial regions or both. For

instance, the amount of interfacial region relative to the bulk phase region

differs in 1D, 2D and 3D, and also governs many physical aspects of material

behavior.

Therefore, it is important to determine how reduced dimensionality might affect

predictions or comparison of simulation results with reality. In certain

situations, on the other hand, it might be appropriate to setup the problem in

reduced dimensions of 1D or 2D due to the inherent symmetry or directionality

in the problem. Moreover, for simple microstructure geometries, it might be

possible to setup the model in cylindrical or spherical coordinates, which can

allow the simplicity of 1D computations while also capturing 2D and 3D behavior

of the model accurately.

### Example

To demonstrate a case where simulation outcomes can significantly differ in

different dimensions, we consider the [single seed

case](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark8.ipynb/#Part-%28a%29)

of the [homogeneous

nucleation](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927025621000963?via%3Dihub)

benchmark problem. A simple phase-field model with a single non-conserved order

parameter describes an isothermal pure substance with one liquid phase (order

parameter = $0$) and one solid phase (order parameter = $1$). The nucleation

driving force for the solid phase is $\Delta f=\sqrt2/30$. The free energy of

the diffuse interface is $\gamma = 1/3\sqrt2$.

We consider a seed nucleus of $7.5$ unit radius in 2D and 3D. The 2D simulation

domain is of size $100\times100$, and the 3D simulation domain is of size $40

\times 40 \times 40$. The nucleus is centered at $x=y=z=0$. Uniform mesh of

element size $\Delta x = 0.09765$ is used. Neumann boundary conditions, given

by the zero normal-derivative of the order parameter, are applied on all domain

boundaries. The figure below shows the starting geometry of the nucleus in 2D

(left) and 3D (right).

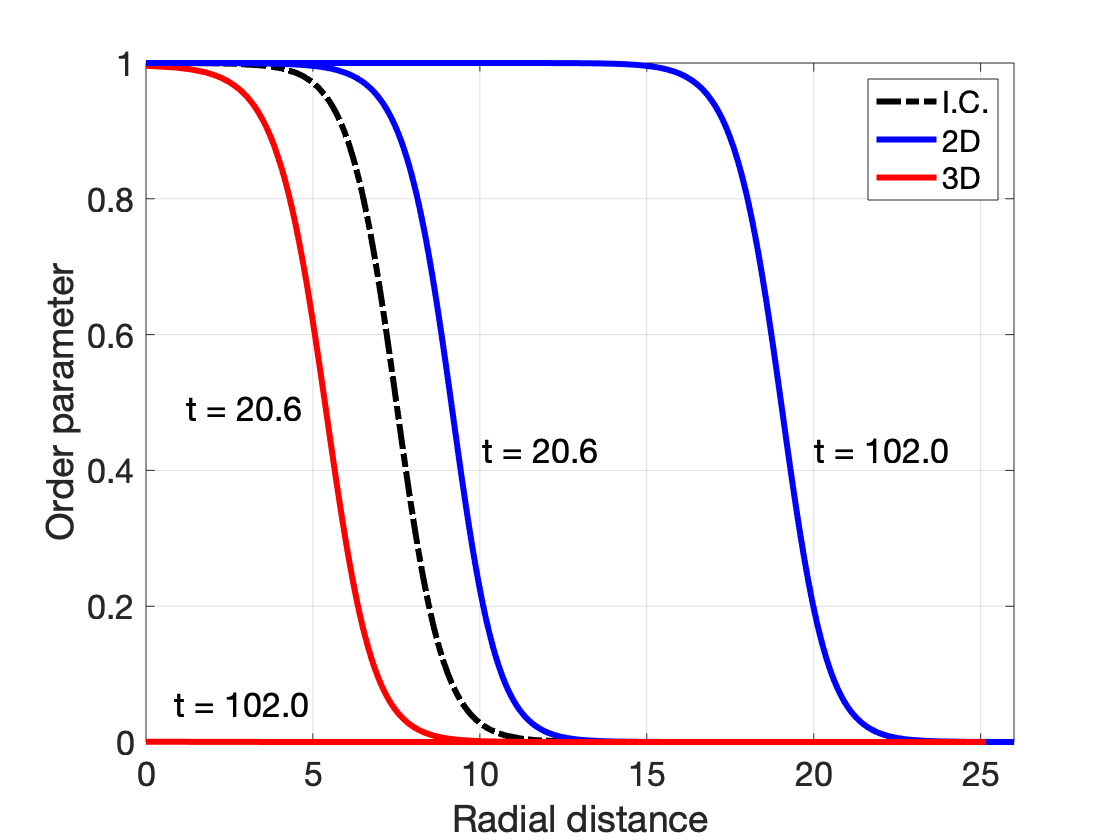

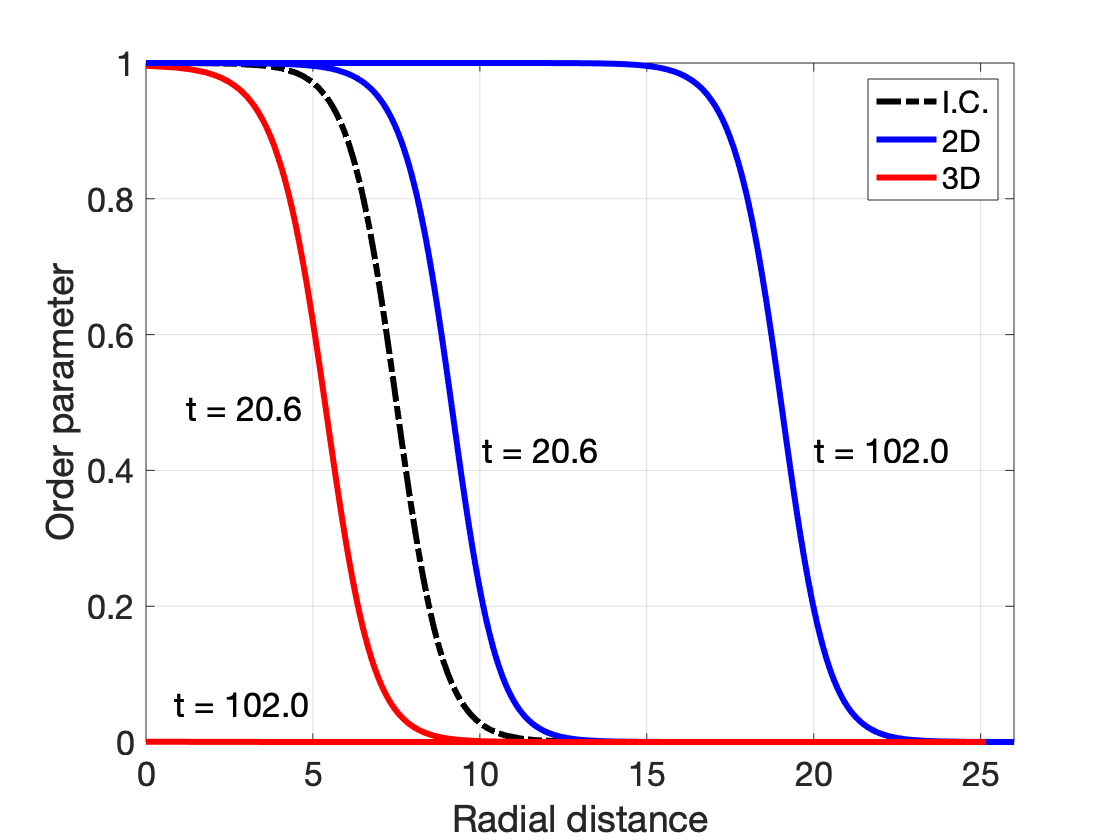

The time evolution of the order parameter, given by the Allen-Cahn equation,

was solved using the MOOSE framework. Details of the numerical method can be

found in [Wu _et al._ (2021)](

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927025621000963?via%3Dihub).

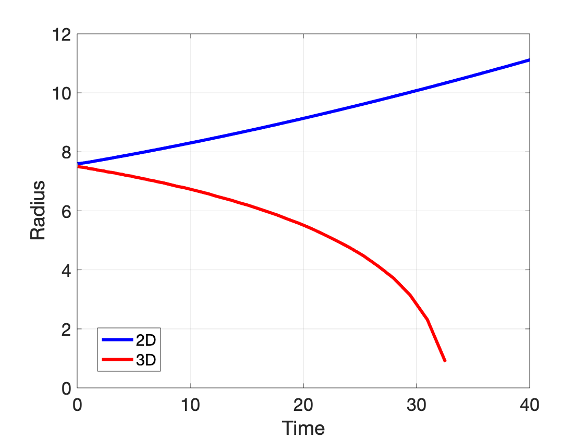

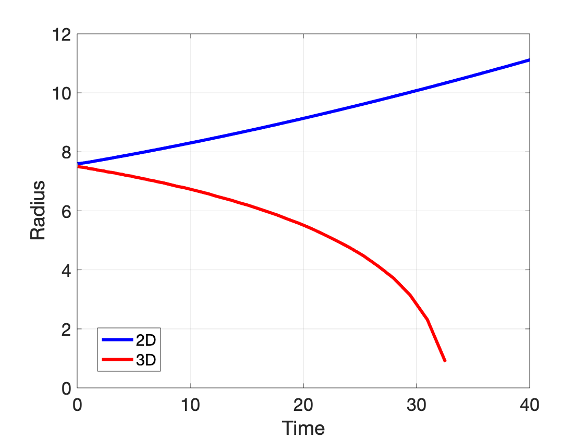

The simulations results of nucleus evolution are shown in the figures below:

(left) order parameter profile measured radially from the center of domain at

different evolution times; (right) radius as a function of evolution time. We

see that the seed of same starting radius $r_\circ = 7.5$ units evolves starkly

differently in 2D and 3D. While the nucleus grows in 2D, it shrinks and

dissolves in 3D.

The time evolution of the order parameter, given by the Allen-Cahn equation,

was solved using the MOOSE framework. Details of the numerical method can be

found in [Wu _et al._ (2021)](

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927025621000963?via%3Dihub).

The simulations results of nucleus evolution are shown in the figures below:

(left) order parameter profile measured radially from the center of domain at

different evolution times; (right) radius as a function of evolution time. We

see that the seed of same starting radius $r_\circ = 7.5$ units evolves starkly

differently in 2D and 3D. While the nucleus grows in 2D, it shrinks and

dissolves in 3D.

The role of dimensionality in homogeneous nucleation can be understood from the

classical nucleation theory where the solid-liquid interface is modeled as a

mathematically sharp interface. The interface is a 1D line in a 2D system and a

2D plane in a 3D system. The free energy of the nucleus particle $\Delta G(r)$

is a balance between the energy cost in forming the interface, and the energy

released due to the driving force in forming the bulk particle. For a 2D

system, $\Delta G(r) = 2\pi r\gamma - \pi r^2 \Delta f$. For a 3D system,

$\Delta G(r) = 4 \pi r^2 \gamma - (4 \pi /3) r^3 \Delta f$. When the rate of

change of free energy with respect to particle size is negative, the particle

is favored to grow; otherwise it will shrink and dissolve. By setting $d \Delta

G / d r = 0$, we obtain the critical radius as $r_c = \gamma/ \Delta f$ in 2D

and $r_c = 2\gamma/ \Delta f$ in 3D.

We can now apply the above sharp-interface analysis to our diffuse interface

approximation in the phase-field model. For the given model parameters, we

obtain $r_c = 5$ units in 2D and $r_c = 10$ units in 3D. In our simulation

setup of $r_\circ = 7.5$ units, $r_\circ$ $>$ $r_c$ in 2D, but $r_\circ < r_c$

in 3D. Therefore, the nucleus is favored to grow in 2D but shrinks in 3D as

observed in the simulations.

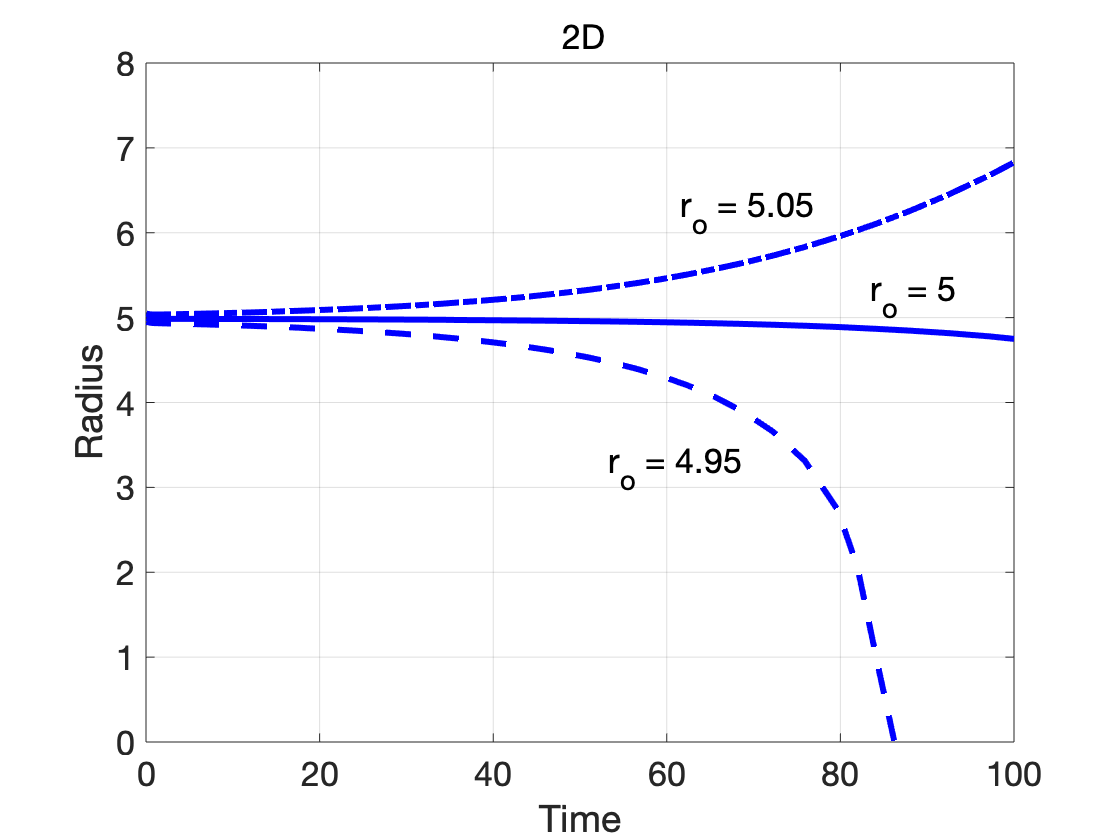

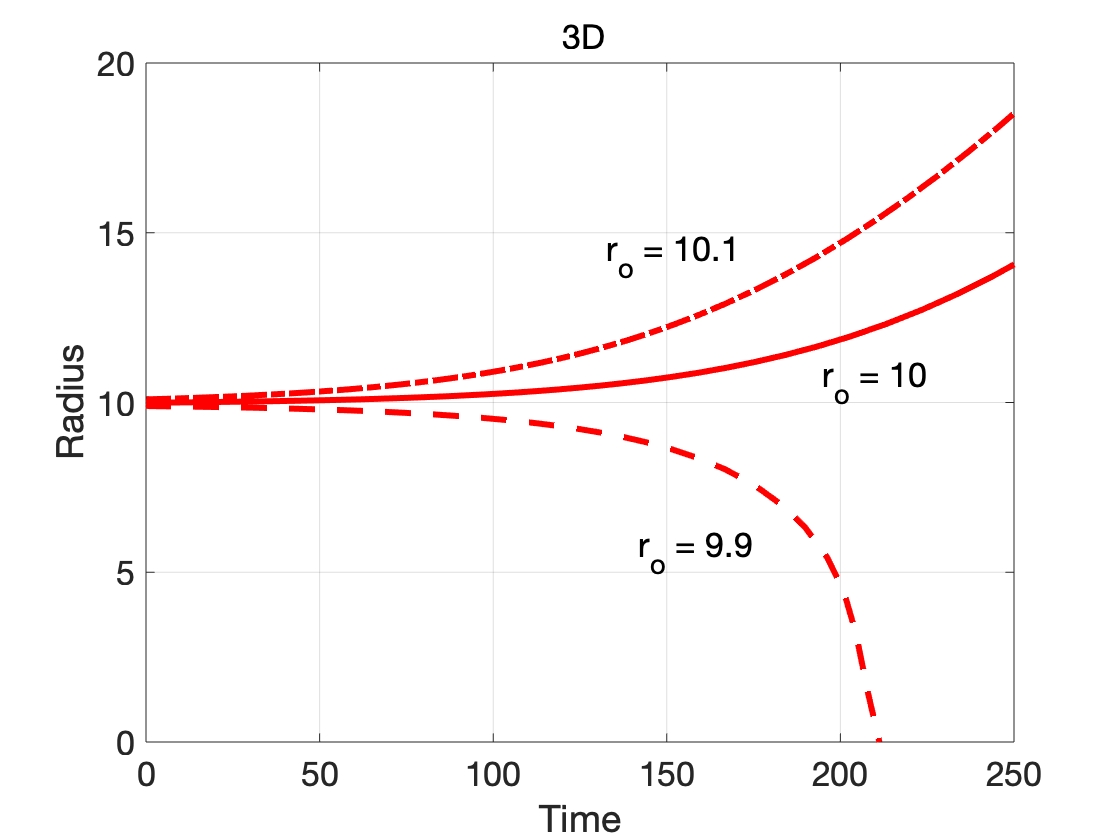

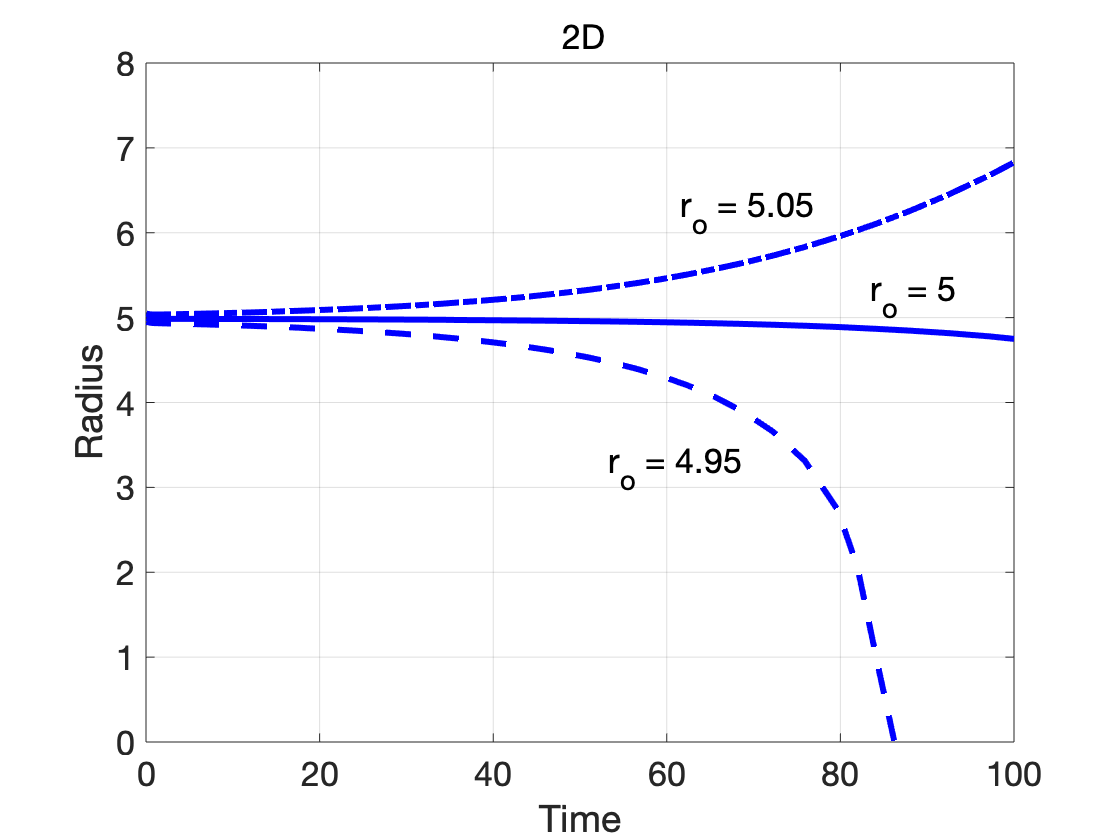

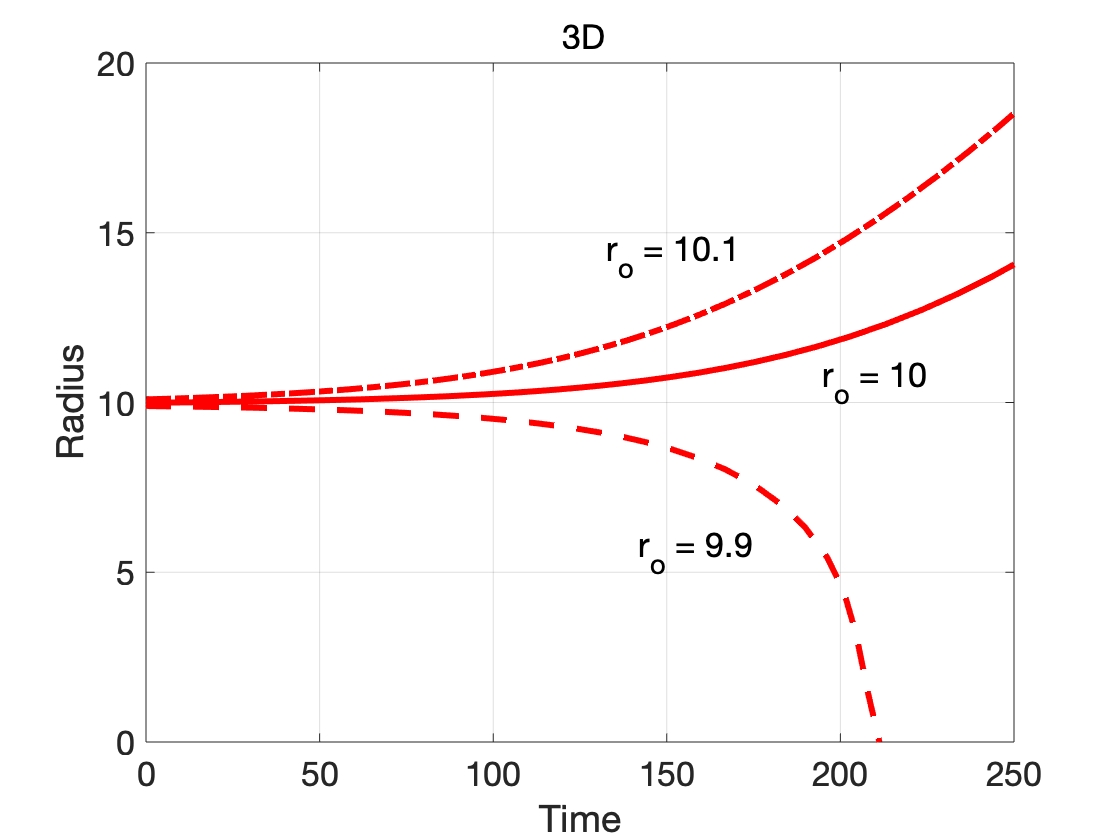

The dependence on dimensionality is further illustrated by considering cases

where the initial radius is close to the critical radius: $r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$,

$r_\circ = r_c$ and $r_\circ = 1.01 r_c$. The simulation results of radius

evolution are shown above for 2D (left) and 3D (right). As expected from the

the classical homogeneous nucleation theory, the sub-critical nucleus with

$r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$ shrinks and the super-critical nucleus with $r_\circ =

1.01 r_c$ grows.

Since the nucleus in the phase-field model is a diffuse-interface approximation

of the classical sharp interface nucleus, $r_\circ = r_c$ is fairly close to an

unstable equilibrium. Ideally, the radius would remain constant with

time. However, since the system is unstable, small numerical errors accumulate

with time, eventually leading to growth or shrinkage of the nucleus. During

initial time steps, the interface profile is expected to undergo some changes

from the starting profile due to equilibration. While the $tanh$ function is a

common choice for the initial condition of the interface, it is an exact

solution only for a planar interface, representative of a 1D scenario.

## Initial conditions

For simulations of the evolution of two or more phases, it is important to

anticipate the expected equilibrium state of the system given the initial

conditions. To do this, one needs the phase diagram as determined by the bulk

contribution of the free energy density.

For example, in simulating phase separation following spinodal decomposition,

it is common to define the initial state of the order parameter as a spatially

uniform field with an added small 'noisy' perturbation with small

amplitude. However, this order parameter must be within the spinodal region of

the phase diagram, i.e., the region where spontaneous decomposition leads to a

decrease in the free energy. Below we show two instances that demonstrate that

choosing different values for the baseline order parameter, $c_{0,\mathrm{base}}$, and

the same initial perturbation term, $\xi(\vec{r})$, for the initial conditions

of leads to different dynamics.

## Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions (BC) are required to solve for the governing equations in

all phase field simulations. In general, every field must have a defined BC at

every boundary of the system. The three most common types of boundary

conditions (BC) for phase field simulation are:

- Dirichlet BC: The value of a field is specified at the boundary. This type of

boundary condition is useful whenever we want to impose a value to an order

parameter or field at one or more boundaries. Some common examples include

setting a constant value for temperature to simulate a heat reservoir, or

setting a constant value for a solid/liquid order parameter to indicate a

fixed phase beyond the confines of the system.

- Neumann BC: The value of the spatial derivative of a field is specified at

the boundary. This type of boundary conditions is useful to specify fluxes of

fields at the boundary. For example, setting natural BC (a special case of

Neumann BC) for a field at the boundary enforces that the normal component of

gradient of that field is zero along that boundary. Therefore, if a flux for

that field is proportional to this gradient, natural BC is equivalent to

imposing zero flux at the boundary. This BC is convenient to ensure that the

field is conserved. In addition, natural BCs are useful to exploit known

symmetries in the morphology of domains: for example a spherical domain can

be simulated using a quarter (in 2D) or eighth of a system (in 3D) by placing

centering the sphere in a corner of the system and imposing natural BCs along

the boundaries that define the corner.

- Periodic BCs: The value of the field in a boundary with periodic BC matches

the value from the opposite boundary. These type of BCs are useful to

simulate periodic domains, but also to minimize boundary effects. since the

system does not interact with borders.

### Try different boundary conditions and check their impact

We used the results from Benchmark [Problem 1a](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(a)-Square-periodic)

and [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

to analyze the effect of boundary conditions. In addition, we solved for

Cahn-Hilliard dynamics under the same initial condition and simulation

parameters as problem 1 but using mixed boundary conditions, i.e., different

boundary conditions for each boundary. We compare the results for each case at

simulation time _t_ = 1000. The simulations were carried out in the PRISMS-PF

framework using a uniform square mesh with $N_x = N_y = 128$ linear elements

and a time step, $\Delta t$ = 0.005. The results are shown in the figure below.

As can be seen in the figure above, for periodic boundary boundaries the

$\alpha$ - $\beta$ domains are **continuous** on opposite sides of the

system. For no-flux boundaries, the $\alpha$ - $\beta$ interfaces are

**normal** to the boundary. For Dirichlet boundaries (bottom boundary of the

right panel), the value of _c_ is **fixed** along the boundary.

## Interface width

Phase-field modeling is a diffuse interface approach, meaning that interfaces

are represented by a smooth variation of one or more order parameters across

the interface. The width of the interface is a function of the model parameters

and the interface width is determined by model parameter choices. In some

cases, an analytical expression is available that relates interface width to

phase-field model parameters (such as free energy barrier height and gradient

energy coefficient, which also impact the interfacial energy). In other cases,

no analytical solution is available and the interface width must be

approximated or determined numerically based on parameter choices. Such details

are specific to the formulation being used.

Once the relationship between model parameters and interface width is

understood, an appropriate selection of interface width needs to be made (while

maintaining the correct interfacial energy for the system being studied). In

some cases, the interface width in the phase-field model can be chosen to match

the actual physical width of the interface being studied (such typically

sub-nanometer). However, resolving a physically realistic interface width

requires a sub-nanometer grid/mesh (grid/mesh convergence is described further

in the next section). Using a physically realistic interface width often makes

it computationally unfeasible to simulate systems large enough to be

statistically representative. Therefore, in many cases an interfacial width

that is much larger than the the physical width of an interface is used. In

these cases, a careful balance between computational efficiency and model

accuracy is needed; the interface width should be chosen to be small enough

that the physics of the system are accurately represented, while maintaining

adequate computational performance. A useful rule of thumb as a starting point

is that the interface width should be at least an order of magnitude smaller

than the smallest microstructural feature size of interest. Starting from this

guideline, simulations of microstructural evolution with varying interface

widths can be run to ensure that the choice of interface width does not affect

the simulation results. A small test problem may be useful for testing

convergence with respect to interface width; for example a shrinking circular

grain embedded in another grain may be used for testing convergence of a grain

growth model with respect to interface width, rather starting with large,

costly simulations of hundreds of grains.

## Convergence studies

### Carry out grid/mesh convergence study AFTER you have finalized your interfacial width.

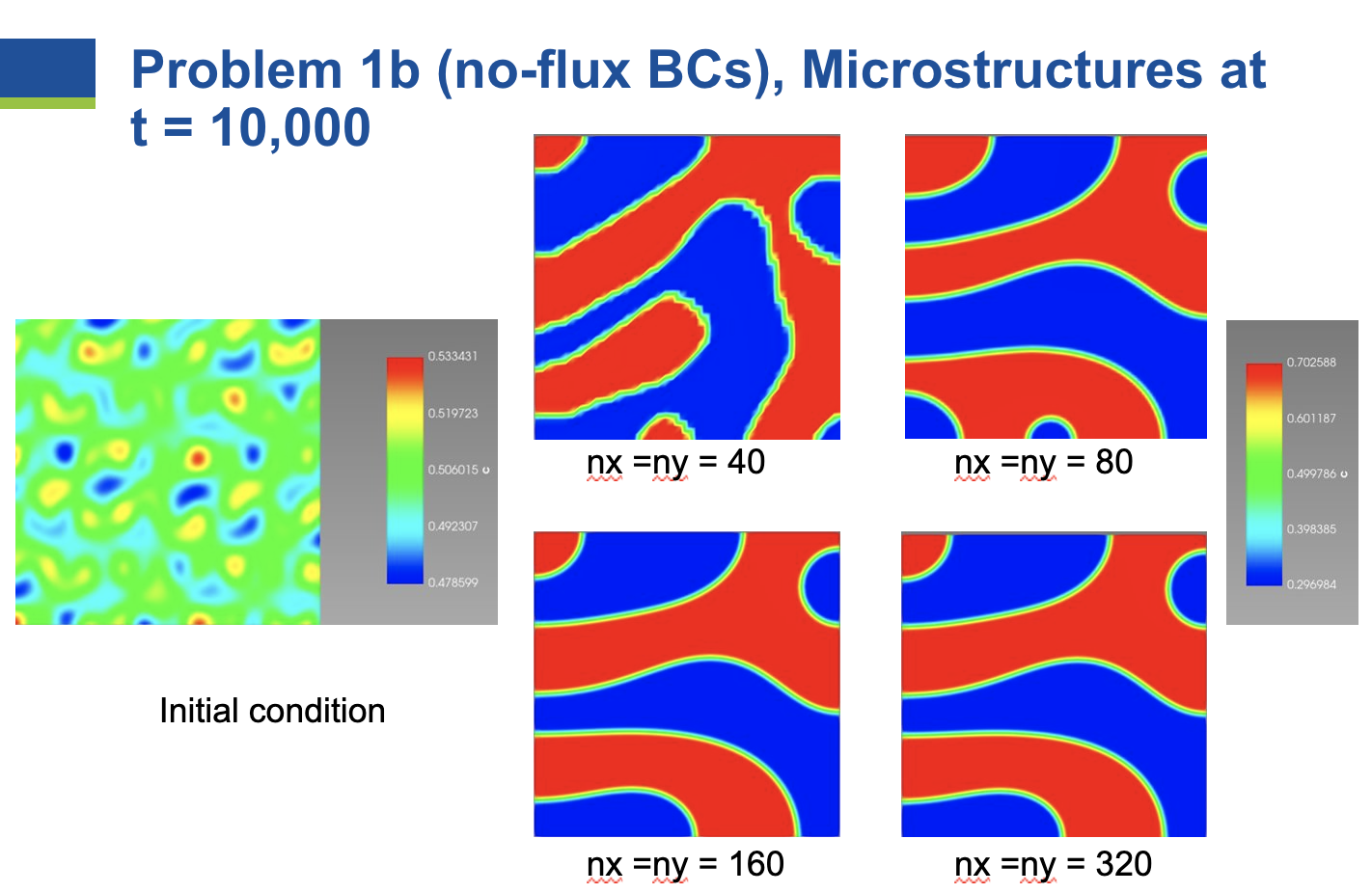

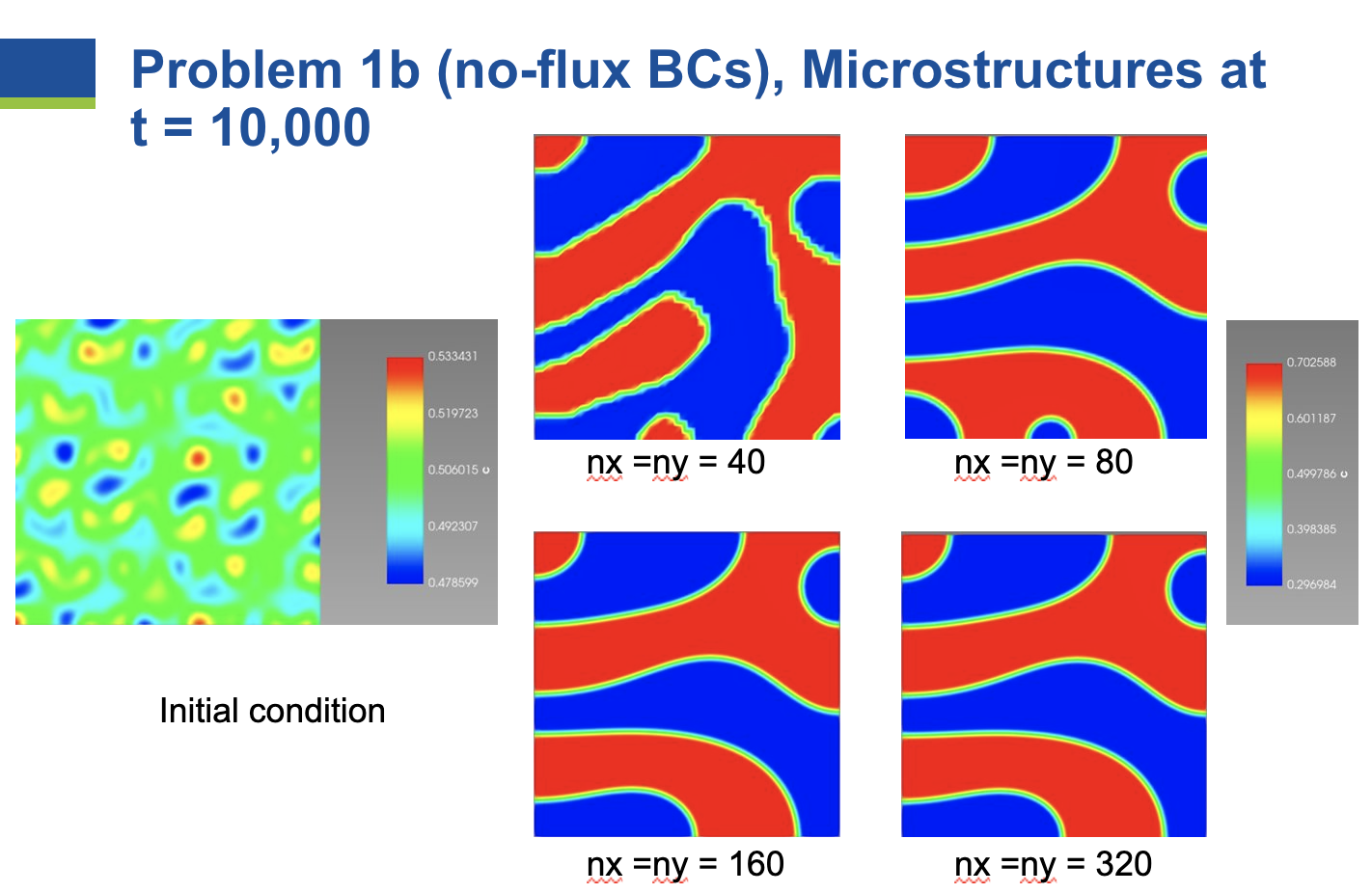

As an example of a mesh convergence study, we can consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. In this problem, which models spinodal decomposition

using the Cahn-Hilliard equation, the width of the diffuse interface is 4.47,

as defined by the Cahn-Hilliard equation and physical parameters in the problem

statement. Given this interface width, we need to ensure there are a sufficient

number of grid points (for finite difference schemes) or mesh elements (for

finite element or finite volume schemes) through the diffuse interface to

adequately resolve the variation of the composition order parameter.

In [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

a square domain with dimensions $200 \times 200$ and no-flux boundary

conditions is considered. An example of a mesh convergence study for this

problem using the MOOSE framework phase-field module (a finite element code) is

described. The $200 \times 200$ domain is discretized using increasing numbers

of elements $N_x$ in the $x$ direction and $N_y$ in the $y$ direction,

maintaining $N_x = N_y$ for square elements (using linear Lagrange shape

functions). The simulations with varying numbers of elements are run until a

significant amount of microstructural evolution has occurred. We need to

increase the number of elements until the microstructure at a fixed time no

longer changes with further increases in the number of elements; at this point

the simulation is converged with respect to the mesh resolution.

The simulation initial conditions and the microstructures at $t = 10,000$ are

shown in the figure below.

The dependence on dimensionality is further illustrated by considering cases

where the initial radius is close to the critical radius: $r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$,

$r_\circ = r_c$ and $r_\circ = 1.01 r_c$. The simulation results of radius

evolution are shown above for 2D (left) and 3D (right). As expected from the

the classical homogeneous nucleation theory, the sub-critical nucleus with

$r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$ shrinks and the super-critical nucleus with $r_\circ =

1.01 r_c$ grows.

Since the nucleus in the phase-field model is a diffuse-interface approximation

of the classical sharp interface nucleus, $r_\circ = r_c$ is fairly close to an

unstable equilibrium. Ideally, the radius would remain constant with

time. However, since the system is unstable, small numerical errors accumulate

with time, eventually leading to growth or shrinkage of the nucleus. During

initial time steps, the interface profile is expected to undergo some changes

from the starting profile due to equilibration. While the $tanh$ function is a

common choice for the initial condition of the interface, it is an exact

solution only for a planar interface, representative of a 1D scenario.

## Initial conditions

For simulations of the evolution of two or more phases, it is important to

anticipate the expected equilibrium state of the system given the initial

conditions. To do this, one needs the phase diagram as determined by the bulk

contribution of the free energy density.

For example, in simulating phase separation following spinodal decomposition,

it is common to define the initial state of the order parameter as a spatially

uniform field with an added small 'noisy' perturbation with small

amplitude. However, this order parameter must be within the spinodal region of

the phase diagram, i.e., the region where spontaneous decomposition leads to a

decrease in the free energy. Below we show two instances that demonstrate that

choosing different values for the baseline order parameter, $c_{0,\mathrm{base}}$, and

the same initial perturbation term, $\xi(\vec{r})$, for the initial conditions

of leads to different dynamics.

## Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions (BC) are required to solve for the governing equations in

all phase field simulations. In general, every field must have a defined BC at

every boundary of the system. The three most common types of boundary

conditions (BC) for phase field simulation are:

- Dirichlet BC: The value of a field is specified at the boundary. This type of

boundary condition is useful whenever we want to impose a value to an order

parameter or field at one or more boundaries. Some common examples include

setting a constant value for temperature to simulate a heat reservoir, or

setting a constant value for a solid/liquid order parameter to indicate a

fixed phase beyond the confines of the system.

- Neumann BC: The value of the spatial derivative of a field is specified at

the boundary. This type of boundary conditions is useful to specify fluxes of

fields at the boundary. For example, setting natural BC (a special case of

Neumann BC) for a field at the boundary enforces that the normal component of

gradient of that field is zero along that boundary. Therefore, if a flux for

that field is proportional to this gradient, natural BC is equivalent to

imposing zero flux at the boundary. This BC is convenient to ensure that the

field is conserved. In addition, natural BCs are useful to exploit known

symmetries in the morphology of domains: for example a spherical domain can

be simulated using a quarter (in 2D) or eighth of a system (in 3D) by placing

centering the sphere in a corner of the system and imposing natural BCs along

the boundaries that define the corner.

- Periodic BCs: The value of the field in a boundary with periodic BC matches

the value from the opposite boundary. These type of BCs are useful to

simulate periodic domains, but also to minimize boundary effects. since the

system does not interact with borders.

### Try different boundary conditions and check their impact

We used the results from Benchmark [Problem 1a](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(a)-Square-periodic)

and [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

to analyze the effect of boundary conditions. In addition, we solved for

Cahn-Hilliard dynamics under the same initial condition and simulation

parameters as problem 1 but using mixed boundary conditions, i.e., different

boundary conditions for each boundary. We compare the results for each case at

simulation time _t_ = 1000. The simulations were carried out in the PRISMS-PF

framework using a uniform square mesh with $N_x = N_y = 128$ linear elements

and a time step, $\Delta t$ = 0.005. The results are shown in the figure below.

As can be seen in the figure above, for periodic boundary boundaries the

$\alpha$ - $\beta$ domains are **continuous** on opposite sides of the

system. For no-flux boundaries, the $\alpha$ - $\beta$ interfaces are

**normal** to the boundary. For Dirichlet boundaries (bottom boundary of the

right panel), the value of _c_ is **fixed** along the boundary.

## Interface width

Phase-field modeling is a diffuse interface approach, meaning that interfaces

are represented by a smooth variation of one or more order parameters across

the interface. The width of the interface is a function of the model parameters

and the interface width is determined by model parameter choices. In some

cases, an analytical expression is available that relates interface width to

phase-field model parameters (such as free energy barrier height and gradient

energy coefficient, which also impact the interfacial energy). In other cases,

no analytical solution is available and the interface width must be

approximated or determined numerically based on parameter choices. Such details

are specific to the formulation being used.

Once the relationship between model parameters and interface width is

understood, an appropriate selection of interface width needs to be made (while

maintaining the correct interfacial energy for the system being studied). In

some cases, the interface width in the phase-field model can be chosen to match

the actual physical width of the interface being studied (such typically

sub-nanometer). However, resolving a physically realistic interface width

requires a sub-nanometer grid/mesh (grid/mesh convergence is described further

in the next section). Using a physically realistic interface width often makes

it computationally unfeasible to simulate systems large enough to be

statistically representative. Therefore, in many cases an interfacial width

that is much larger than the the physical width of an interface is used. In

these cases, a careful balance between computational efficiency and model

accuracy is needed; the interface width should be chosen to be small enough

that the physics of the system are accurately represented, while maintaining

adequate computational performance. A useful rule of thumb as a starting point

is that the interface width should be at least an order of magnitude smaller

than the smallest microstructural feature size of interest. Starting from this

guideline, simulations of microstructural evolution with varying interface

widths can be run to ensure that the choice of interface width does not affect

the simulation results. A small test problem may be useful for testing

convergence with respect to interface width; for example a shrinking circular

grain embedded in another grain may be used for testing convergence of a grain

growth model with respect to interface width, rather starting with large,

costly simulations of hundreds of grains.

## Convergence studies

### Carry out grid/mesh convergence study AFTER you have finalized your interfacial width.

As an example of a mesh convergence study, we can consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. In this problem, which models spinodal decomposition

using the Cahn-Hilliard equation, the width of the diffuse interface is 4.47,

as defined by the Cahn-Hilliard equation and physical parameters in the problem

statement. Given this interface width, we need to ensure there are a sufficient

number of grid points (for finite difference schemes) or mesh elements (for

finite element or finite volume schemes) through the diffuse interface to

adequately resolve the variation of the composition order parameter.

In [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

a square domain with dimensions $200 \times 200$ and no-flux boundary

conditions is considered. An example of a mesh convergence study for this

problem using the MOOSE framework phase-field module (a finite element code) is

described. The $200 \times 200$ domain is discretized using increasing numbers

of elements $N_x$ in the $x$ direction and $N_y$ in the $y$ direction,

maintaining $N_x = N_y$ for square elements (using linear Lagrange shape

functions). The simulations with varying numbers of elements are run until a

significant amount of microstructural evolution has occurred. We need to

increase the number of elements until the microstructure at a fixed time no

longer changes with further increases in the number of elements; at this point

the simulation is converged with respect to the mesh resolution.

The simulation initial conditions and the microstructures at $t = 10,000$ are

shown in the figure below.

As the number of elements in each direction is increased from 40 to 80 to 160,

changes in the microstructure are observed. However, once the number of

elements increases to 320, no further changes are observed in the

microstructure. Therefore, the problem is converged with respect to mesh

resolution at $N_x = N_y = 160$. For this number of elements, each element has

size $\Delta x = \Delta y$ = 200 / 160 = 1.25. Therefore, the number of

elements through the diffuse interface width is 4.47 / 1.25 = 3.6. Practical

experience in the phase-field community has shown that somewhere between 3 to 5

elements through the interface are usually required to obtain mesh convergence;

however, the appropriate resolution is problem-specific, and convergence should

be tested for the specific physics and parameters at hand.

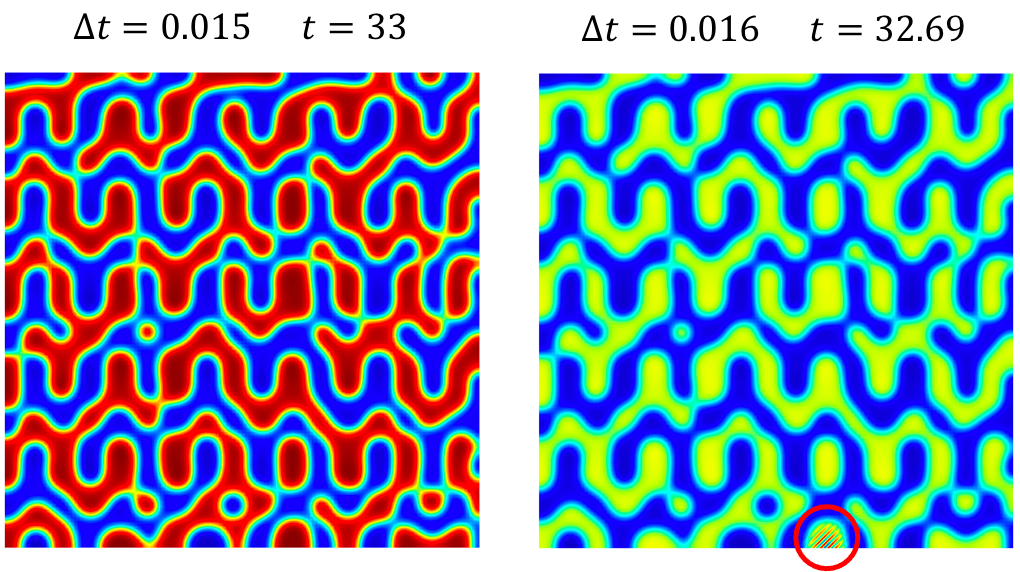

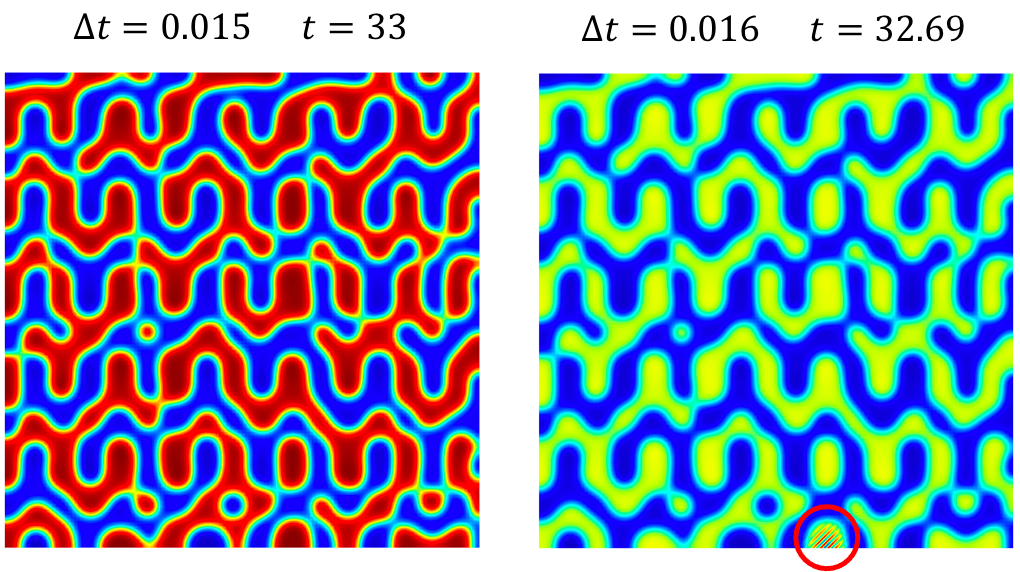

### Carry out time step convergence studies. Try higher-order schemes, adaptive time stepping, etc. For explicit time integration, know your stability limit.

For codes that use explicit time integration, there is a maximum value of the

time step beyond which the solution becomes numerically unstable. This

stability limit can be determined by the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL)

condition and, in general, it strongly depends on the order of the spatial

derivatives. Below we show the simulation results of [Benchmark Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

using time step values slightly below and slightly above the stability

limit. We employed a forward Euler time-integration scheme and spatially

discretized the system using $128 \times 128$ first order elements. The

simulations were performed in the PRISMS-PF framework. The left panel of the

figure below shows a snapshot of the concentration at time $t=33$, which was

obtained using a stable time step of $\Delta t=0.015$. If the time step is

increased to $\Delta t=0.016$, the time step goes above the stability

limit. The right panel shows the concentration at time $t \simeq 32.39$ for

$\Delta t=0.016$ and features a numerical instability that appears near the

bottom boundary. After only four time steps the amplification of this

instability caused the simulation to fail.

As the number of elements in each direction is increased from 40 to 80 to 160,

changes in the microstructure are observed. However, once the number of

elements increases to 320, no further changes are observed in the

microstructure. Therefore, the problem is converged with respect to mesh

resolution at $N_x = N_y = 160$. For this number of elements, each element has

size $\Delta x = \Delta y$ = 200 / 160 = 1.25. Therefore, the number of

elements through the diffuse interface width is 4.47 / 1.25 = 3.6. Practical

experience in the phase-field community has shown that somewhere between 3 to 5

elements through the interface are usually required to obtain mesh convergence;

however, the appropriate resolution is problem-specific, and convergence should

be tested for the specific physics and parameters at hand.

### Carry out time step convergence studies. Try higher-order schemes, adaptive time stepping, etc. For explicit time integration, know your stability limit.

For codes that use explicit time integration, there is a maximum value of the

time step beyond which the solution becomes numerically unstable. This

stability limit can be determined by the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL)

condition and, in general, it strongly depends on the order of the spatial

derivatives. Below we show the simulation results of [Benchmark Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

using time step values slightly below and slightly above the stability

limit. We employed a forward Euler time-integration scheme and spatially

discretized the system using $128 \times 128$ first order elements. The

simulations were performed in the PRISMS-PF framework. The left panel of the

figure below shows a snapshot of the concentration at time $t=33$, which was

obtained using a stable time step of $\Delta t=0.015$. If the time step is

increased to $\Delta t=0.016$, the time step goes above the stability

limit. The right panel shows the concentration at time $t \simeq 32.39$ for

$\Delta t=0.016$ and features a numerical instability that appears near the

bottom boundary. After only four time steps the amplification of this

instability caused the simulation to fail.

Codes that use implicit time stepping schemes may have fewer restrictions with

respect to stability as time step size is increased, depending on the

problem. However, discretization error still occurs in implicit schemes and

increases with the size of the time step taken. Therefore, a convergence study

should be carried out to ensure that the size of the time step does not affect

the simulation results. As an example, we can again consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. [Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

was solved with the phase-field module from the MOOSE framework using $N_x =

N_y = 160$. The results are shown below. The microstructure at $t = 1000$

remains the same for $\Delta t = 0.1$, $\Delta t = 0.25$, and $\Delta t =

0.5$. Some differences in the microstructure are observed at $\Delta t = 1$,

and further differences become apparent at $\Delta t = 4$. In practice, it is

recommended to start with a given time step and gradually decrease it until no

changes are apparent with further decreases in time step size.

Adaptive time stepping can be useful to increase the time step size during time

periods in the simulation where there are fewer microstructural changes,

particularly for codes that use implicit time stepping schemes. However,

convergence must still be checked for the parameters of the time stepping

scheme being used. An example is the IterationAdaptiveDt time stepping scheme

used in the MOOSE framework. This scheme attempts to increase or decrease the

time step to keep the solver using a certain number of nonlinear iterations

(controlled by the parameter `optimal_iterations`), within a window or plus or

minus the parameter `iteration_window`. Higher values of `optimal_iterations`

parameter result in higher time steps, and with that comes the risk of

discretization error changing simulation results. As shown in the following,

for [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

`optimal_iterations` values of 6 or 8 gave results consistent with the

converged time step of 0.5, but when `optimal_iterations` was significantly

increased to 15, changes in the microstructure resulted.

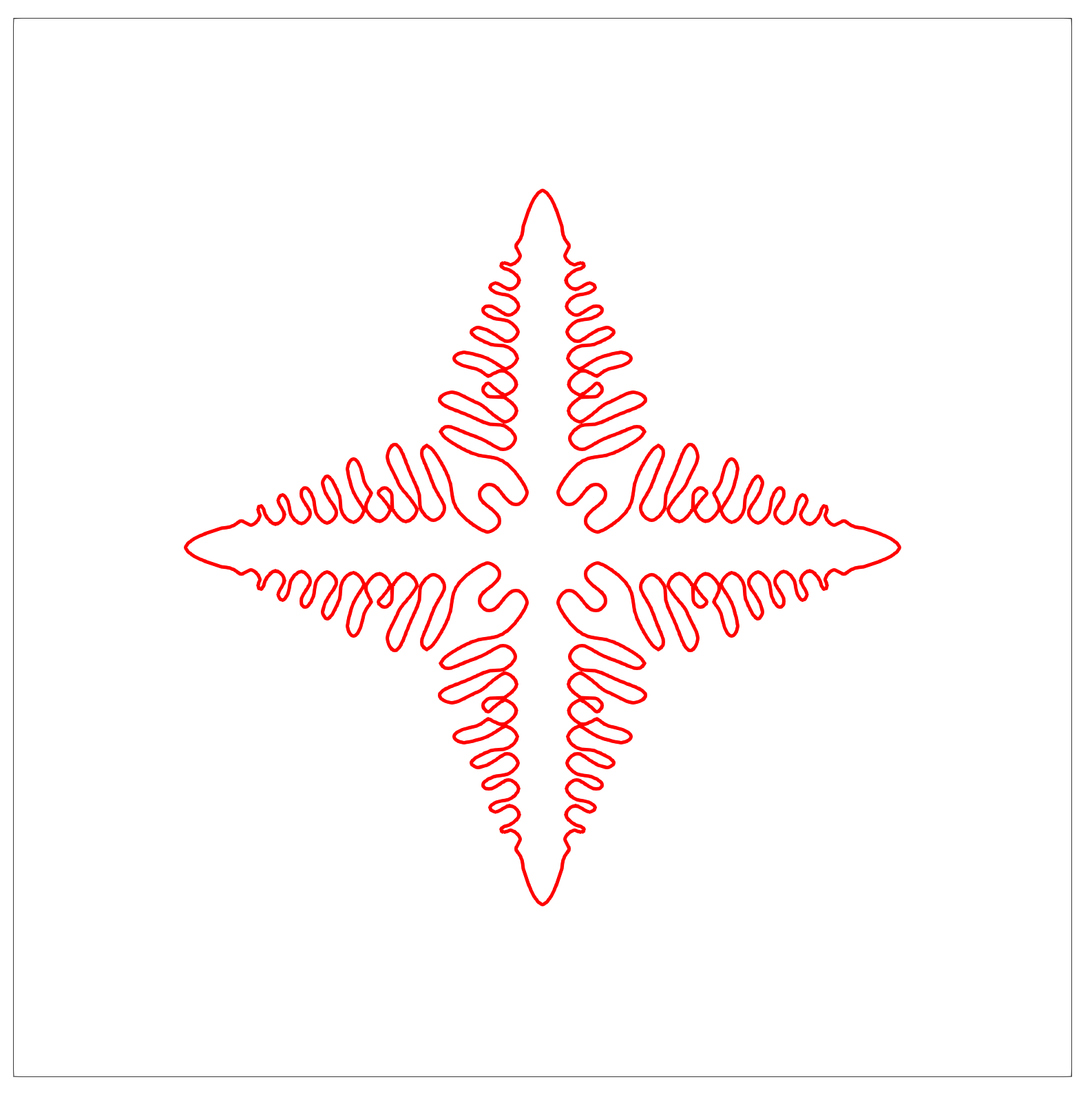

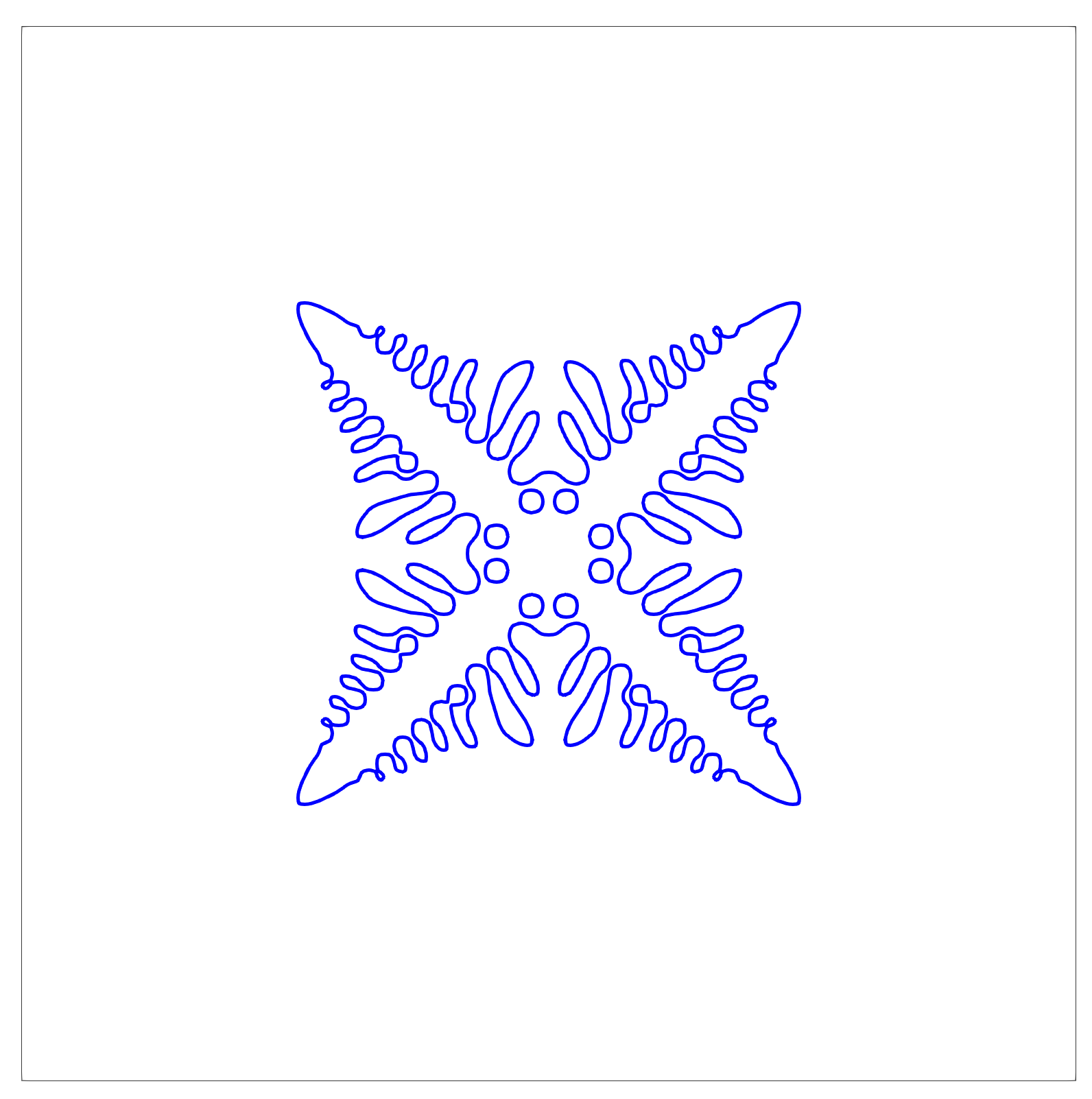

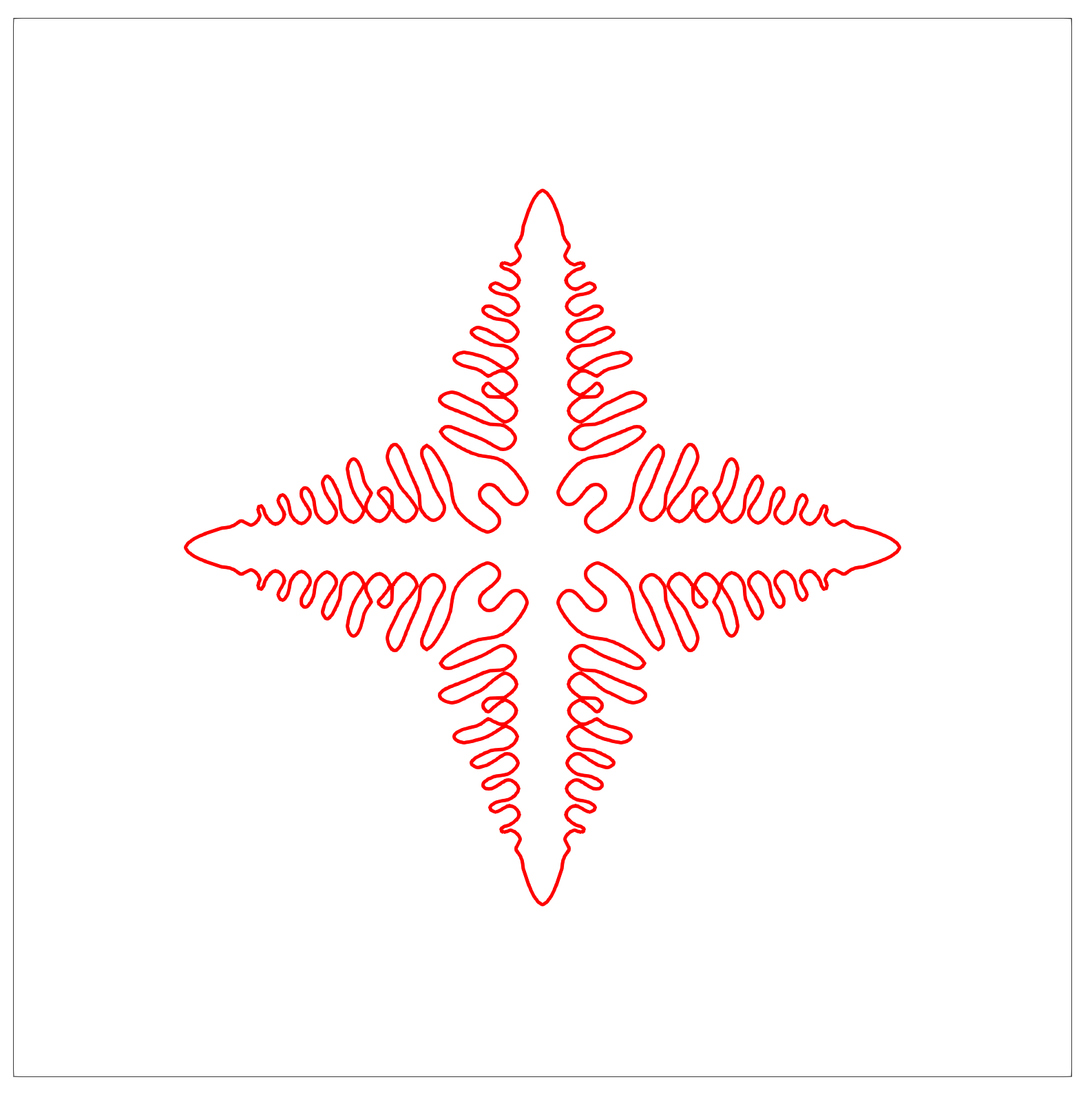

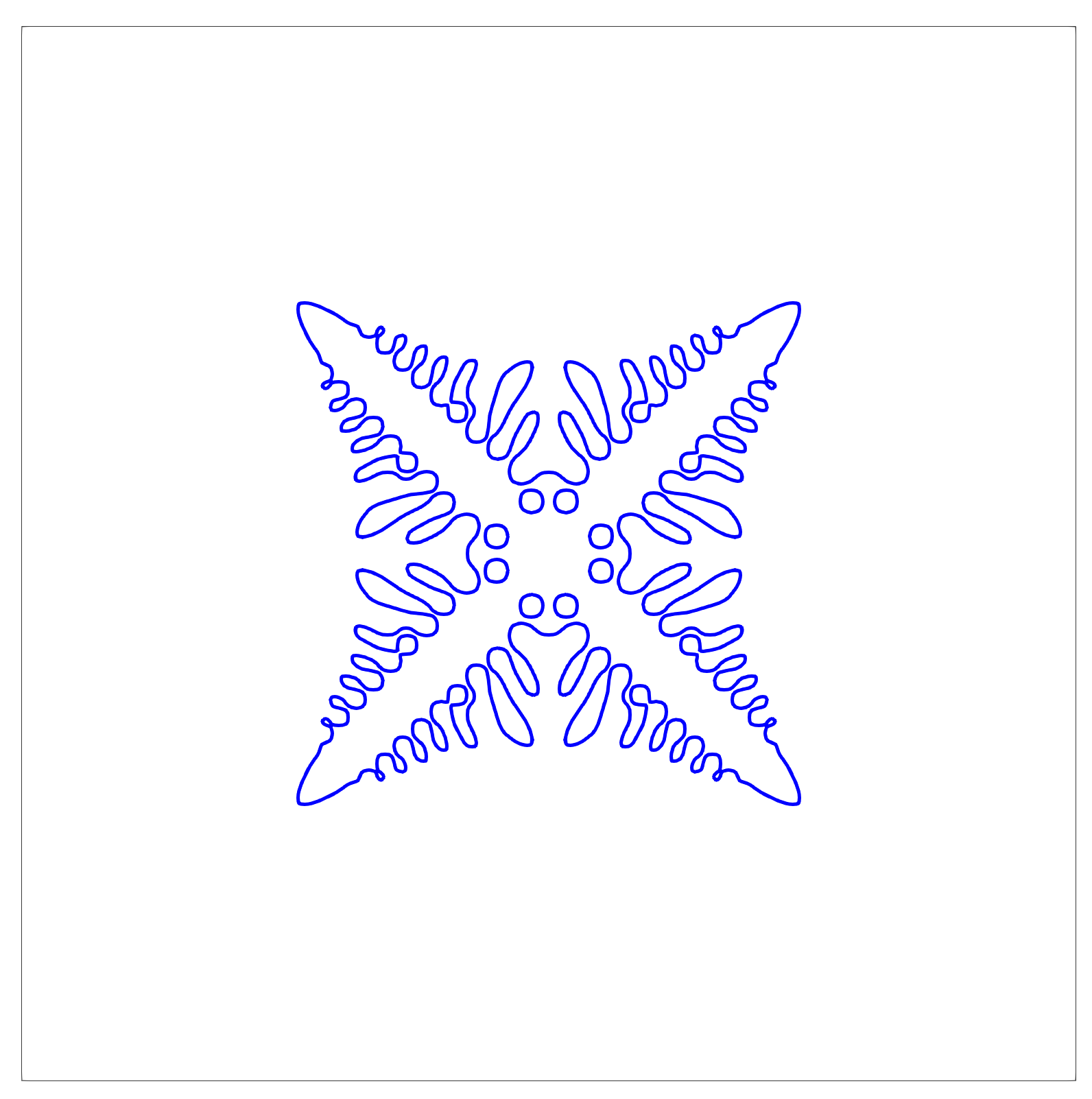

## Impact of Orientation

Oftentimes, the results of the phase field simulations are sensitive to the

orientation and alignment of the key microstructural features with the

mesh/grid points. To demonstrate this we pick a simple solidification problem

with dendritic structure formation. In this case, we utilize the solidification

[example](https://github.com/idaholab/moose/blob/next/modules/phase_field/examples/anisotropic_interfaces/snow.i)

from the MOOSE-based phase field module. This example problem can quickly

demonstrate dendritic structure formation including the formation of secondary

dendritic arms in a computationally cost-effective manner. Here, we use 4-fold

symmetry of the structure and vary the reference angles to misorient the

dendritic arms with respect to the mesh. Dendritic structures corresponding to

0 and 45 degree reference angle is presented below:

Codes that use implicit time stepping schemes may have fewer restrictions with

respect to stability as time step size is increased, depending on the

problem. However, discretization error still occurs in implicit schemes and

increases with the size of the time step taken. Therefore, a convergence study

should be carried out to ensure that the size of the time step does not affect

the simulation results. As an example, we can again consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. [Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

was solved with the phase-field module from the MOOSE framework using $N_x =

N_y = 160$. The results are shown below. The microstructure at $t = 1000$

remains the same for $\Delta t = 0.1$, $\Delta t = 0.25$, and $\Delta t =

0.5$. Some differences in the microstructure are observed at $\Delta t = 1$,

and further differences become apparent at $\Delta t = 4$. In practice, it is

recommended to start with a given time step and gradually decrease it until no

changes are apparent with further decreases in time step size.

Adaptive time stepping can be useful to increase the time step size during time

periods in the simulation where there are fewer microstructural changes,

particularly for codes that use implicit time stepping schemes. However,

convergence must still be checked for the parameters of the time stepping

scheme being used. An example is the IterationAdaptiveDt time stepping scheme

used in the MOOSE framework. This scheme attempts to increase or decrease the

time step to keep the solver using a certain number of nonlinear iterations

(controlled by the parameter `optimal_iterations`), within a window or plus or

minus the parameter `iteration_window`. Higher values of `optimal_iterations`

parameter result in higher time steps, and with that comes the risk of

discretization error changing simulation results. As shown in the following,

for [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

`optimal_iterations` values of 6 or 8 gave results consistent with the

converged time step of 0.5, but when `optimal_iterations` was significantly

increased to 15, changes in the microstructure resulted.

## Impact of Orientation

Oftentimes, the results of the phase field simulations are sensitive to the

orientation and alignment of the key microstructural features with the

mesh/grid points. To demonstrate this we pick a simple solidification problem

with dendritic structure formation. In this case, we utilize the solidification

[example](https://github.com/idaholab/moose/blob/next/modules/phase_field/examples/anisotropic_interfaces/snow.i)

from the MOOSE-based phase field module. This example problem can quickly

demonstrate dendritic structure formation including the formation of secondary

dendritic arms in a computationally cost-effective manner. Here, we use 4-fold

symmetry of the structure and vary the reference angles to misorient the

dendritic arms with respect to the mesh. Dendritic structures corresponding to

0 and 45 degree reference angle is presented below:

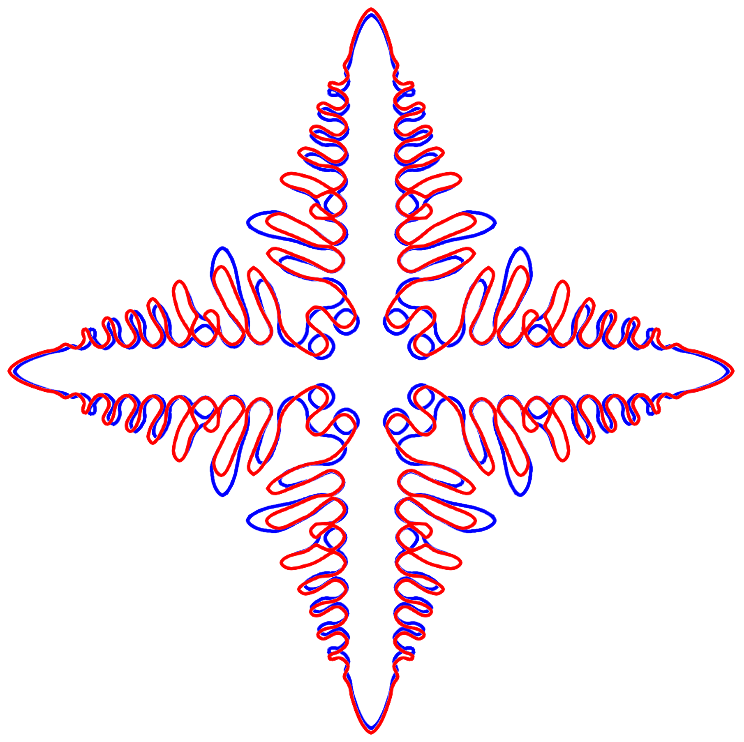

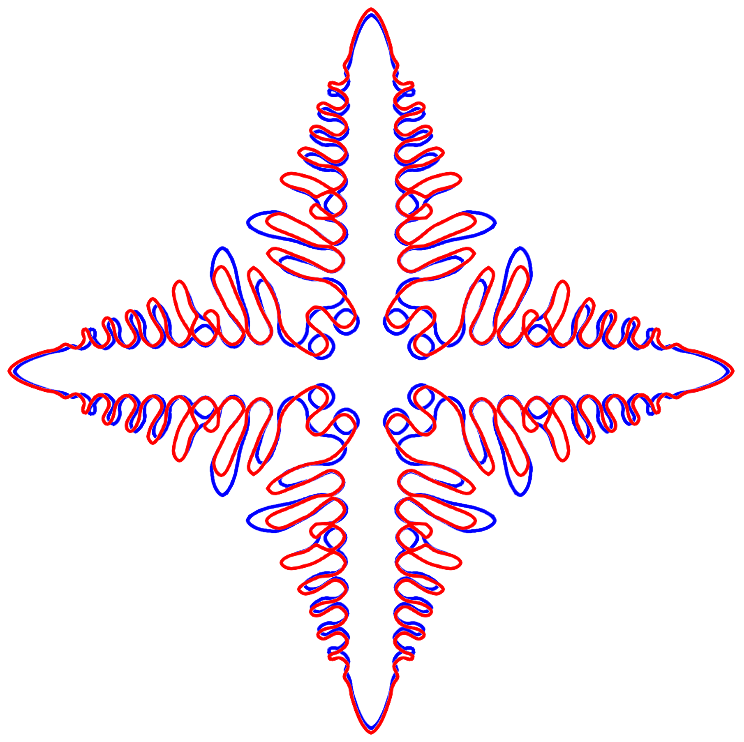

It is noteworthy that the shape of the dendrite varies with orientation (as

observed by the difference in the dendrite center). For better comparison, we

rotate the $45^{\circ}$ dendrite to align the primary dendrite arms with the

reference orientation dendrite:

It is noteworthy that the shape of the dendrite varies with orientation (as

observed by the difference in the dendrite center). For better comparison, we

rotate the $45^{\circ}$ dendrite to align the primary dendrite arms with the

reference orientation dendrite:

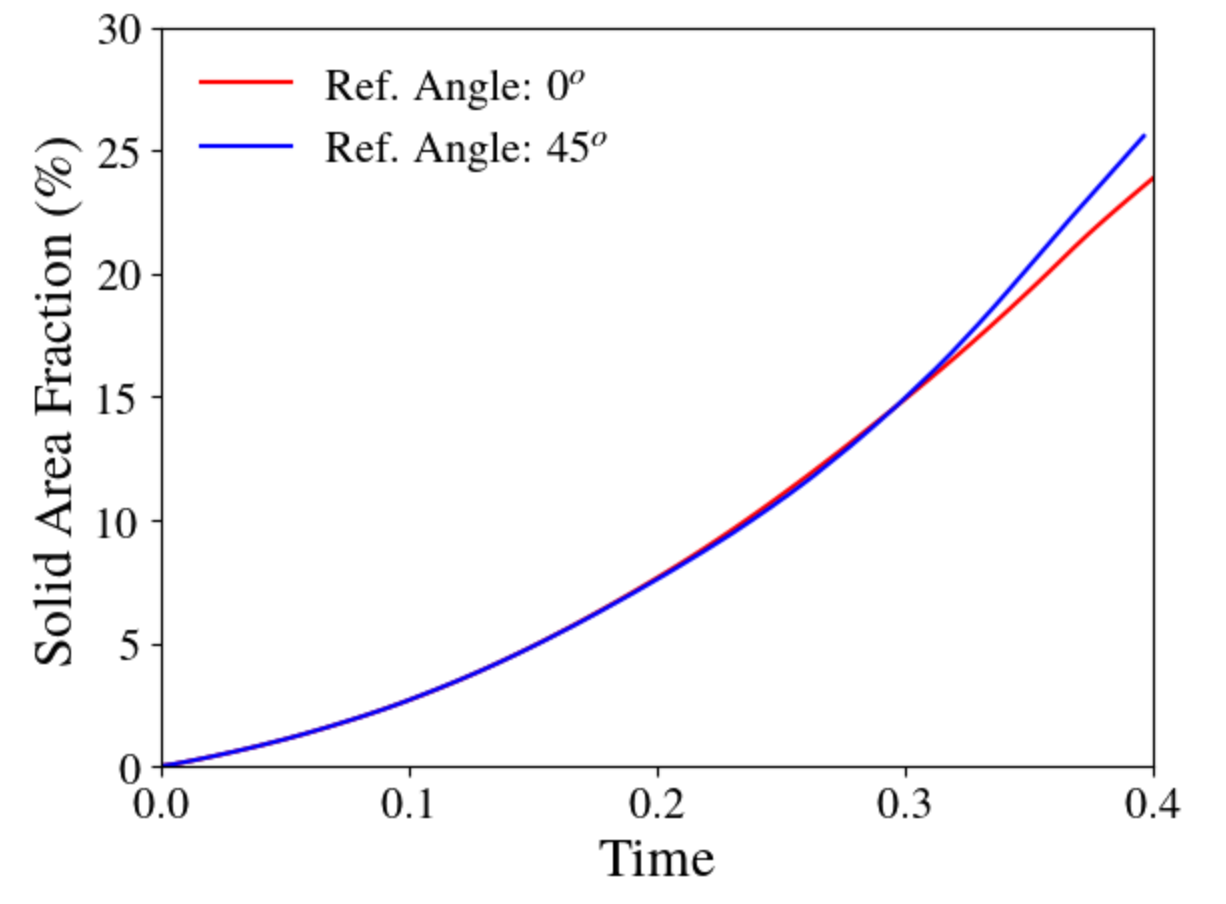

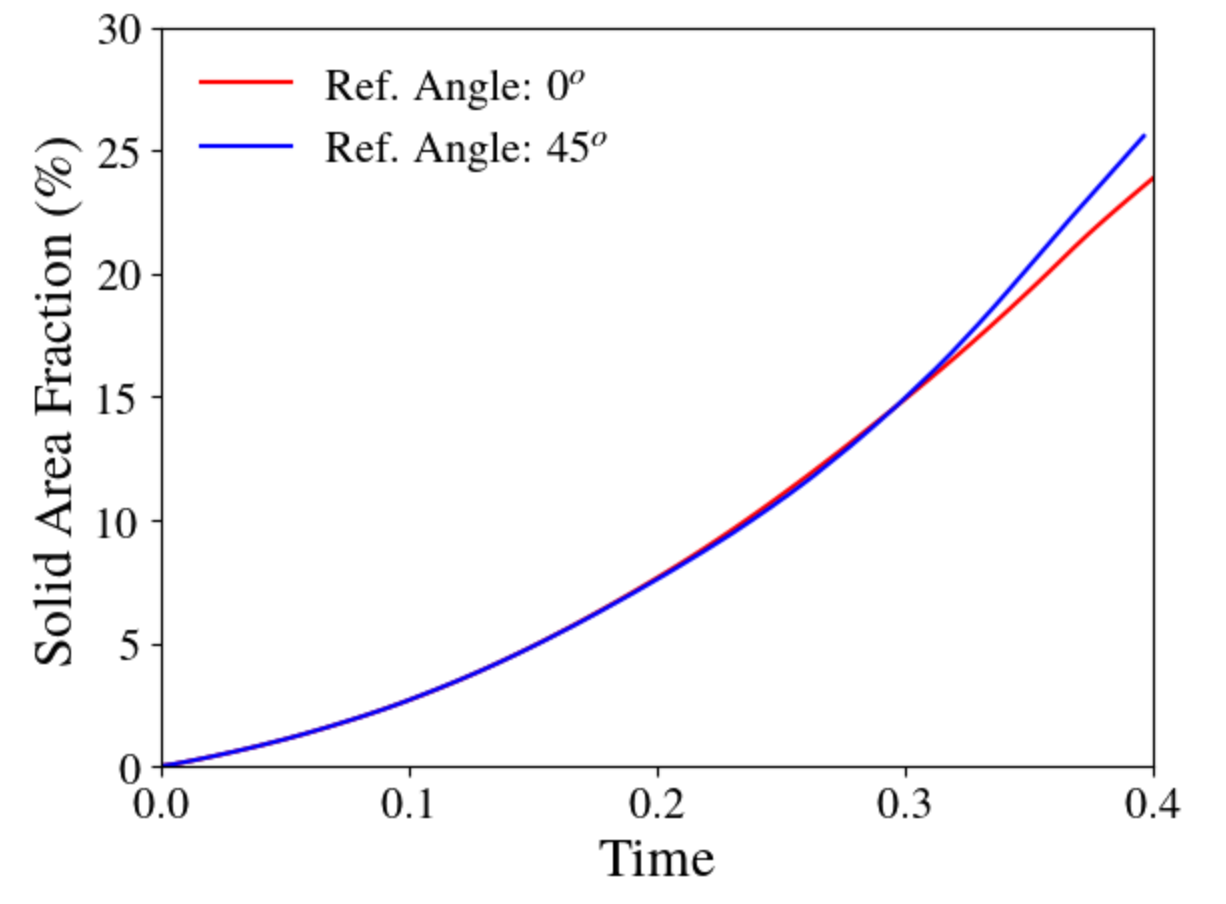

This highlights the slight differences between the dendrite shapes, especially

the center and the secondary dendritic arms. Additionally, the growth rate of

the solid also varies with orientation as observed by the change in solid area

fraction over time:

This highlights the slight differences between the dendrite shapes, especially

the center and the secondary dendritic arms. Additionally, the growth rate of

the solid also varies with orientation as observed by the change in solid area

fraction over time:

Thus, it is important to evaluate the effect of orientation on the results by

misaligning the grids. Furthermore, these effects are influenced by the

discretization of the mesh. Hence, it is important to ensure that the mesh is

refined enough to properly resolve the interfaces (if necessary, run a mesh

convergence study). For more information about strategies to simulate multiple

dendrites with varying orientation, please refer to examples by Biswas et

al. [[1]](#1), Warren et al. [[2]](#2), Dorr et al. [[3]](#3), Ofori-Opoku et

al. [[4]](#4), and Pusztai et al. [[5]](#5), among others.

## Kinetics and how long to run

The amount of time the simulation should be run depends on the science or

engineering question to be answered, and on the system being studied. For many

classic phase-field problems such as grain growth and coarsening, a

characteristic feature size of the system increases with time, and the progress

of microstructural evolution slows as the characteristic feature size

increases. For example, in grain growth, at long times the mean grain diameter

$D$ increases with time as $D \propto t^{1/2}$. Another example is coarsening

of spherical particles in a matrix; for sufficiently low volume fraction of

particles in a matrix where solute is transported by diffusion, the mean

particle radius $R$ increases with time as $R \propto t^{1/3}$.

It is also useful to be aware that the system may reach a metastable or stable

equilibrium state with respect to system energy, in which case no further

microstructural evolution will occur for increasing simulation time. In the

grain growth example, if the system evolves to a single grain, stable

equilbrium has been reached. If the system evolves to a two-grain configuration

with a flat grain boundary between the grains, it has reached a metastable

equilibrium; the system could still lower it energy by removing the grain

boundary, but in that configuration, there is no kinetic driving force to

remove it from the metastable state. To monitor for such possibilities, it is

useful for the simulation to periodically output the total free energy of the

system; a stable or metastable equilibrium state is indicated by a constant

free energy with respect to time.

## References

[1]

Biswas et al., “Solidification and grain formation in alloys: a 2D application

of the grand-potential-based phase-field approach”, Modelling and Simulation in

Materials Science and Engineering, 30 (2022) 025013. DOI:

[10.1088/1361-651X/ac46dc](https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-651X/ac46dc).

[2]

Warren et al., “Extending phase field models of solidification to

polycrystalline materials”, Acta Materialia 51 (2003) 6035–6058. DOI:

[10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00388-4](https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00388-4).

[3]

Dorr et al., “A numerical algorithm for the solution of a phase-field model of

polycrystalline materials”, Journal of Computational Physics 229 (2010)

626–641. DOI:

[10.1016/j.jcp.2009.09.041](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2009.09.041).

[4]

Ofori-Opuku et al., “A quantitative multi-phase field model of polycrystalline

alloy solidification”, Acta Materialia 58 (2010) 2155-2164. DOI:

[10.1016/j.actamat.2009.12.001](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2009.12.001)

[5]

Pusztai et al., “Phase-field approach to polycrystalline solidification

including heterogeneous and homogeneous nucleation”, Journal of Physics:

Condensed Matter 20 (2008) 404205. DOI:

[10.1088/0953-8984/20/40/404205](https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/40/404205).

Thus, it is important to evaluate the effect of orientation on the results by

misaligning the grids. Furthermore, these effects are influenced by the

discretization of the mesh. Hence, it is important to ensure that the mesh is

refined enough to properly resolve the interfaces (if necessary, run a mesh

convergence study). For more information about strategies to simulate multiple

dendrites with varying orientation, please refer to examples by Biswas et

al. [[1]](#1), Warren et al. [[2]](#2), Dorr et al. [[3]](#3), Ofori-Opoku et

al. [[4]](#4), and Pusztai et al. [[5]](#5), among others.

## Kinetics and how long to run

The amount of time the simulation should be run depends on the science or

engineering question to be answered, and on the system being studied. For many

classic phase-field problems such as grain growth and coarsening, a

characteristic feature size of the system increases with time, and the progress

of microstructural evolution slows as the characteristic feature size

increases. For example, in grain growth, at long times the mean grain diameter

$D$ increases with time as $D \propto t^{1/2}$. Another example is coarsening

of spherical particles in a matrix; for sufficiently low volume fraction of

particles in a matrix where solute is transported by diffusion, the mean

particle radius $R$ increases with time as $R \propto t^{1/3}$.

It is also useful to be aware that the system may reach a metastable or stable

equilibrium state with respect to system energy, in which case no further

microstructural evolution will occur for increasing simulation time. In the

grain growth example, if the system evolves to a single grain, stable

equilbrium has been reached. If the system evolves to a two-grain configuration

with a flat grain boundary between the grains, it has reached a metastable

equilibrium; the system could still lower it energy by removing the grain

boundary, but in that configuration, there is no kinetic driving force to

remove it from the metastable state. To monitor for such possibilities, it is

useful for the simulation to periodically output the total free energy of the

system; a stable or metastable equilibrium state is indicated by a constant

free energy with respect to time.

## References

[1]

Biswas et al., “Solidification and grain formation in alloys: a 2D application

of the grand-potential-based phase-field approach”, Modelling and Simulation in

Materials Science and Engineering, 30 (2022) 025013. DOI:

[10.1088/1361-651X/ac46dc](https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-651X/ac46dc).

[2]

Warren et al., “Extending phase field models of solidification to

polycrystalline materials”, Acta Materialia 51 (2003) 6035–6058. DOI:

[10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00388-4](https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00388-4).

[3]

Dorr et al., “A numerical algorithm for the solution of a phase-field model of

polycrystalline materials”, Journal of Computational Physics 229 (2010)

626–641. DOI:

[10.1016/j.jcp.2009.09.041](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2009.09.041).

[4]

Ofori-Opuku et al., “A quantitative multi-phase field model of polycrystalline

alloy solidification”, Acta Materialia 58 (2010) 2155-2164. DOI:

[10.1016/j.actamat.2009.12.001](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2009.12.001)

[5]

Pusztai et al., “Phase-field approach to polycrystalline solidification

including heterogeneous and homogeneous nucleation”, Journal of Physics:

Condensed Matter 20 (2008) 404205. DOI:

[10.1088/0953-8984/20/40/404205](https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/40/404205).

The time evolution of the order parameter, given by the Allen-Cahn equation,

was solved using the MOOSE framework. Details of the numerical method can be

found in [Wu _et al._ (2021)](

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927025621000963?via%3Dihub).

The simulations results of nucleus evolution are shown in the figures below:

(left) order parameter profile measured radially from the center of domain at

different evolution times; (right) radius as a function of evolution time. We

see that the seed of same starting radius $r_\circ = 7.5$ units evolves starkly

differently in 2D and 3D. While the nucleus grows in 2D, it shrinks and

dissolves in 3D.

The time evolution of the order parameter, given by the Allen-Cahn equation,

was solved using the MOOSE framework. Details of the numerical method can be

found in [Wu _et al._ (2021)](

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927025621000963?via%3Dihub).

The simulations results of nucleus evolution are shown in the figures below:

(left) order parameter profile measured radially from the center of domain at

different evolution times; (right) radius as a function of evolution time. We

see that the seed of same starting radius $r_\circ = 7.5$ units evolves starkly

differently in 2D and 3D. While the nucleus grows in 2D, it shrinks and

dissolves in 3D.

The dependence on dimensionality is further illustrated by considering cases

where the initial radius is close to the critical radius: $r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$,

$r_\circ = r_c$ and $r_\circ = 1.01 r_c$. The simulation results of radius

evolution are shown above for 2D (left) and 3D (right). As expected from the

the classical homogeneous nucleation theory, the sub-critical nucleus with

$r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$ shrinks and the super-critical nucleus with $r_\circ =

1.01 r_c$ grows.

Since the nucleus in the phase-field model is a diffuse-interface approximation

of the classical sharp interface nucleus, $r_\circ = r_c$ is fairly close to an

unstable equilibrium. Ideally, the radius would remain constant with

time. However, since the system is unstable, small numerical errors accumulate

with time, eventually leading to growth or shrinkage of the nucleus. During

initial time steps, the interface profile is expected to undergo some changes

from the starting profile due to equilibration. While the $tanh$ function is a

common choice for the initial condition of the interface, it is an exact

solution only for a planar interface, representative of a 1D scenario.

## Initial conditions

For simulations of the evolution of two or more phases, it is important to

anticipate the expected equilibrium state of the system given the initial

conditions. To do this, one needs the phase diagram as determined by the bulk

contribution of the free energy density.

For example, in simulating phase separation following spinodal decomposition,

it is common to define the initial state of the order parameter as a spatially

uniform field with an added small 'noisy' perturbation with small

amplitude. However, this order parameter must be within the spinodal region of

the phase diagram, i.e., the region where spontaneous decomposition leads to a

decrease in the free energy. Below we show two instances that demonstrate that

choosing different values for the baseline order parameter, $c_{0,\mathrm{base}}$, and

the same initial perturbation term, $\xi(\vec{r})$, for the initial conditions

of leads to different dynamics.

## Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions (BC) are required to solve for the governing equations in

all phase field simulations. In general, every field must have a defined BC at

every boundary of the system. The three most common types of boundary

conditions (BC) for phase field simulation are:

- Dirichlet BC: The value of a field is specified at the boundary. This type of

boundary condition is useful whenever we want to impose a value to an order

parameter or field at one or more boundaries. Some common examples include

setting a constant value for temperature to simulate a heat reservoir, or

setting a constant value for a solid/liquid order parameter to indicate a

fixed phase beyond the confines of the system.

- Neumann BC: The value of the spatial derivative of a field is specified at

the boundary. This type of boundary conditions is useful to specify fluxes of

fields at the boundary. For example, setting natural BC (a special case of

Neumann BC) for a field at the boundary enforces that the normal component of

gradient of that field is zero along that boundary. Therefore, if a flux for

that field is proportional to this gradient, natural BC is equivalent to

imposing zero flux at the boundary. This BC is convenient to ensure that the

field is conserved. In addition, natural BCs are useful to exploit known

symmetries in the morphology of domains: for example a spherical domain can

be simulated using a quarter (in 2D) or eighth of a system (in 3D) by placing

centering the sphere in a corner of the system and imposing natural BCs along

the boundaries that define the corner.

- Periodic BCs: The value of the field in a boundary with periodic BC matches

the value from the opposite boundary. These type of BCs are useful to

simulate periodic domains, but also to minimize boundary effects. since the

system does not interact with borders.

### Try different boundary conditions and check their impact

We used the results from Benchmark [Problem 1a](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(a)-Square-periodic)

and [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

to analyze the effect of boundary conditions. In addition, we solved for

Cahn-Hilliard dynamics under the same initial condition and simulation

parameters as problem 1 but using mixed boundary conditions, i.e., different

boundary conditions for each boundary. We compare the results for each case at

simulation time _t_ = 1000. The simulations were carried out in the PRISMS-PF

framework using a uniform square mesh with $N_x = N_y = 128$ linear elements

and a time step, $\Delta t$ = 0.005. The results are shown in the figure below.

As can be seen in the figure above, for periodic boundary boundaries the

$\alpha$ - $\beta$ domains are **continuous** on opposite sides of the

system. For no-flux boundaries, the $\alpha$ - $\beta$ interfaces are

**normal** to the boundary. For Dirichlet boundaries (bottom boundary of the

right panel), the value of _c_ is **fixed** along the boundary.

## Interface width

Phase-field modeling is a diffuse interface approach, meaning that interfaces

are represented by a smooth variation of one or more order parameters across

the interface. The width of the interface is a function of the model parameters

and the interface width is determined by model parameter choices. In some

cases, an analytical expression is available that relates interface width to

phase-field model parameters (such as free energy barrier height and gradient

energy coefficient, which also impact the interfacial energy). In other cases,

no analytical solution is available and the interface width must be

approximated or determined numerically based on parameter choices. Such details

are specific to the formulation being used.

Once the relationship between model parameters and interface width is

understood, an appropriate selection of interface width needs to be made (while

maintaining the correct interfacial energy for the system being studied). In

some cases, the interface width in the phase-field model can be chosen to match

the actual physical width of the interface being studied (such typically

sub-nanometer). However, resolving a physically realistic interface width

requires a sub-nanometer grid/mesh (grid/mesh convergence is described further

in the next section). Using a physically realistic interface width often makes

it computationally unfeasible to simulate systems large enough to be

statistically representative. Therefore, in many cases an interfacial width

that is much larger than the the physical width of an interface is used. In

these cases, a careful balance between computational efficiency and model

accuracy is needed; the interface width should be chosen to be small enough

that the physics of the system are accurately represented, while maintaining

adequate computational performance. A useful rule of thumb as a starting point

is that the interface width should be at least an order of magnitude smaller

than the smallest microstructural feature size of interest. Starting from this

guideline, simulations of microstructural evolution with varying interface

widths can be run to ensure that the choice of interface width does not affect

the simulation results. A small test problem may be useful for testing

convergence with respect to interface width; for example a shrinking circular

grain embedded in another grain may be used for testing convergence of a grain

growth model with respect to interface width, rather starting with large,

costly simulations of hundreds of grains.

## Convergence studies

### Carry out grid/mesh convergence study AFTER you have finalized your interfacial width.

As an example of a mesh convergence study, we can consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. In this problem, which models spinodal decomposition

using the Cahn-Hilliard equation, the width of the diffuse interface is 4.47,

as defined by the Cahn-Hilliard equation and physical parameters in the problem

statement. Given this interface width, we need to ensure there are a sufficient

number of grid points (for finite difference schemes) or mesh elements (for

finite element or finite volume schemes) through the diffuse interface to

adequately resolve the variation of the composition order parameter.

In [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

a square domain with dimensions $200 \times 200$ and no-flux boundary

conditions is considered. An example of a mesh convergence study for this

problem using the MOOSE framework phase-field module (a finite element code) is

described. The $200 \times 200$ domain is discretized using increasing numbers

of elements $N_x$ in the $x$ direction and $N_y$ in the $y$ direction,

maintaining $N_x = N_y$ for square elements (using linear Lagrange shape

functions). The simulations with varying numbers of elements are run until a

significant amount of microstructural evolution has occurred. We need to

increase the number of elements until the microstructure at a fixed time no

longer changes with further increases in the number of elements; at this point

the simulation is converged with respect to the mesh resolution.

The simulation initial conditions and the microstructures at $t = 10,000$ are

shown in the figure below.

The dependence on dimensionality is further illustrated by considering cases

where the initial radius is close to the critical radius: $r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$,

$r_\circ = r_c$ and $r_\circ = 1.01 r_c$. The simulation results of radius

evolution are shown above for 2D (left) and 3D (right). As expected from the

the classical homogeneous nucleation theory, the sub-critical nucleus with

$r_\circ = 0.99 r_c$ shrinks and the super-critical nucleus with $r_\circ =

1.01 r_c$ grows.

Since the nucleus in the phase-field model is a diffuse-interface approximation

of the classical sharp interface nucleus, $r_\circ = r_c$ is fairly close to an

unstable equilibrium. Ideally, the radius would remain constant with

time. However, since the system is unstable, small numerical errors accumulate

with time, eventually leading to growth or shrinkage of the nucleus. During

initial time steps, the interface profile is expected to undergo some changes

from the starting profile due to equilibration. While the $tanh$ function is a

common choice for the initial condition of the interface, it is an exact

solution only for a planar interface, representative of a 1D scenario.

## Initial conditions

For simulations of the evolution of two or more phases, it is important to

anticipate the expected equilibrium state of the system given the initial

conditions. To do this, one needs the phase diagram as determined by the bulk

contribution of the free energy density.

For example, in simulating phase separation following spinodal decomposition,

it is common to define the initial state of the order parameter as a spatially

uniform field with an added small 'noisy' perturbation with small

amplitude. However, this order parameter must be within the spinodal region of

the phase diagram, i.e., the region where spontaneous decomposition leads to a

decrease in the free energy. Below we show two instances that demonstrate that

choosing different values for the baseline order parameter, $c_{0,\mathrm{base}}$, and

the same initial perturbation term, $\xi(\vec{r})$, for the initial conditions

of leads to different dynamics.

## Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions (BC) are required to solve for the governing equations in

all phase field simulations. In general, every field must have a defined BC at

every boundary of the system. The three most common types of boundary

conditions (BC) for phase field simulation are:

- Dirichlet BC: The value of a field is specified at the boundary. This type of

boundary condition is useful whenever we want to impose a value to an order

parameter or field at one or more boundaries. Some common examples include

setting a constant value for temperature to simulate a heat reservoir, or

setting a constant value for a solid/liquid order parameter to indicate a

fixed phase beyond the confines of the system.

- Neumann BC: The value of the spatial derivative of a field is specified at

the boundary. This type of boundary conditions is useful to specify fluxes of

fields at the boundary. For example, setting natural BC (a special case of

Neumann BC) for a field at the boundary enforces that the normal component of

gradient of that field is zero along that boundary. Therefore, if a flux for

that field is proportional to this gradient, natural BC is equivalent to

imposing zero flux at the boundary. This BC is convenient to ensure that the

field is conserved. In addition, natural BCs are useful to exploit known

symmetries in the morphology of domains: for example a spherical domain can

be simulated using a quarter (in 2D) or eighth of a system (in 3D) by placing

centering the sphere in a corner of the system and imposing natural BCs along

the boundaries that define the corner.

- Periodic BCs: The value of the field in a boundary with periodic BC matches

the value from the opposite boundary. These type of BCs are useful to

simulate periodic domains, but also to minimize boundary effects. since the

system does not interact with borders.

### Try different boundary conditions and check their impact

We used the results from Benchmark [Problem 1a](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(a)-Square-periodic)

and [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

to analyze the effect of boundary conditions. In addition, we solved for

Cahn-Hilliard dynamics under the same initial condition and simulation

parameters as problem 1 but using mixed boundary conditions, i.e., different

boundary conditions for each boundary. We compare the results for each case at

simulation time _t_ = 1000. The simulations were carried out in the PRISMS-PF

framework using a uniform square mesh with $N_x = N_y = 128$ linear elements

and a time step, $\Delta t$ = 0.005. The results are shown in the figure below.

As can be seen in the figure above, for periodic boundary boundaries the

$\alpha$ - $\beta$ domains are **continuous** on opposite sides of the

system. For no-flux boundaries, the $\alpha$ - $\beta$ interfaces are

**normal** to the boundary. For Dirichlet boundaries (bottom boundary of the

right panel), the value of _c_ is **fixed** along the boundary.

## Interface width

Phase-field modeling is a diffuse interface approach, meaning that interfaces

are represented by a smooth variation of one or more order parameters across

the interface. The width of the interface is a function of the model parameters

and the interface width is determined by model parameter choices. In some

cases, an analytical expression is available that relates interface width to

phase-field model parameters (such as free energy barrier height and gradient

energy coefficient, which also impact the interfacial energy). In other cases,

no analytical solution is available and the interface width must be

approximated or determined numerically based on parameter choices. Such details

are specific to the formulation being used.

Once the relationship between model parameters and interface width is

understood, an appropriate selection of interface width needs to be made (while

maintaining the correct interfacial energy for the system being studied). In

some cases, the interface width in the phase-field model can be chosen to match

the actual physical width of the interface being studied (such typically

sub-nanometer). However, resolving a physically realistic interface width

requires a sub-nanometer grid/mesh (grid/mesh convergence is described further

in the next section). Using a physically realistic interface width often makes

it computationally unfeasible to simulate systems large enough to be

statistically representative. Therefore, in many cases an interfacial width

that is much larger than the the physical width of an interface is used. In

these cases, a careful balance between computational efficiency and model

accuracy is needed; the interface width should be chosen to be small enough

that the physics of the system are accurately represented, while maintaining

adequate computational performance. A useful rule of thumb as a starting point

is that the interface width should be at least an order of magnitude smaller

than the smallest microstructural feature size of interest. Starting from this

guideline, simulations of microstructural evolution with varying interface

widths can be run to ensure that the choice of interface width does not affect

the simulation results. A small test problem may be useful for testing

convergence with respect to interface width; for example a shrinking circular

grain embedded in another grain may be used for testing convergence of a grain

growth model with respect to interface width, rather starting with large,

costly simulations of hundreds of grains.

## Convergence studies

### Carry out grid/mesh convergence study AFTER you have finalized your interfacial width.

As an example of a mesh convergence study, we can consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. In this problem, which models spinodal decomposition

using the Cahn-Hilliard equation, the width of the diffuse interface is 4.47,

as defined by the Cahn-Hilliard equation and physical parameters in the problem

statement. Given this interface width, we need to ensure there are a sufficient

number of grid points (for finite difference schemes) or mesh elements (for

finite element or finite volume schemes) through the diffuse interface to

adequately resolve the variation of the composition order parameter.

In [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

a square domain with dimensions $200 \times 200$ and no-flux boundary

conditions is considered. An example of a mesh convergence study for this

problem using the MOOSE framework phase-field module (a finite element code) is

described. The $200 \times 200$ domain is discretized using increasing numbers

of elements $N_x$ in the $x$ direction and $N_y$ in the $y$ direction,

maintaining $N_x = N_y$ for square elements (using linear Lagrange shape

functions). The simulations with varying numbers of elements are run until a

significant amount of microstructural evolution has occurred. We need to

increase the number of elements until the microstructure at a fixed time no

longer changes with further increases in the number of elements; at this point

the simulation is converged with respect to the mesh resolution.

The simulation initial conditions and the microstructures at $t = 10,000$ are

shown in the figure below.

As the number of elements in each direction is increased from 40 to 80 to 160,

changes in the microstructure are observed. However, once the number of

elements increases to 320, no further changes are observed in the

microstructure. Therefore, the problem is converged with respect to mesh

resolution at $N_x = N_y = 160$. For this number of elements, each element has

size $\Delta x = \Delta y$ = 200 / 160 = 1.25. Therefore, the number of

elements through the diffuse interface width is 4.47 / 1.25 = 3.6. Practical

experience in the phase-field community has shown that somewhere between 3 to 5

elements through the interface are usually required to obtain mesh convergence;

however, the appropriate resolution is problem-specific, and convergence should

be tested for the specific physics and parameters at hand.

### Carry out time step convergence studies. Try higher-order schemes, adaptive time stepping, etc. For explicit time integration, know your stability limit.

For codes that use explicit time integration, there is a maximum value of the

time step beyond which the solution becomes numerically unstable. This

stability limit can be determined by the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL)

condition and, in general, it strongly depends on the order of the spatial

derivatives. Below we show the simulation results of [Benchmark Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

using time step values slightly below and slightly above the stability

limit. We employed a forward Euler time-integration scheme and spatially

discretized the system using $128 \times 128$ first order elements. The

simulations were performed in the PRISMS-PF framework. The left panel of the

figure below shows a snapshot of the concentration at time $t=33$, which was

obtained using a stable time step of $\Delta t=0.015$. If the time step is

increased to $\Delta t=0.016$, the time step goes above the stability

limit. The right panel shows the concentration at time $t \simeq 32.39$ for

$\Delta t=0.016$ and features a numerical instability that appears near the

bottom boundary. After only four time steps the amplification of this

instability caused the simulation to fail.

As the number of elements in each direction is increased from 40 to 80 to 160,

changes in the microstructure are observed. However, once the number of

elements increases to 320, no further changes are observed in the

microstructure. Therefore, the problem is converged with respect to mesh

resolution at $N_x = N_y = 160$. For this number of elements, each element has

size $\Delta x = \Delta y$ = 200 / 160 = 1.25. Therefore, the number of

elements through the diffuse interface width is 4.47 / 1.25 = 3.6. Practical

experience in the phase-field community has shown that somewhere between 3 to 5

elements through the interface are usually required to obtain mesh convergence;

however, the appropriate resolution is problem-specific, and convergence should

be tested for the specific physics and parameters at hand.

### Carry out time step convergence studies. Try higher-order schemes, adaptive time stepping, etc. For explicit time integration, know your stability limit.

For codes that use explicit time integration, there is a maximum value of the

time step beyond which the solution becomes numerically unstable. This

stability limit can be determined by the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL)

condition and, in general, it strongly depends on the order of the spatial

derivatives. Below we show the simulation results of [Benchmark Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

using time step values slightly below and slightly above the stability

limit. We employed a forward Euler time-integration scheme and spatially

discretized the system using $128 \times 128$ first order elements. The

simulations were performed in the PRISMS-PF framework. The left panel of the

figure below shows a snapshot of the concentration at time $t=33$, which was

obtained using a stable time step of $\Delta t=0.015$. If the time step is

increased to $\Delta t=0.016$, the time step goes above the stability

limit. The right panel shows the concentration at time $t \simeq 32.39$ for

$\Delta t=0.016$ and features a numerical instability that appears near the

bottom boundary. After only four time steps the amplification of this

instability caused the simulation to fail.

Codes that use implicit time stepping schemes may have fewer restrictions with

respect to stability as time step size is increased, depending on the

problem. However, discretization error still occurs in implicit schemes and

increases with the size of the time step taken. Therefore, a convergence study

should be carried out to ensure that the size of the time step does not affect

the simulation results. As an example, we can again consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. [Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

was solved with the phase-field module from the MOOSE framework using $N_x =

N_y = 160$. The results are shown below. The microstructure at $t = 1000$

remains the same for $\Delta t = 0.1$, $\Delta t = 0.25$, and $\Delta t =

0.5$. Some differences in the microstructure are observed at $\Delta t = 1$,

and further differences become apparent at $\Delta t = 4$. In practice, it is

recommended to start with a given time step and gradually decrease it until no

changes are apparent with further decreases in time step size.

Adaptive time stepping can be useful to increase the time step size during time

periods in the simulation where there are fewer microstructural changes,

particularly for codes that use implicit time stepping schemes. However,

convergence must still be checked for the parameters of the time stepping

scheme being used. An example is the IterationAdaptiveDt time stepping scheme

used in the MOOSE framework. This scheme attempts to increase or decrease the

time step to keep the solver using a certain number of nonlinear iterations

(controlled by the parameter `optimal_iterations`), within a window or plus or

minus the parameter `iteration_window`. Higher values of `optimal_iterations`

parameter result in higher time steps, and with that comes the risk of

discretization error changing simulation results. As shown in the following,

for [Problem 1b](

https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux),

`optimal_iterations` values of 6 or 8 gave results consistent with the

converged time step of 0.5, but when `optimal_iterations` was significantly

increased to 15, changes in the microstructure resulted.

## Impact of Orientation

Oftentimes, the results of the phase field simulations are sensitive to the

orientation and alignment of the key microstructural features with the

mesh/grid points. To demonstrate this we pick a simple solidification problem

with dendritic structure formation. In this case, we utilize the solidification

[example](https://github.com/idaholab/moose/blob/next/modules/phase_field/examples/anisotropic_interfaces/snow.i)

from the MOOSE-based phase field module. This example problem can quickly

demonstrate dendritic structure formation including the formation of secondary

dendritic arms in a computationally cost-effective manner. Here, we use 4-fold

symmetry of the structure and vary the reference angles to misorient the

dendritic arms with respect to the mesh. Dendritic structures corresponding to

0 and 45 degree reference angle is presented below:

Codes that use implicit time stepping schemes may have fewer restrictions with

respect to stability as time step size is increased, depending on the

problem. However, discretization error still occurs in implicit schemes and

increases with the size of the time step taken. Therefore, a convergence study

should be carried out to ensure that the size of the time step does not affect

the simulation results. As an example, we can again consider [Benchmark Problem

1](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/) from the

Phase-Field Community Hub. [Problem

1b](https://pages.nist.gov/pfhub/benchmarks/benchmark1.ipynb/#(b)-Square-no-flux)

was solved with the phase-field module from the MOOSE framework using $N_x =

N_y = 160$. The results are shown below. The microstructure at $t = 1000$

remains the same for $\Delta t = 0.1$, $\Delta t = 0.25$, and $\Delta t =

0.5$. Some differences in the microstructure are observed at $\Delta t = 1$,

and further differences become apparent at $\Delta t = 4$. In practice, it is

recommended to start with a given time step and gradually decrease it until no

changes are apparent with further decreases in time step size.

Adaptive time stepping can be useful to increase the time step size during time

periods in the simulation where there are fewer microstructural changes,

particularly for codes that use implicit time stepping schemes. However,

convergence must still be checked for the parameters of the time stepping

scheme being used. An example is the IterationAdaptiveDt time stepping scheme

used in the MOOSE framework. This scheme attempts to increase or decrease the

time step to keep the solver using a certain number of nonlinear iterations